“It’s not a job, it’s a way of life,” says Hukins Hops’ garden manager, Nathan Newick, as he steps away from the whir of the hop-picking machine.

Today is a busy harvest day at one of the area’s oldest family-run hop farms, a 120-year-old business that has been passed down through five generations. In that time, the Kentish hop industry has changed dramatically, but Hukins has remained committed to forging strong, two-way relationships with local brewers that help shine a light on the beauty of English hops.

Born near Maidstone, the largest town in Kent, Newick has been farming this land for the best part of three decades. The eight years he’s spent growing hops have given him a real appreciation for this unique crop. “It’s full-on, non-stop. It’s probably more hands-on than any farming industry I know, and I’ve done them all: arable, fruit, vines,” he continues, wiping grubby sweat from his brow as he catches his breath.

Inside the hop-processing facility, it’s boiling hot. Though it’s early September, the country is gripped by a late-season heatwave. Temperatures hover in the high 80s, and while clouds cover the sky for much of the day, there’s a muggy, humid feeling in the air.

It’s cooler in certain pockets of the hop garden, where the muddy ground slopes down and the trees planted around the site, part of a carbon-offsetting measure, provide some shelter. But knowing that a patch of heavy rain or wind could impact the picking schedule at any time—increasingly, extreme weather in the region is a real concern for growers—workers at Hukins have no choice but to manage in the heat, toiling among the bines for long hours. I watch tractors zip noisily from field to field as the farm surges toward the apex of its busiest season.

