Stockholm is an amazing city. But no trip to Sweden is complete without an adventurous trek into the wilderness that occupies the vast majority of the geography there. So part way through our stay, we struck out for the Kolarbyn forests where for hundreds of years the locals slept away from town and lived in forest huts, built enormous charcoal pyres and spent their days chopping wood, canoeing and sitting by remote campfires.

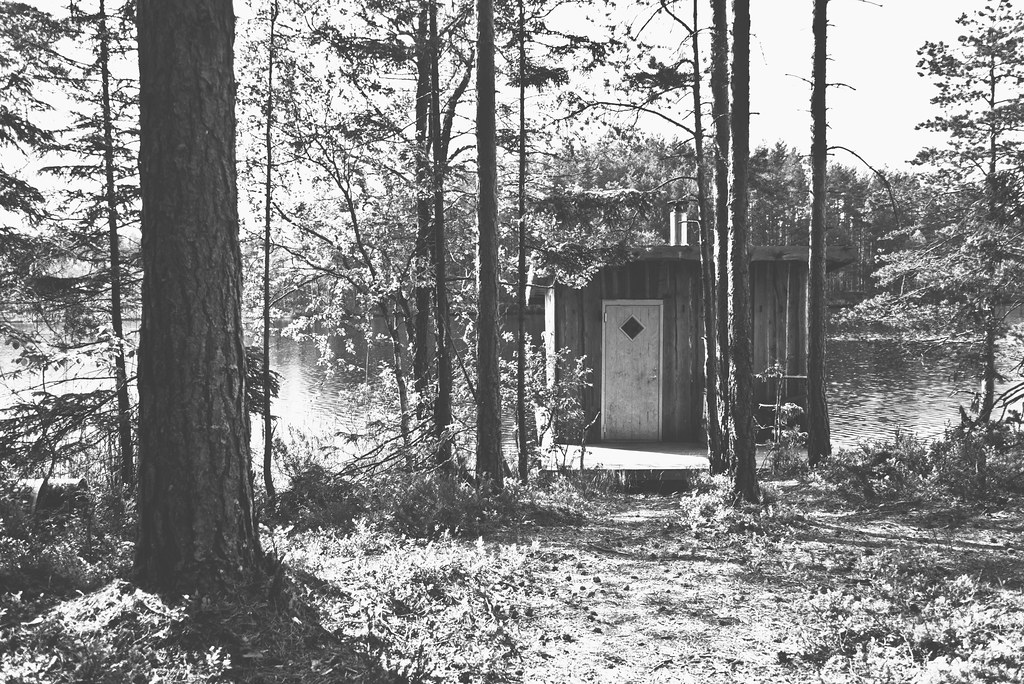

Our lodge, known as the Kolarbyn (translates to “charcoal”) Eco-Lodge was comprised of a dozen or so earthen huts, about 6 feet tall at their peak, and outfitted with two narrow wooden slat beds covered in sheepskins and a small stone fireplace. Situated on a lake, Skärsjön, the site is surrounded by seemingly never-ending forest, ferns and various bodies of water. Moose, wild boar and wolves populate the area far more than people. There is no electricity or running water, save for a nearby creek.

We arrived slightly pre-season, so we were the only guests, making for an incredibly quiet and slow three day stay. The isolation was invigorating.

In the morning, we split our own wood, started a fire and brewed coffee in a tin kettle. We made eggs and ate cheese and slowly let the aches in our legs and backs dissipate. By late morning, it was time for a hike.

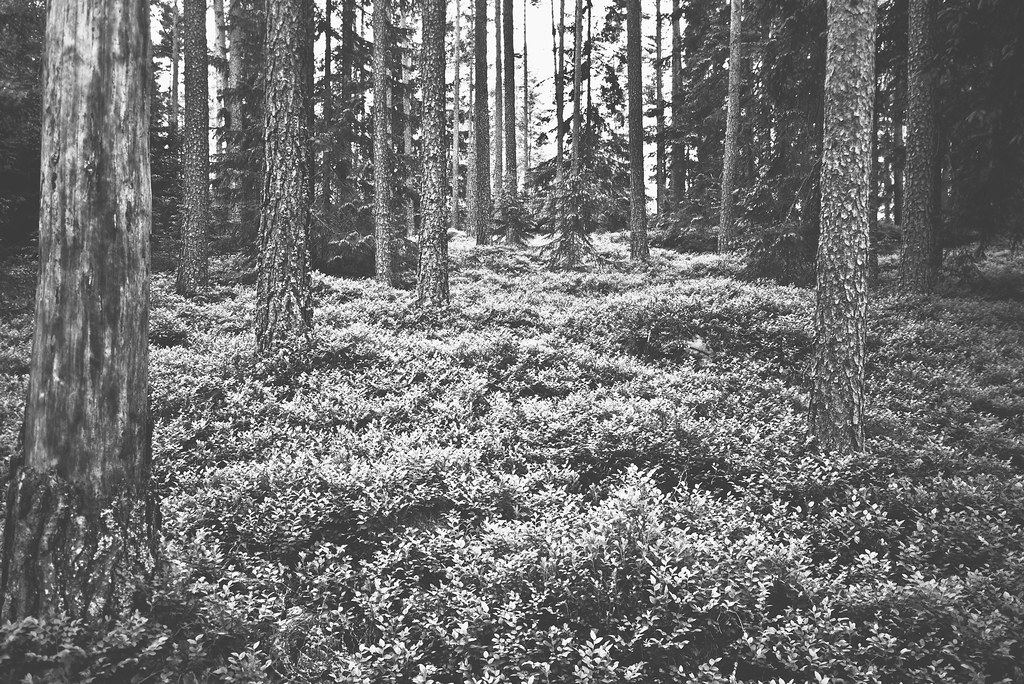

These are ancient forests, largely untouched. Fern fields hover three feet off the ground like the surface of Endor. And from time to time, we’d happen upon a miniature outpost of a forest gnome that someone had carefully pieced together to look both lived in, and recently vacated. Most of them, combined with the surreal quality of the forests, were entirely convincing. Also scattered along the way were remote outposts of some industrial sort or another reminiscent of abandoned Eastern Block military structures.

