The Brewers Association is hoping a major investment into hop research will help launch creation of new varieties resistant to disease, widely available and with flavor traits sought after by brewers and drinkers alike.

The trade organization recently pledged about $575,000 to be spent in the remainder of 2017 and 2018 by the USDA as a way to begin work toward a new public hop breeding program. Additional support will be provided in 2019 and beyond at undecided amounts.

According to the Hop Growers of America, the BA’s investment represents a significant amount when compared to the $700,000 federal government provides to the USDA annually to cover salaries, benefits, equipment maintenance and more related to hop research. The BA’s contribution, funded through revenues like membership dues, events and merchandise sales, will provide for a full-time USDA project lead to focus on hop breeding, with potential for a second staff member to focus on genetics.

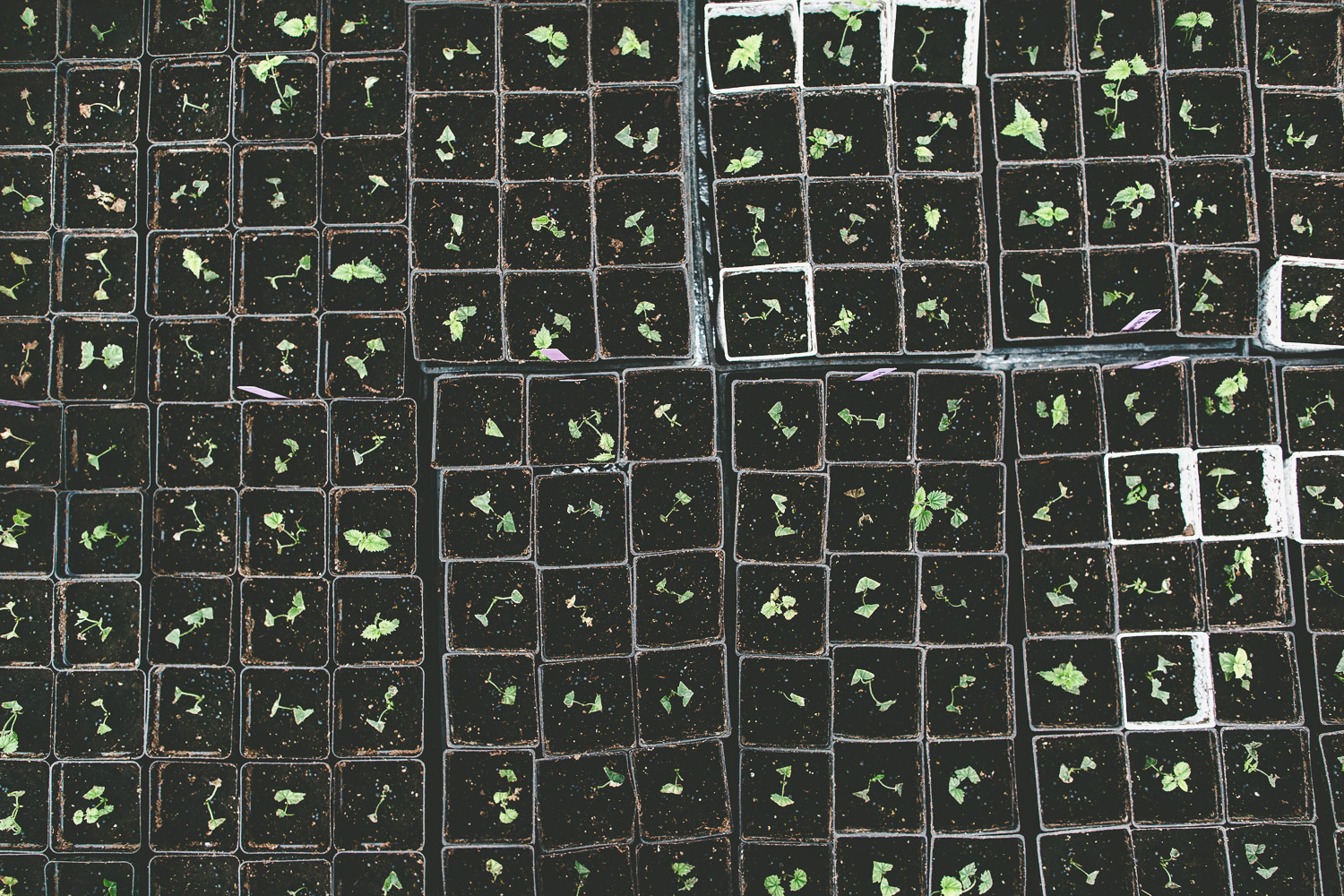

Creation of new hop breeds ready for use can take at least 10 years, but the hope is that this new partnership will eventually present a new variety that can withstand diseases like downy and powdery mildew, as well as offer yields of at least 2,000 pounds per acre. All varieties released from the program will be public and available to all farmers and breweries, with no compensation returning to the BA or USDA.

