Its name likely never inspired much conversation among drinkers, but over a 10-year period, Metalcraft Fabrication in Portland, OR played a significant role in growing the American craft brewing industry. Proof of that can be found today, as its custom-made tanks, fermenters, and kettles occupy brewery spaces all over the country. So this past March, it was a shock to many when, just three years removed from a major expansion of its own, Metalcraft abruptly shuttered, laying off 35 employees in the process.

It’s a sad story. It’s also a story that doesn’t end at Metalcraft. Before closing, founder Charlie Frye says the company had 17 unfinished projects in the air, for which it had received approximately $700,000 in down payments (though affected businesses believe that’s a conservative figure). And brewers aren’t expecting to see that money again, never mind the equipment it was supposed to buy. In turn, the closure of Metalcraft has caused considerable financial damage to the industry it supported for a decade, leaving those burned suspicious that the company knew more about the grimness of its situation than it claims.

As for why Metalcraft shut down, Frye says he’s unable to tell the whole story for legal reasons, but did offer a general explanation: he says the company was done in by a combination of “increased debt load as a result of our expansion” and “lessened cash flow due to fewer orders, and fewer profitable orders,” all exacerbated by “internal issues” related to bookkeeping he was unable to elaborate on.

He says he knew the company was struggling but didn’t realize it was about to flat line until late February when its bank exercised a right of offset and seized $200,000 from the company’s checking account.

“That’s when we had to just shut down immediately,” he says.

The suddenness of it all has bred suspicion among spurned brewers. Those that spoke with GBH say in the month or so leading up to its closure that they didn’t know anything was amiss, but that Metalcraft had been pushing hard for additional deposits.

