THE GIST

In late January, the Hop Growers of America released its report on the 2017 harvest, highlighting the most productive year for the country's hop farmers in terms of pounds since the organization began compiling statistics in 2000. More than 104 million pounds were collected from the Pacific Northwest, America's main growing region, with an overall total of 106.5 million pounds from all reporting states. The yearly results are compiled with data from USDA-NASS, HGA, the International Hop Growers Convention, and other industry and government sources.

Among highlights noted by the Hop Growers of America, U.S. acreage increased nearly 80% between 2012 and 2017, and production grew by 77%. And after five consecutive years of declining average yield, the amount of hops harvested per acre also grew 14% compared to 2016 due to "maturing" hops and favorable weather conditions, according to the group.

In a release announcing the data, the organization noted that "global hop demand appears to be on the rise thanks to burgeoning international craft beer cultures," and brewers are eyeing the reverberations of a years-long shift that has made aroma hops predominant over alpha/bittering hops. The aroma to alpha ratio was 80:20 in 2017 after a near 50-50 split in 2012.

WHY IT MATTERS

To American craft beer drinkers, and increasingly those around the world, hop flavor is creating massive change in expectations of flavor and experience. Depending on point-of-sale definition, IPA makes up somewhere between a quarter to a third of craft sales in the U.S. (Note: this is Brewers Association-defined “craft” vs. IRI “craft,” which includes Goose Island, Lagunitas, and other breweries owned by national and international parent companies.) But no matter how a drinker chooses to define the beer in the glass, it’s obvious that there’s a good chance it’s hop-forward. According the Brewers Association, there are more IPA brands sold in IRI's multi-outlet and convenience retail channel universe (MULC) than the next three brands (seasonal, pale Lagers, Stout) combined.

source: Hop Growers of America

This is reflected in many ways, including the rapid increase in acres planted and the rising average cost per pound, which reached $5.92 in 2017, just a 3.5% increase from the year prior, but a 77% jump over the five-year span of 2013-2017, connected to the change from lower-priced alpha to higher-cost aroma varieties.

source: Hop Growers of America

Much of this change is led by the runaway popularity of designer hops, which have been at the core of American farmers' shift from alpha to aroma varieties. In terms of global production, it’s the U.S. vs. The World when it comes to aroma hops—America accounts for nearly half of what’s harvested, as production of alpha has dwindled.