“For many years, our industry has really struggled to systematically move varieties out of the breeding pipeline into commercialized level,” says Chris Swersey, supply chain specialist for the BA. “We are essentially the stakeholder that has a tremendous duty to invest in the crop to ensure the long-term sustainability for growers and availability for our members.”

To put the investment in perspective, the Brewers Association administered 22 research grants in 2016 worth about $400,000 to cover analysis of ingredients and agricultural practices. About $500,000 was provided across 19 grants in 2017, with the hop breeding program funding a completely separate budget line.

Ryan Hayes, research leader of USDA’s Forage Seed and Cereal Research Unit in Corvallis, Oregon, said it could be the first time the USDA would have a breeder and geneticist solely dedicated to its hop research, something common for development with private companies. More in-depth work into molecular markers could make finding ideal traits faster and more efficient than a timeframe that can typically take a decade or more, he says.

“It would allow us to make decisions sooner if we want to advance one cone to use as a parent,” added Hayes, the USDA’s liaison in partnership with the Brewers Association. Along with hops brought to fruition through the program, Hayes noted tools and methods from the process would be made available through channels such as presentations, field days and peer-reviewed publications.

The move comes at a pivotal time for the American hop system. The U.S. now leads the world in total production, but it’s come at a cost: the overall average of hop yield from American farms has been on the decline over the past decade while prices have essentially doubled. Since an average yield of 2,383 pounds per acre in 2009, the figure has crept slowly downward, decreasing 24% to an estimated 1,803 for 2017's crop due to popularity of aroma varieties that produce lower yields. Based on a conservative estimate of price increases for hops over the last two years, 2017's average cost should eclipse $6 a pound, a jump of at least 70% over the same timespan.

Demand isn't going anywhere. Swersey says the average hop useage for craft brewers is 1.52 pounds per barrel, and based on 2016 production levels, that means Brewers Association-defined “craft” breweries used about 36.1 million pounds of hops last year. That’s equivalent to 41.5% of all the hops grown in the Pacific Northwest, although U.S. brewers commonly use hops from all over the world.

Most important to the BA-USDA project is the shift in recent years of what and how those hops have been used. Until 2013, high alpha hops (typically used for bittering) took up the majority of acreage in the U.S. As brewer and drinker preferences have changed toward different hop-forward experiences in beer (“juicy” comes to mind…) aroma hops flipped the script. In 2016, the ratio of aroma (78%) to high alpha (22%) acres was almost four-to-one because aroma hops yield fewer pounds per acre and need more land to fulfill demand.

Of the top-10 aroma hops planted for 2017, five resulted from public research with the other half coming from private companies, which can restrict use among farmers.

While the total amount of acres is split fairly evenly among these aroma varieties (publicly-available Cascade and Centennial are a big reason for that) the change in 2016 harvested acres to 2017 acres strung for harvest favor registered or trademarked options. According to figures from an annual report compiled by the Barth-Haas Group, private varieties among the top-10 strung aroma hops received about 1,750 more acres for 2017 while public ones increased by roughly 570.

The numbers don’t lie. In terms of use and advancement of public hops, the investment from the Brewers Association will be valuable literally and figuratively. In order to provide more cost efficient and readily available hops, it was an ideal time to step in with investment.

“Every year, we do a hop survey for our members and we know that aroma varieties are the ones they cherish,” says Swersey. “We need to focus on aroma varieties that are disease and pest resistant, but also will be competitive in yield to get attention from growers.”

In coordination with creating new USDA-supervised positions, the Brewers Association will support technical research with sensory efforts as part of the project. Swersey noted a new hop assessment program will launch in 2018 that will eventually include hundreds of brewers who can provide feedback on experimental hop varieties. Polling this group will push USDA research toward particular flavors or traits. Priority will be placed on new varieties already eight to 10 years in development to expedite potential availability to brewer. Aspects like yield, “pickability” and disease resistance will be important in consideration, Swersey says.

In the near term, Hayes and Swersey are working to hire new USDA staff and locate a site for research in Washington. In a post on the Brewers Association's website, Swersey says the "horizon for success" could be 10 to 15 years.

“We’re not expecting immediate results here,” he tells GBH. “This is a forward looking, strategic investment to make sure that we don’t get far down the road and wonder what happened to our pipeline of varieties.”

— Bryan Roth