With all the talk in recent years about the power and popularity of own-premise sales, it’s sometimes easy to forget just how much beer travels. According to the National Beer Wholesalers Association, more than 2.9 billion cases of beer were shipped in 2017. That could be anything from moving beer within the city it’s brewed to across a region or the country. So while more businesses see selling product at their own register as a pivotal option, there’s still a massive network moving beer all over that doesn’t just account for the biggest beer brands in America.

And like so many other industries in the country, beer could soon face a challenge when it comes to getting brands from point A to B.

“There’s always a review for supply chain and products, especially as challenges have been a little more about focus on footprint,” says Sujit Srinivas, senior director of supply chain with Portland, Oregon-based Craft Brew Alliance (CBA). “The industry is evolving at lightning pace, and what’s true yesterday isn’t true today and won’t be true tomorrow.”

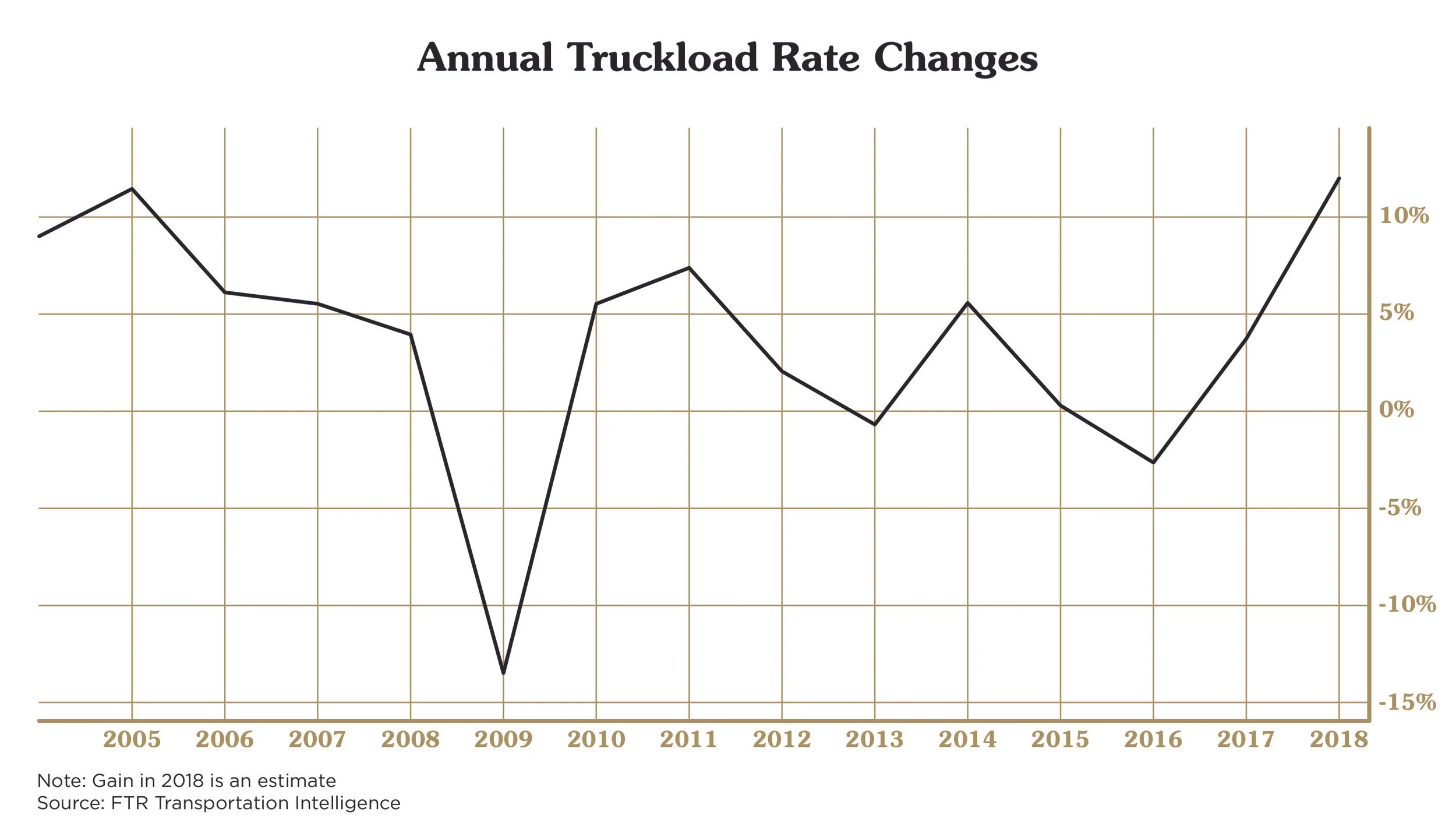

For some in beer, it could be as similar and scary a reality as it is for many others who rely on trucking. Freight costs are increasing, fewer drivers are on the road and, according to FTR Transportation Intelligence, America has a shortage of about 280,000 fewer truck drivers than it actually needs. That’s up from nearly 80,000 in 2016. The American Trucking Associations has a more conservative estimate, noting a shortage of 51,000 truck drivers nationwide at a time when 95% of trucks around the country are in use.

The impact is real for all sectors, creating late deliveries and higher costs, including for breweries. Brewbound reported that Deschutes has had trouble shipping beer during winters. Anheuser-Busch, meanwhile, citing a need to be more efficient in operations, has ordered 40 Tesla semi-trucks equipped with autonomous driving capability. Constellation Brands recently reported that increased trucking and logistics costs negatively impacted the company. And Holly Pixler, senior director of transportation and logistics for MillerCoors, recently told the company's blog that there are 10 truckloads for every one driver.

“If I can’t secure a driver to go to a site, I’m literally not going to be able to deliver beer,” she said. “We haven’t gotten to that point yet, but it’s something every shipper is concerned about right now.”

