There’s been no shortage of outrage, both sincere and of the faux-internet-variety, in the craft beer community lately. And one of the flashpoints continues to be beer labels that cross the line from humor into racism, sexism, or simply bad taste. Even journalists seem to enjoy jumping into the fray with clickbait headlines that incite our advertising-revenue-generating rage. At GBH, we think there’s real value in a community that expresses itself like craft drinkers do, calling for brewers and bars to elevate our shared culture rather than recede into the bikini-clad beer marketing of old. But let’s talk about why this might be happening with a new, supposedly more sophisticated generation of brewers, and see if we can’t find a way forward that’s not about finger-pointing and headlines, and more about bridge building.

Beer has a bawdy past. And it wasn’t Budweiser, Miller, or even the youthful indiscretions of today’s craft brewers that invented it. Since beer has been sold, it’s been branded with the image of women, exploited in order to draw attention to a product when its own “attributes” were insufficient or boring by comparison. Which might be why you so often see this tactic employed in the marketing of Blonde Ales and Lagers—which, while they may be delicious, don’t always capture the imagination of their intended audiences as easily as another IPA. It’s a lazy approach to finding an edge. So lazy, in fact, that nearly every brewer making a Blonde Ale comes up with the same tired idea of using a busty blonde woman to complete the metaphor for audiences that might not "get it" on their own.

All this to say, when a brewer these days employs this kind of crass marketing, which has long been deemed sexist by our evolving society’s standards, they barely sense it. It’s historic, and it’s hard to see historical prejudice and exploitation with clear eyes unless someone shines a new light on it.

All press is good press, right? That’s what many think when they find themselves in the midst of an unexpected controversy. It’s a natural rationalization of a shitstorm over which you have no control. When thousands of people across the country are talking about your brand, it’s hard to see that as a failure, regardless of the topic of conversation. But that’s also the mentality of people who think that attention matters quantitatively more than qualitatively. A few million “impressions,” as SEO experts and PR agencies call it when a person simply sees your logo or name, are far less important than the lasting emotional impression you make when your brand is associated with being an asshole.

This is a short-term vs. long-term thing. Sure, you might suddenly have the whole craft beer industry paying attention to you for your ignorance, but that’s not how beer moves off a shelf. We have so many options for nearly every style of beer these days, why am I going to opt for the one made by a bunch of sexist or racist dorks? That’s not how beer sells. That’s how it gathers dust.

In your home market, people know who the brewer is, they know that brewer's personality and whether they’re a good person who made a mistake, or a person with a pattern of misogyny and racism. Far from home, half a country away, you don’t get to stand next to your sexist beer label and explain how you’re “actually a good guy” and that it’s “just a joke.” That beer has to speak for itself, and will likely say things you never expected on your behalf.

There’s no singular view of a woman's reaction to such things, of course—51% of the population doesn’t share a brain. But that brings up a bigger point—you’re likely not just offending women. I often hear people say, “Don't upset half your market with sexist jokes.” And the response is usually something like, “But I know women who thought it was funny!” The problem isn’t whether women find something funny or not. This issue is whether anyone who gets annoyed or turned off by frat-boy, basement-dwelling, sophomoric humor is willing to be associated with your brand. Chances are, the people who think you’re funny might not be the people you’d want to associate with in public. It’s a classic case of wanting to avoid a club that would have you as a member.

In the bigger picture, there are countless women who are interested in working in craft beer—as brewers, sales people, marketers, and the many other roles that need to be filled at these companies. When you make tasteless jokes and exploit images of women to sell beer, you send a clear signal about the kind of working environment you're creating for women on a daily basis.

But I guess that's not all bad. As Patton Oswalt said in a recent interview with Salon.com, "I don’t want any voices silenced, no matter how repellent, no matter how racist or homophobic. I want to hear them. I don’t like this policing of language so racists, homophobes and misogynists just think of more clever and obscure ways to get their hatred out there."

Or, put another way: when beer brands pull this kind of weak shit, it's easy enough for all of us to stop giving them our money.

These are more rare, and lack the historical context of female exploitation in beer. It’s a disturbing new trend and it’s hard to understand where it comes from exactly. But if you consider the largely white, male constitution of craft-brewery owners, it’s at least understandable how it might get out the door without much critical thought. Brewers are also using more unique ingredients and blending styles than ever before, so they’re often pulling visual and name inspiration from other cultures as a way of explaining the beer’s flavors or ingredients. This is a logical starting place, but it’s so easy to mistake inspiration with exploitation and cultural appropriation. Italians don’t even like it when we call a domestic product "parmesan cheese." You think immigrants or minorities in your market are going to think it’s funny when they see you making a joke about their cultures in order to sell some beer?