source: International Hop Growers' Convention

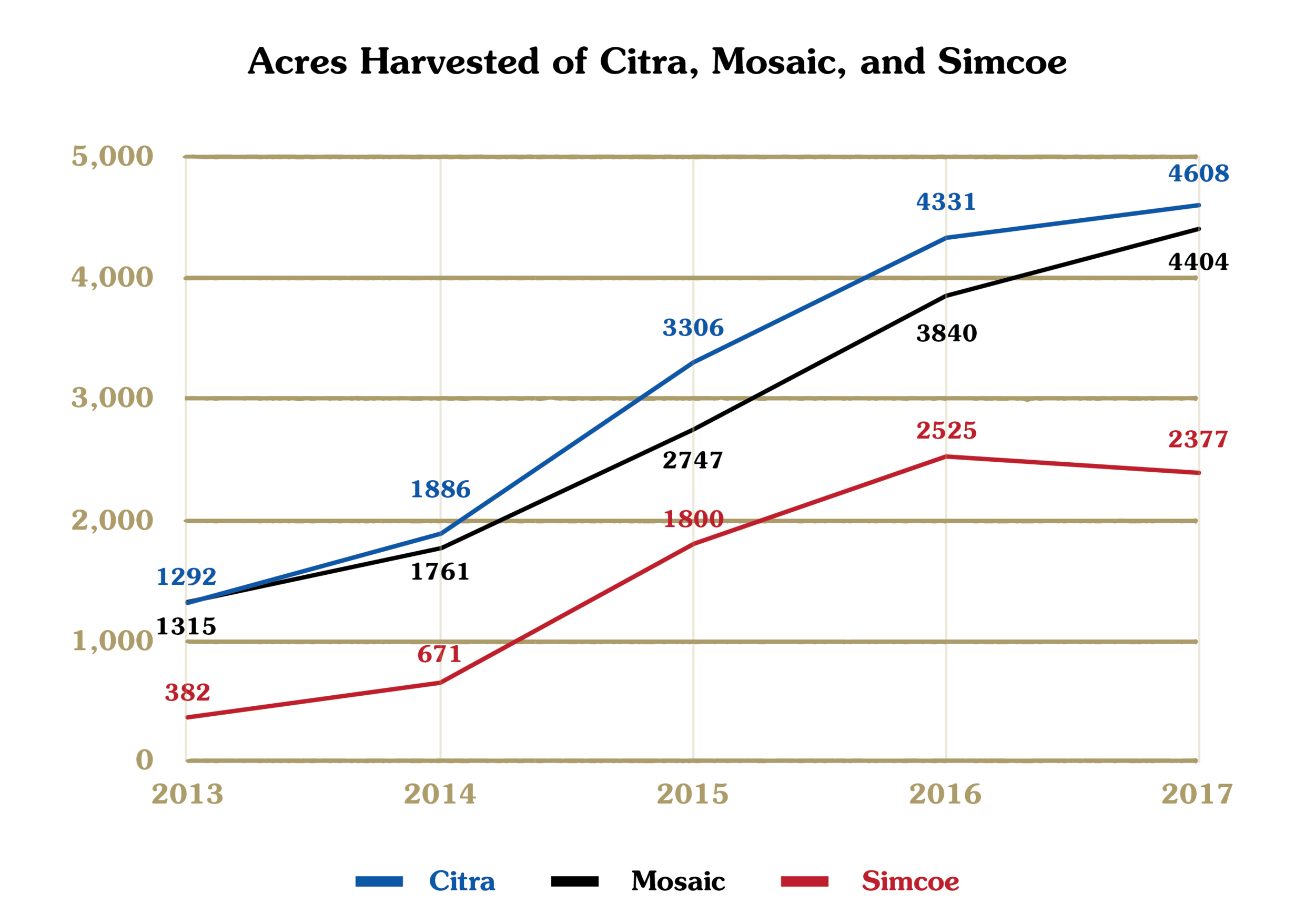

The success of aroma hops can almost be directly seen through the rise of three varieties: Citra, Mosaic, and Simcoe. But it's the first two that received considerable love from brewers in 2017. According to my analysis of "best beer" lists created for last year, Citra (28) and Mosaic (24) were easily the most-cited hops contained in the recipes of favorite beers from industry pros, writers, and other tastemakers. Simcoe was part of 12 such beer recipes in 2016, but just four in 2017, per that same review of lists.

source: Hop Growers of America

Among one of the quirkier findings from the Hop Growers of America's report is the news that, for the first time, Idaho surpassed Oregon in production to become the second-highest hop producing state. Idaho farmers gathered 13.7 million pounds of hops to Oregon's 11.9 million. Washington destroyed them both with 78.7 million.

Why? The varieties grown in Idaho were higher yielders than those grown in Oregon. In Idaho, varieties included Bravo (2,799 pounds per acre), Zeus (2,756), and Mosaic (2,581). The top three in Oregon were Super Galena (2,096 pounds per acre), Mosaic (1,875), and Nugget (1,820). Idaho had seven varieties that averaged more than 2,000 pounds per acre. Oregon only had one.

Of interest to craft beer enthusiasts may be Anheuser-Busch InBev's Elk Mountain Farm, which is located in Idaho and provides hops for Goose Island, 10 Barrel Brewing, Elysian Brewing, and other members of its High End portfolio. There are eight main varieties grown at the farm (Amarillo, Cascade, Centennial, Hallertau, Mt. Hood, Saaz, Willamette, and Northern Brewer) spread across about 1,700 acres, according to most recent reports. That means the farm accounts for about a quarter of the state’s roughly 7,000 acres.

With some thoroughly unscientific, back-of-the-napkin math, that acreage, multiplied by the averaged yield of all varieties grown in Idaho (1,968 pounds) and reported by the Hop Growers of America, would mean almost 3.4 million pounds of hops were grown for AB InBev’s brands and others in 2017 (some of Elk Mountain’s production is sold to other breweries). That harvest was about a quarter of the state’s reported overall yield.

But to put that in perspective with America’s major craft brands and their hop usage, it’s not bad. According to the Brewers Association, the average craft brewer uses 1.52 pounds of hops per barrel. This means that, by their own estimates, Boston Beer would use about 3.5 million pounds of hops a year, and Sierra Nevada and New Belgium combined would use about the same amount grown at Elk Mountain.

No matter how cute the stats can get with projections and conjecture, one thing is seriously clear: hops will continue to dominate in-industry conversations around agriculture, brewing practices, and insatiable drinker preferences. It’s a big reason why the Brewers Association is committing about $575,000 to enhance public hop breeding programs and provide all brewers the chance for new varieties that not only provide new flavors, but also stronger yields and greater protection against pest and disease.

While trends in hops are leaning toward the haze of late, the literal and figurative value of this cash crop is a pivotal part of of an ever-growing industry. That much is crystal clear.

—Bryan Roth