First compiled by Bloomberg

Beer companies aren’t scrambling quite yet, but it’s at least on the minds of staff like Srinivas. He says he now has double the conversations with transport companies to best determine available routes, timing, and cost. According to Srinivas and his colleague, Terry Wright, senior manager of logistics, one of the biggest challenges for shipping CBA beer is a combination of cost, optimization, and availability. The Midwest and Southeast have proven to be particularly difficult, due to proximity of stops and short mile routes.

“What you have to do is look at multiple stops and say, ‘How many miles is it? What are receiving hours of each stop? Can these stops be offloaded in the same day?’” Wright explains. On top of that, trucks need to be temperature-controlled and drivers need to be experienced enough to ensure proper handling of beer at stops.

First compiled by Bloomberg

But most of all, the future issues of delivering beer comes back to the driver shortage and new regulations limiting time truckers can be on the road, both which impact routes and cost.

Enforcement over the necessary use of electronic logging devices began this spring, which sets a cap of 11 hours for drivers to be on the road before taking a mandatory 10-hour rest. Previously, truckers could keep a manually-tracked book of hours, which could potentially allow for some fudging of numbers to ensure on-time deliveries while maintaining ideal driving times.

The equipment is attached directly into the vehicle’s electronic system to be monitored during routine inspections and has the ability to alert an owner, who could be fined as much as about $1,200 a day for violations. In turn, one survey found that almost 70% of truckers earned less money and 65% drove fewer miles. So far in 2018, about $150 million has been sought in fines.

“I’ve broken every rule known to humanity in the past to get things done and I’ve always done a good job,” says Jack Coastal, a 50-year trucking veteran and owner of Coastal Express Transport and Mountain Express, the latter of which exclusively transports beer to six states for Asheville, North Carolina’s Highland Brewing. He emphasized that breaking rules wasn’t in recent years and didn’t apply to Highland. “Five hundred miles overnight for ‘just in time’ delivery—you can’t do that stuff anymore. Those days of trucking are over with.”