It was three hours to the nearest town of Skinnskatteberg, which made for an epic walk/beer run. There is apparently no town in Sweden without a System Bologet, the government-owned liquor store system. And even this far out, they carry a decent selection of beer. We picked up some pseudo-craft labels from Brutal Brewing, a newer Swedish label under the macrobrewer and beverage conglomerate, Spendrups. Mostly variations on pale lagers and ales, these made for perfectly adequate fireside brews.

Beer in Sweden is bought warm off the shelf. So for a camping contingent, we needed ice. But everywhere we went, we were looked at like crazy people. Grocery stores, pharmacies, even the gas stations had no idea why we would want ice in a bag. Back at camp, we settled for submerging our stock in the creek, which was still relatively cold in late spring. It did the job well.

Both of these pale lagers were perfectly adequate camping beers. They come in cans, get you buzzed and provide enough of a hop kick that your palate gets tickled. Pistonhead Kustom Lager is an organic lager dryhopped with a blend of cascade and amarillo hops to get the kick. Beervana has stronger citrus and grapefuit hop aroma, and finishes a bit more astringent. Both went pretty well with the moose meat sandwiches made from a local hunter’s recent kill. Bellies full, we retired to our hut, started a fire to fight the chill and fell asleep to the howling of a nearby wolf pack.

The next day, we set out onto the lake on an old rowboat. The glassiness of the water reflecting against the open sky was astounding. It felt like the water was somehow deeper than the sky’s infiniteness, as we were floating through it with barely a ripple, and only the creaks and moans of our wooden paddles against the fiberglass and metal joints to break the silence. Against such grand isolation, every noise seemed potentially disastrous, as though the boat could snap in two at any moment. Even the reeds hiding just below the surface tapped menacingly against the ridged bottom of the vessel as we floated further away from shore.

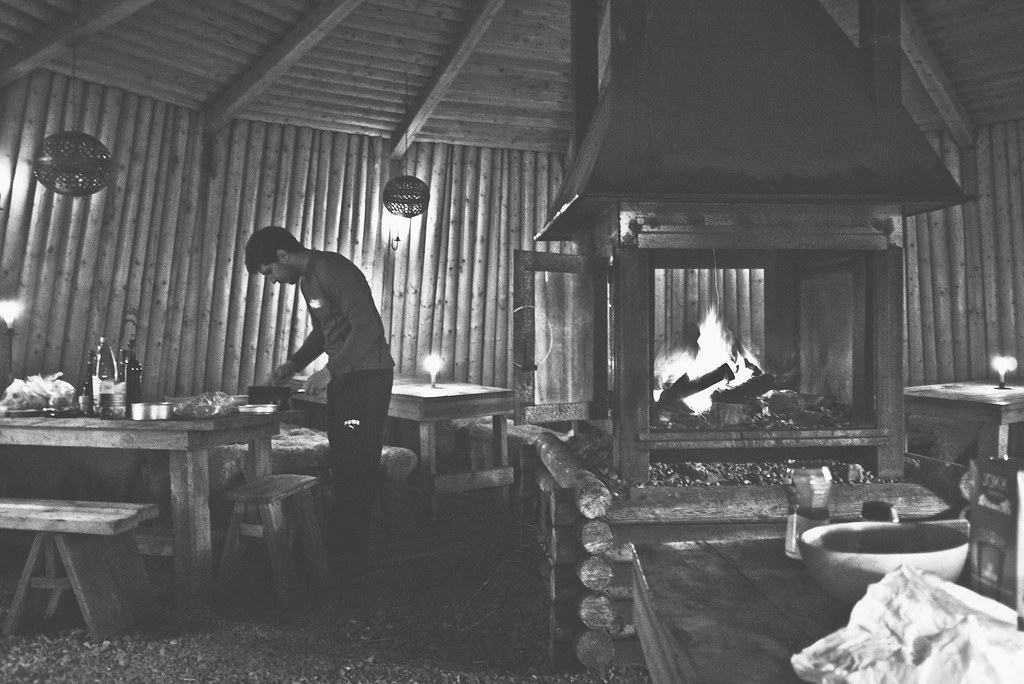

That night were were joined around the campfire by two French guys, both sports and recreation students at university, spending a three week stretch at Kolarbyn to help prepare them for the main camping season. They spent their days fixing roofs, chopping wood and building new seating and fire pits for the compound. Tired and hungry, they joined us for grilled wild boar and shared our wine (more convenient than beer without needing to be chilled).

Taking shelter from the rain, we congregated in a large yurt-like structure with a central fireplace and surrounding tables covered in sheepskins. Rémi made a batch of mulled wine from a recipe he knew, complete with citrus fruits and spices that came together in a beautiful, heady brew that warmed us all against the chilly storm.

Around eleven o’clock, with a small amount of light still filtering through the trees this far north, Hillary and I collected as many sheepskins as we could carry and made our way back to our hut for one last night’s sleep. Then we piled back into our Volvo S60 diesel in the early morning and turned towards Stockholm again for another four days of Swedish urban loft living.

Michael Kiser

Michael Kiser