THE GIST

With hopes of increasing its influence across a range of sectors in Washington D.C., Amazon has spent heavily on its lobbying efforts in recent years, doling out about $44 million from 2015–2018.

But this week it was revealed the company is now turning its attention to alcohol, adding to its fast-growing stable of lobbyists, which has doubled to almost 30 since the 2016 election. Amazon’s newest addition to its collection of public policy "managers" will, according to the job posting for the position, "help lead state and local engagement and public policy activities" related to alcohol regulation. The candidate will also:

“Ensure policymaker awareness of Amazon’s beer, wine and spirits business models.”

“Effect change and drive policymaking that benefits our customers.”

“Manage and coordinate external advocacy efforts, outreach programs, and initiatives in concert with business objectives.”

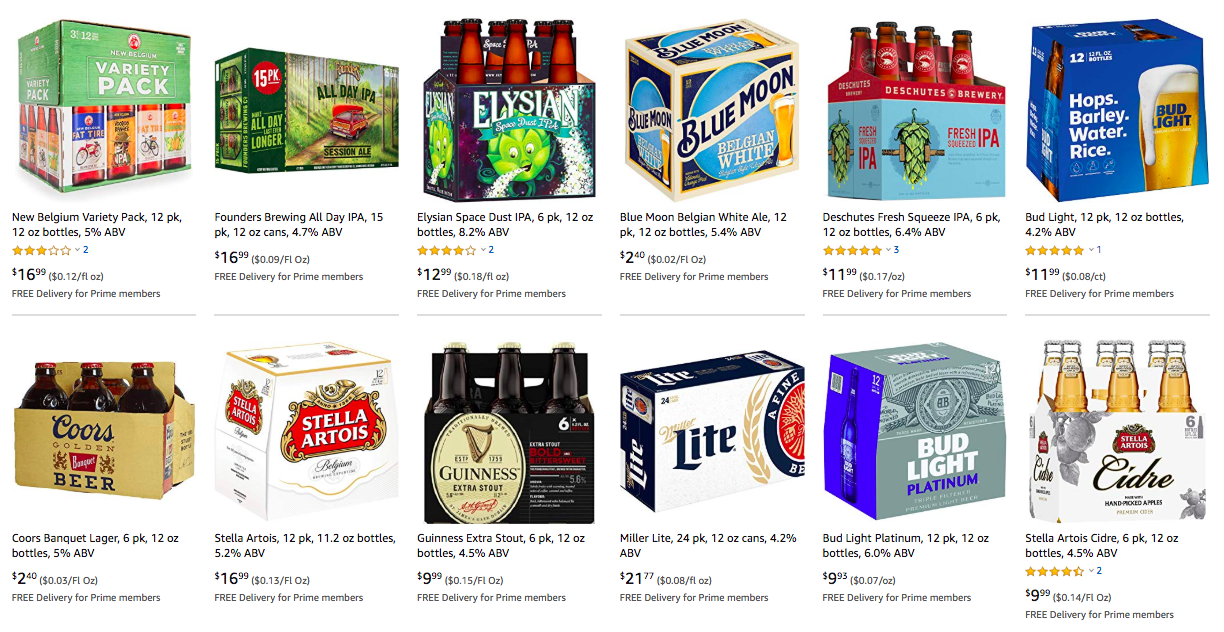

As Amazon has become more ubiquitous in Americans’ lives—it has around 101 million Prime subscribers, the equivalent of more than a third of all U.S. adults—its presence in Washington has steadily grown. However, a focus on alcohol is relatively new, and accompanies the company’s slow expansion into a pseudo-distributor. About 30 major cities can receive wine delivery, and around half that eligible for wine, beer, and spirits.

Amazon declined to respond to the Washington Business Journal, which first announced the position (h/t to Beer Business Daily). The paper also paraphrased Rabobank International beverage sector strategist Stephen Rannekleiv, who noted that this could be a move to “completely change the regulatory game for alcohol shipment.”

"I would guess they would like to influence public policy and eventually get to the point where they can ship wine to any consumer in the country," Rannekleiv told the outlet.

The online retailer had previously tried—and failed—with Amazon Wine, which functioned as a broker that allowed wineries to sell directly to customers through Amazon, and to take advantage of the company’s logistics and delivery services. According to Larry Cormier, general manager at ShipCompliant by Sovos, which worked with Amazon Wine, the effort never took off because of regulatory challenges, as noted in the Business Journal.

"I’m guessing [Amazon] is going to be lobbying the states and federal government to simplify the rules," Cormier told the paper. "I'm guessing they want to have their cake and eat it too."