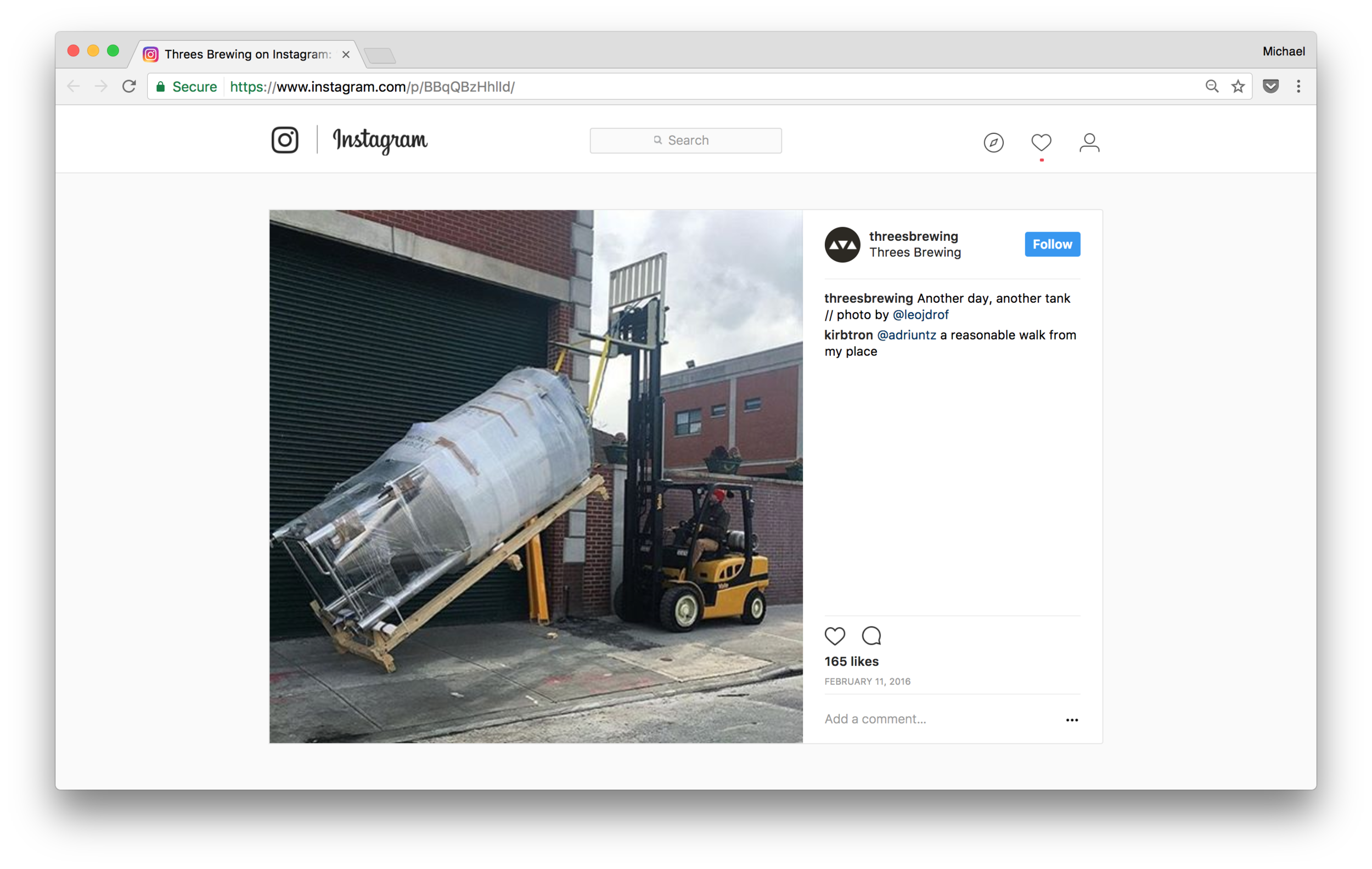

“In hindsight, I think that should’ve probably raised red flags to everyone,” says Greg Doroski, co-founder of Threes Brewing in Brooklyn, New York, one of the companies caught up in Metalcraft’s wake. “But at least at that point, none of us were really talking about it with each other.”

Because Metalcraft seemed to unravel so fast and without warning, those brewers now believe that Metalcraft actually knew the end was in sight—despite Frye’s insistence to the contrary—and withheld that information from customers.

“At what point," says one brewer who spoke to GBH on condition of anonymity, "are these people maliciously going after breweries and really engaging in explicit, overt fraud, asking them for payments when they know that they’re going out of business?”

That sentiment was echoed by other brewers with whom we spoke. But Frye says that wasn’t at all the case.

“The thing is, we did not know we were going out of business,” he says. “[The bank was] willing to work with us and consult with us towards the end in helping us put together a proposal to present to investors... We had no indication we were going out of business until days before we did.”

Regardless, the fallout is the same. In some cases, the consequences are tangible. We can’t confirm the exact amount of cash lost: Frye says “around $700,000,” but the breweries we spoke with estimated it could be as much as $2 million, basing their math off conversations they’ve had with other affected breweries. Some companies tell GBH, though they lost as little—comparatively speaking—as $20,000 while others say they are out six figures.

Four Noses of Broomfield, Colorado considers itself lucky knowing the holes from which other brewers must now crawl out. But even still, that smaller sum of lost cash has set the company’s own expansion efforts back some.

“That’s a lot of working capital to just kind of go up in smoke,” says company president and brewmaster Tommy Bibliowicz. “We definitely had relied on that for some equipment purchases that would have helped us improve processes and become more efficient, and those are pushed back another six months or so. That definitely impacted our employees and our business.”

The damage caused by the closure isn’t merely financial, though. The episode has rattled some brewers’ faith in the trustworthy nature of the industry at large. They say they accepted the fact that Metalcraft had a good reputation, having worked with renowned breweries in the past, and figured the partnership was a safe bet.

Adds Bibliowicz, now with the benefit of hindsight, “These guys are not your friends. They’re your business partners.”

Four Noses wasn’t the only company to learn this the hard way, though. Bill Baburek, owner of Infusion Brewing in Omaha, Nebraska, says this episode has changed the way his company will do business in the future.

“I’m just going to deal with people I know from now on,” he says. “I’m not going to screw around with somebody I don’t know from half way across the country. [The new manufacturers we’ve partnered with] are in Lincoln. I can keep tabs on them, I know what they’re doing.”

As for Frye, he says he empathizes with the breweries and understands both their anger and suspicions. He maintains, however, that everything at Metalcraft was on the up and up and that he is looking forward to telling the complete story when he’s legally able to do so. He says he also wants more than anything to make his former customers whole. To that end, he hopes to launch a charitable crowdfunding campaign to raise money for the affected breweries.

“I have every intention of making this right to the best of my ability,” Frye says. “I certainly have nothing to hide. I plan to share the complete story once I can do so, once it makes sense for me legally.”

Breweries, meanwhile, seem ready to learn from the ordeal and become better for it. Says Josh Stylman, co-founder at Threes in Brooklyn:

“We’re gonna work through this. It’s a bump in the road.”

—Dave Eisenberg