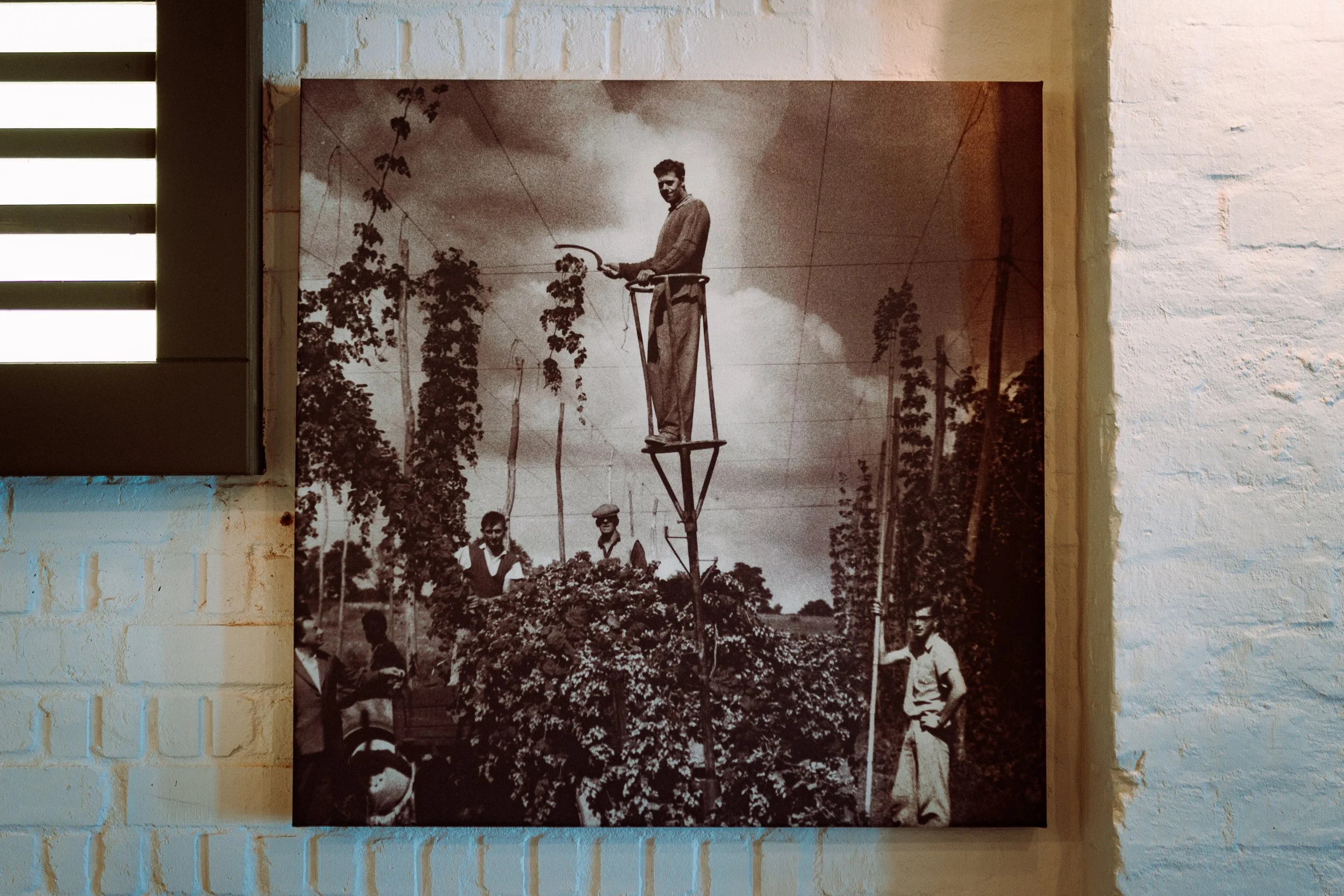

Every harvest season in England, workers like Newick enact an annual ritual that has been held in Kent for hundreds of years. England’s first hop garden was reputedly established near Canterbury in 1520; by the late Victorian age, the local industry had expanded so much that up to 200,000 workers from the East End of London would file into the county each September via dedicated trains from London Bridge, searching for hop-picking employment on a three-week “working holiday.” The pay wasn’t great, and conditions were often poor, but it was valuable time in the countryside, away from the oppressive smog of the capital.

During the second half of the 20th century, this tradition gradually died out. The development of new machinery such as Mr E H Burr’s mobile hop-picker, which was unveiled at The Royal Show in 1951 and could pick 1,000 bushels a day (equivalent to the work of 80 pickers), meant fewer workers were needed in the fields. And in the following decades, British brewers’ increased reliance on imported hops from continental Europe and farther afield meant Kent’s hop farmers faced shrinking demand. There are only around 50 hop farms left in England today, approximately half of which are in Kent. According to Ross Hukins—Hukins Hops’ managing director, and the fifth generation to oversee the business—those left are “diehard” growers who are “seriously passionate about hops.”

“It’s full-on, non-stop. It’s probably more hands-on than any farming industry I know, and I’ve done them all: arable, fruit, vines.”

The need for seasonal workers hasn’t completely disappeared, however. At Hukins, the farm’s core team is joined each harvest by eight workers from Romania, who stay at farm accommodation 20 minutes away and travel to the 50-acre Hukins site, in the village of St Michaels in the Weald of Kent, early each morning.

Throughout the day, trailers are loaded up and carted from the gardens to the hop-picking and -processing facility. Here, things are fast-paced, with 1,200 bines an hour hooked up and sent into the hop-picking machine, which claws off as many cones as possible. The process is steered by the seasonal workers, who are hired via a licensed agency and tend to “live in the U.K. for two or three years, earn some money and then go home,” according to Hukins. It’s common for seasonal workers to return to the farm year after year, basing themselves in rural Kent for a number of seasons before flying back to Romania after saving up a good chunk of cash. During this time, their experience and knowhow is invaluable.

One such worker is Aurica Haralambie, a compact, middle-aged man with tanned skin and a bushy black mustache. Leading the line of workers, he slashes the bines a couple of feet above the ground (this prevents injury to the root system), making his way through a vibrant green garden of Fuggles hops, tailed by a tractor and cloaked in heat—“Better than rain, innit!” shouts John Smith, the driver behind him. After picking a batch of Challenger, the team turns to Fuggle, although they’re well aware the harvest plan could change at any moment. As they finish off a row of bines, I wander over for a chat.

Wearing faded jeans and a dark blue T-shirt as well as shades, a white bucket hat, and a compulsory high-vis vest, Haralambie takes a short break as the tractor prepares to enter a new row. We share some brief formalities, although his limited English (and that of the bearded, bandana-wearing colleague he shares a cigarette with) makes it difficult to get into the details.

Tractor driver Bill Smith helps flesh things out a little. “I work from Monday to Saturday, starting early, sometimes until about 3 or 4 [p.m.]. It’s alright—it’s work, isn’t it—and you’re outdoors. And the smell of the hops is lovely.”

That’s definitely a perk of the job. As I walk through the fields, waves of powerful, zesty, complex hop aromas sweep over me. While Newick assures me that, just like the smell of the apple orchard he used to work in, “you do get used to it” and start taking the rich scent for granted, for now it almost overwhelms my senses.

I walk through a deeply aromatic row of bines later in the afternoon, seeking relief from the muggy air in the shade of the garlands. Comparing classic English hop Golding on the left and the New World-esque Ernest variety (first used in brewing trials in 1959) on the right, the contrast is notable. Not only are the higher-yield Ernest cones longer and fuller than Golding, with wilder-looking bines strung up into the sky, but their aroma is staggeringly potent. Alongside punchy citrus notes, there’s a touch of stone fruit, and a whiff of spicy, herbal tea that invites a third, fourth, fifth sniff.