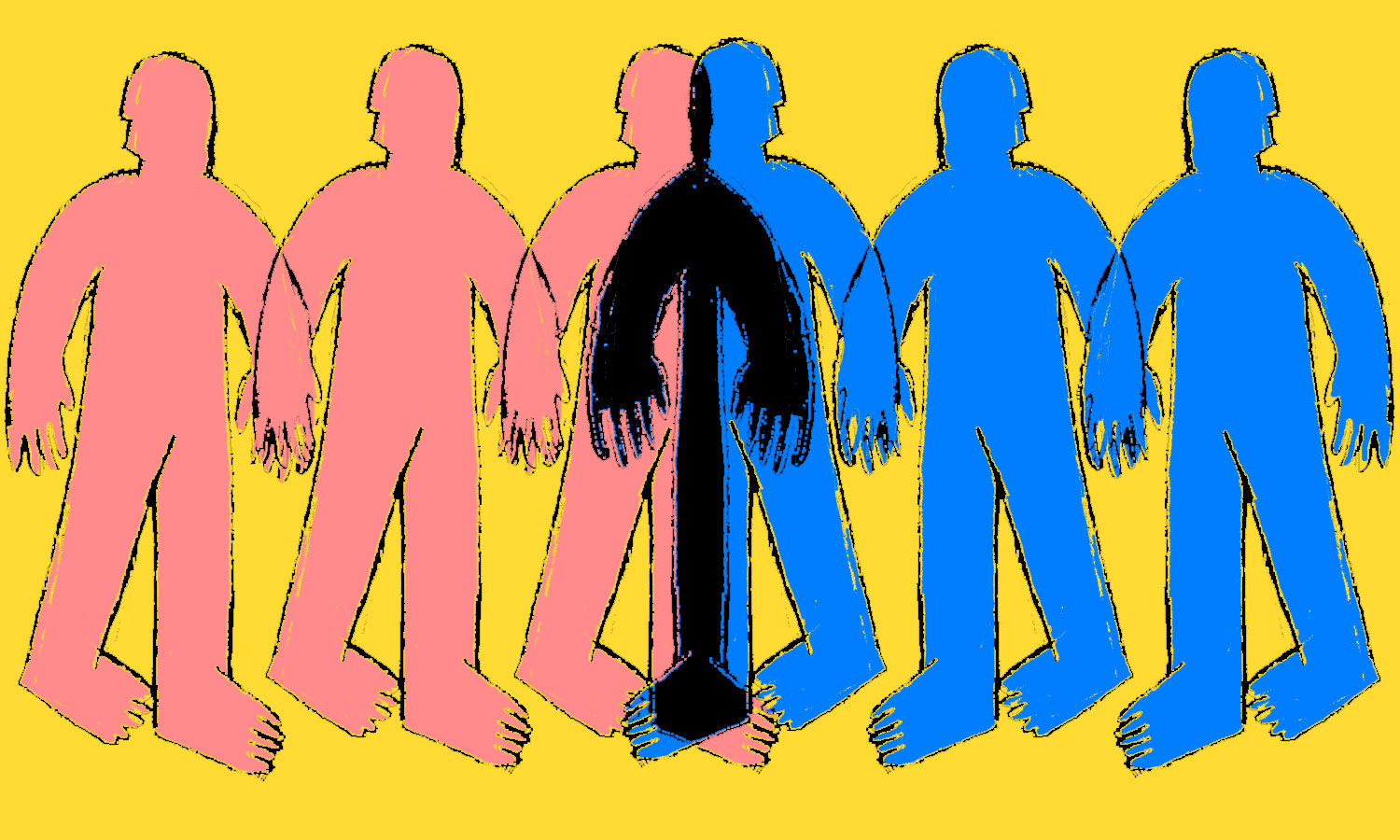

One culture’s joke is the oppression of another, and those in power often aren’t motivated to care. While craft beer’s audiences are quickly diversifying in both gender and race, it remains significantly skewed toward caucasian and male. So what we have are these white guys telling jokes to other white guys through beer. Any criticism they hear as a result is coming from a voice that feels outside their perceived community. And that’s the real a-ha here. As craft beer quickly diversifies, there’s a real, meaningful gap in cultural awareness and empathy being exposed.

Craft brewers usually start small, very small, making beer and developing a brand for an also-very-small audience made up of family, friends, and neighbors. If your immediate community is a mono-culture, you’re ill-equipped when the time comes to grow and sell your beer to a wider market. That could mean you make mistakes in pricing and format if you don’t understand a new city or region. But in some cases, it also means that your brand gets exposed for the Neanderthal it is. It might be as simple as a logo or imagery that looks out-dated and hokey. But it might mean that the jokes you were telling your friends are actually homophobic, sexist, or racist.

Small brewers never expected to find themselves on a national stage, and the internet certainly has a powerful affect on these small businesses, for better and worse. The craft beer community that uses social media to gain knowledge, find new beers, and share them with their friends can elevate your small operation overnight. But they can also crush you. It’s as true for a tiny brewery with a racist label as it is for operations like Lagunitas who withdraw trademark lawsuits in the face of that power. Every brewery starting up today should take a long look in the mirror and ask themselves what people on the other side of the country would think of them. How would they interpret my voice? How would communities outside my friends and family react to my brands? If you don’t have an internal gauge, then ask people with a different worldview, a different life experience. It’s okay to make mistakes. It’s not okay to be indifferent.

If, in the end, you decide to move forward with a bad idea, only the market can correct you. And it will.

Taking to our digital airwaves is certainly effective in bringing something to a brewer’s attention. They see it, they get nervous. But it might not create the change we want. We all know that if we’re shamed, and our back is against the wall, we tend to fight back and defend ourselves rather than listen and grow from the criticism. Internet outrage is starting to look like the bully in this context, regulating speech and shaming others for what they perceive as a simple misunderstanding.

If we’re the bullies, then we can unwittingly make the offender the hero—fighting for free speech or some twisted idea of it. They’re dead wrong about that, of course, but that doesn’t change the emotional reality of the situation. And if changing their perception and actions is your end-goal, you’re going to have to take the high road here.

More effective are even-handed, personal interactions that come from a heartfelt place. That’s how you actually get someone’s attention, whether they deserve it or not. Send an email. Stop in to the brewery and ask to speak to someone. It's so easy to dismiss people on the other side of a Twitter handle, or a BeerAdvocate forum, or an attention-grabbing headline. Rage and incite if you must, but follow up with something thoughtful to seal the deal. You’d be surprised how easy it is to ignore the raging masses and the 140-character snowballs they constantly hurl. And also how completely impossible it is to look your customer in the eye and act like you don’t care.

After all, that’s how we raise our children. It’s how we can help our craft breweries grow up, too.