Beer, Coastal says, is now one of the more desirable items for trucking companies because, aside from refrigeration, the product itself is ideal to transport. It comes on pallets, is easy to handle and is one pickup, one drop-off. “People are falling over themselves to get beer hauls,” he adds. The only challenge comes from the logging devices, which make a “short” back-and-forth trip for his company from Asheville to Raleigh a calculated time crunch that, at times, has left mere minutes before a driver would be required to end their daily hours.

Beer may be attractive, but that doesn’t mean it won’t suffer from the same issue facing other industries if trucking companies don’t see the financial incentive to move it. If CBA wanted to send beer on a three-state trip from Ohio to West Virginia and Virginia, the challenge becomes working with a trucking company for which 500 miles over three days is worth their time, especially when longer hauls earn more. Because of the electronic logging device, multiple stops over a distance of 550 miles or less increases complexity and risk of delaying trucks at stops while hours tick away, Wright says.

In some cases, the CBA team has had to collaborate with carriers to go step-by-step through a route to pinpoint hours of operations and timely unloading options. Some carriers might decline a load because they only one one-stop options, Wright notes, not realizing with the right “optimization of stops, rates and fees, the load actually does work for the carrier.”

“Five hundred to 700 miles are challenging routes because those end up turning into two or three-day transits, and if you can’t get 500 to 600 miles on a truck six days a week, it’s hard to operate at a profit,” Wright says. “The first thing we always do is try to work with our current carrier base because it doesn’t benefit us to go to the spot market.”

There are plenty of regional carriers, Wright adds, but customer service and equipment quality varies, not to mention many will only do certain areas, like Cincinnati to Wisconsin.

“I don’t think there’s negotiating any more,” Coastal says of a company’s ability to find cost-efficient transport. “Trucking is a cut throat operation all the way around.”

In a recent interview with Bloomberg, Cliff Finkle, vice president of New Jersey’s Finkle Trucking, intimated as much. “Carriers are now starting to score shippers and receivers, and the primary way of keeping score is money,” he told the outlet. “I’m just going to say, "Your place sucks, and if you really want me to go in there, I want an extra $300.”"

As so many things do in business, relationships and future success is connected to money. It’s tied back to the issue around driver recruitment, posing challenges for companies that trickle back to breweries. According to Bureau of Labor Statistics and industry research, the average age of drivers is somewhere between 49 and 55 and has increased by about three years since 2013. In a recent email sent to its customers, Tennessee-based Covenant Transport Services noted that hourly wages of $15 to $20 "is not enough to train, employ and retain top-level driving professionals" and that temperature-controlled transport faces the toughest challenge, “burdened with wasted hours at both shippers and receivers.” An issue that would easily impact coldchain aspirations of brewers.

“As a result, drivers are on the clock longer and their driving times are negatively impacted,” wrote David Parker, CEO and chairman, and Tyson Wimberly, senior vice president of sales, “Many of our professional drivers are voicing concerns about reduced productivity and pay. We have already increased driver pay in this segment by 15% this year.”

Coastal says his youngest drivers are between 55 and 60 and that he typically looks to hire staff 45 and up because they’re more experienced and dependable.

“There are new people coming in who can’t or aren’t qualified to do it,” says Wright, noting a tough situation for beer companies that ship this way: carriers have to pay more to retain employees, so per-mile costs are increasing as companies focus more on longer-distance rides to make it worth their while.

The movement of beer across states and the country will always be a part of the beer business, but increased attention on own-premise sales by breweries is a small, but fortuitous, change in model that can help some avoid an increasingly problematic challenge. That itself may make things more competitive among trucking companies looking to get into the beer business, depending on who’s left, and what companies breweries may trust. Two things that may be dwindling.

“I’ve loved this job for 50 years, but every day there are times I hate it,” Coastal says. “The obstacles of non-availability of quality drivers and government intervention are things I detest.”

“I can easily last five more years,” he adds. “Then I can hang it up.”

—Bryan Roth