“Changing palates are the driver for planting Ernest and Cascade and Bullion,” says Hukins. “We’ve got heritage varieties: Fuggle, Challenger, Goldings, Pilgrim, which are really the base you need for traditional cask beer recipes. We planted those American-style varieties, fruit-forward hops, to have a range of flavors available.”

Soon after I leave Haralambie to get on with his work, his team is directed toward a new patch of land, and it’s not immediately clear why. Eventually, word filters through that Hukins was concerned there wasn’t enough ripe Fuggle to fill a drying kiln, and decided to shift focus to the Bullion crop instead. It’s a reflection of the fluid, ever-changing nature of harvest season, when daily assessments of each crop—as well as the broader knowledge that hardier crops like Cascade and Ernest will generally flower later than the likes of Challenger and Bullion—help determine when each variety is ready to be picked.

When the time comes, it’s extremely satisfying work to observe. After Haralambie has sliced the bine from below, a colleague behind cuts down each garland from above while perched on top of a cherry picker. They’re collected and piled up in a trailer behind Smith’s tractor, which he slowly trundles forward.

“Last year’s harvest was absolutely terrible; we got hardly any rain. Everything was so dry that it would only take around three hours for the hops to dry in the kilns, but it’s usually around eight-to-10 hours. If we’re planting new varieties, we’re thinking: What’s gonna grow for the next 30 years?”

While the hours are long, the work seems fairly enjoyable, particularly when the weather’s warm. The heat does have its problems, however. Kentish farmers can no longer rely on getting sufficient rainfall each year, the upshot being that Hukins has installed a sustainable irrigation system that trickle-feeds the crops during the summer, using ditch water from the local area. More broadly, climate change is having a major impact on European hop harvests, and more drought-resistant, higher-yield varieties are increasing in popularity as a result.

“Last year’s harvest was absolutely terrible; we got hardly any rain,” says Hukins’ chief tour guide Dom Bowcutt. “Everything was so dry that it would only take around three hours for the hops to dry in the kilns, but it’s usually around eight-to-10 hours. If we’re planting new varieties, we’re thinking: What’s gonna grow for the next 30 years? Probably more hardier hops, like Cascade and Ernest.”

“Kent is getting hotter and drier,” says Hukins. “If I was given the chance to start a hop farm again, I wouldn’t choose Kent now, I don’t think. You’d want somewhere wetter and slightly less hot. Some of these older varieties like Fuggles and Golding are Victorian, and the climate then was so different. Even in September these temperatures wouldn’t have happened, and the nights were freezing.”

The pace of this harvest day only seems to accelerate once the workers leave the garden. The hops “go up into the lateral picker, which strips all the lateral and leaves the remaining hops,” says Newick. “Those big fans you can see down the ramp, that sucks all the leaf off, petal, and any gone-off cones or whatever, they go out the window, and then they go up into the oast.”

“Changing palates are the driver for planting Ernest and Cascade and Bullion. We’ve got heritage varieties: Fuggle, Challenger, Goldings, Pilgrim, which are really the base you need for traditional cask beer recipes. We planted those American-style varieties, fruit-forward hops, to have a range of flavors available. ”

A high-tech, modern kiln system designed to carefully dry each batch of fresh hops, the oast is a far cry from the traditional conical oast house buildings that remain dotted around the Kent countryside. This area of the facility completes the machinated process that allows Hukins to produce 50 million pints’ worth of hops in a good year. Still, even with the machines, this time of year is a serious grind for everyone involved.

“I started at about half four in the morning, and I’ll finish at about 10 tonight,” says Newick. “It’s a long day, but it’s still shorter days than I’m used to. Now I’m in hops, I wouldn’t change it. I enjoy it.”

It’s an attitude that sums up the pride and provenance associated with the Kentish hop-growing tradition. In the days surrounding my visit to Hukins, brewers from across Kent and London travel down to the farm to collect fresh hops, harnessing this three-to-five-week period to create special beers. In the weeks that follow, events such as the Kent Green Hop Beer Festival and the Five Points Green Hop Beer Festival in East London will celebrate this autumnal race against time, shining a light on the seasonal transitions that underpin the English hop-growing tradition.

“It’s a good time of year for the focus to be on British hops,” says Hukins. “We need brewers to reimagine their potential, and making green beer is a really good way of promoting the strengths of British hops.” As the farm moves through this busy period in the calendar, it’s this respect for locally grown hops and what they represent—a respect felt across the workforce—that makes Hukins such an electric place to watch the harvest unfold.