WHY IT MATTERS

It was going to happen eventually, right? Amazon can’t let Pizza Hut or Buffalo Wild Wings have all the fun. Or money. But even in the early stages of recruiting, this new move by Amazon signals the potential to further disrupt a tier of alcohol already in a bit of disarray. As wholesalers continue to consolidate and work to find efficiencies, the door has swung wide open for a company like Amazon to cause chaos. Thanks to its already sizable lobbying team and deep pockets, Amazon is at least set up to bend the ears of decision-makers.

They’re doing so at the perfect time, too. According to one estimate, retailers that focus on e-commerce “are poised to gain significant market share in the home delivery of beer and wine to consumers.” Rabobank wrote in a report last year that online grocery shopping “will develop into the most important driver of online alcohol sales.” Unsurprisingly, Amazon is the leader in the online grocery space as well, selling about $3 billion in those items annually.

Not only is there an expectation that online grocery sales will move from about 3% today to 14% by 2025, but interest in online alcohol sales is also skyrocketing. “The Google data suggest that the share of alcohol sales coming online (currently 1.6%) will eventually catch up to, or even surpass, grocery overall,” Rabobank reported.

If Amazon is already “changing the buying and delivery patterns of nearly every sector of consumer goods,” it was only a matter of time before the company came for booze, says Kimberly Clements, co-founder of Pints LLC, a consulting company that helps brewers strategize new markets and distribution, and a longtime industry and distribution professional.

However, because alcohol isn’t like the other goods Amazon deals in—from vacuum cleaners to toilet paper—the necessity to “persuade and inform” politicians as outlined in the job listing will be of particular importance.

“Because if Amazon persuades and informs the right people, it can open up an entirely new world on how beer is sold and delivered to consumers,” says Clements, noting that chains like Kroger and Winn Dixie should be particularly concerned, because they deal with different models of sale in different parts of the country. What those sweeping changes might be isn’t clear at this point in time, but Amazon could likely lobby state and federal lawmakers to allow them to deliver to any and all locations. “Amazon delivers pretty much everywhere. Even to the most rural locations on a dirt road in the middle of nowhere where there may not be anyone with a liquor license for miles and miles away.”

Could those legal updates become a short-term reality? Probably not, as political efforts are often about the long game. But given the slow modernization of laws in places like Texas, Florida, or Louisiana, blowing through longstanding laws may sound fun, but it’s hard to ignore the considerable political power distributors already wield. That’s at least one reason online retail in the alcohol space has lagged behind other consumer products.

The power of alcohol delivery really became evident a few years ago, when companies like Drizly, Hopsy, and more saw business explode. Last year Drizly, arguably the category leader in alcohol delivery, raised $34.5 million in funding, more than double the amount it had previously raised up to that point. It’s the latest chapter in the ever-evolving story of alcohol distribution, where change is coming fast for beer specifically, forcing companies across the country to adapt.

It’s a weakness already identified by ZX Ventures, the disruptive investment arm for Anheuser-Busch InBev. In an interview this month with Retail Touch Points, the group’s head of e-commerce, Carolyn Brown, said that AB InBev is working with retailers like Walmart, Kroger, Drizly, and more—including Amazon—to better understand online shoppers and “share those insights with retailers and help them drive the beer category more.”

She told the publication that there’s an expectation to see online sales of beer double every year, noting that “it could come to be 10% to 20% of total beer sales in the U.S., as well as a massive piece of online grocery sales.”

Clearly, online alcohol sales are no small piece of a shrinking overall pie for booze. With shifts in consumption and category preference, aspects of convenience add up, and there’s bound to be sweeping interest in a company with logistical expertise like Amazon.

“Brewers also want to be able to sell their beer to as many people as possible,” Clements tells GBH. “Believe me, some would love to circumvent the distributor altogether and sell it directly to Amazon to handle the transaction.”

Or, maybe Amazon could just handle the entirety of the transaction itself. While it would need to jump through considerable legal hoops, Whole Foods, Amazon’s subsidiary company, has been making its own beer since 2016. Starting out as a contracted brand called Rumble Seat Beer Project, it’s now Whole Foods Market Brewing Company, based out of Houston.

In a perfect scenario for the two mega-companies, Whole Foods’ DL Double IPA, Hop Explorer IPA, or Post Oak Pale Ale would wind up on Amazon. Those brands would be sent all over the country, and would benefit from one of the best delivery services around. Consumers, meanwhile, could take advantage of some of the lowest beer prices around—which seem to be already appearing on the site for some Amazon shoppers. This is all speculation and hypothetical, of course, but if things are going to change, it starts with a march toward the capital.