It’s 1998 and Tremaine Atkinson has just moved to Chicago from San Francisco. He’s out drinking with a friend. He doesn’t remember the bar, but if you’ve been to Chicago at some point over the past 25 years, you probably know the type: a dimly lit and unassuming neighborhood dive, often adorned with a red-white-and-blue Old Style sign that’s been yellowed by age. The city has thousands of haunts like it: The kind of place with working- and middle–class locals, cheap drinks, and an unpretentious vibe.

Around midnight, Atkinson’s friend offers to buy him a shot. Atkinson asks what they’re shooting and his friend says, “Don’t worry about it.” Atkinson is not prepared for what’s coming. The shot has a rich, golden-hued color. It smells pungent, with a heaping dose of grapefruit. He shoots it and is instantly taken aback by its bracing, lingering bitterness. He thinks, “What was that?” He feels like he’s been pranked. The shot’s flavor is so overwhelmingly bitter, and it lingers for far too long.

He sits with the taste: It’s awful, but interesting.

He will not try it again for years.

He’s just had Jeppson's Malört, a Chicago-made take on Swedish "bäskbrännvin," or bitter distilled spirit. What Atkinson doesn’t know is that this beguiling experience with the wormwood-based beverage (malört is Swedish for wormwood) would, in 20 years, lead him to buy the company and become its head distiller.

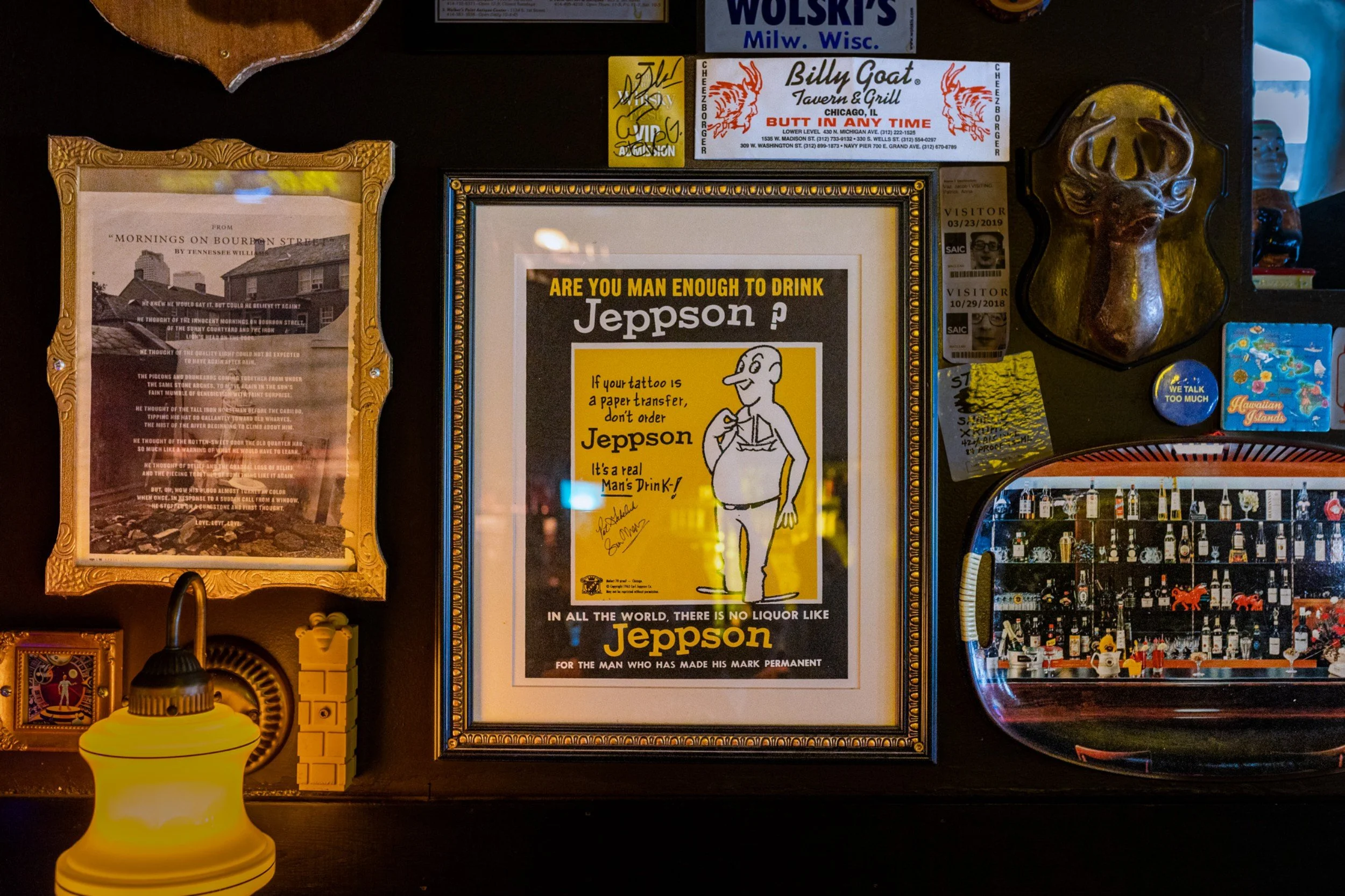

Jeppson's Malört is unique in how it’s simultaneously infamous, divisive, and fiercely beloved by Chicagoans and adventurous drinkers elsewhere. While you can sip it or put it in a cocktail, the primary mode of drinking it is by shooting it. It’s been called a “revenge shot” and “the worst booze ever.” The rapper Drake recently posted a photo of its bottle in his Instagram stories and mused, “There’s no way Chicago likes this.”

“The rapper Drake recently posted a photo of its bottle and mused, ‘There’s no way Chicago likes this.’”

But Chicagoans do love Malört and its palate-destroying experience: The fact that it’s so polarizing only adds to its mystique. Thanks to its in-your-face flavor of potent, bitter citrus, comedian John Hodgman has described it as “flavored with darkness and pain” and “it tastes like pencil shavings and heartbreak.” Still, he’s an avowed fan of Malört.

“...it tastes like pencil shavings and heartbreak.”

In fact, a lot of Chicagoans consider themselves diehard fans. In its near-100-year history, the bitter liquor has developed a serious cult following. Right now, Malört is the most popular it’s ever been. No longer the secret spirit found in Chicago dive bars, it is both reviled and relished in high-end restaurants like Split-Rail, and renowned cocktail bars like Scofflaw, in addition to most everyday neighborhood taverns like Rainbo Club and Cunneen’s. At any local bar, you can order a “Chicago Handshake,” which is an Old Style paired with a shot of Malört: the crisp, locally loved Lager washes down the bitter grapefruit rind of the shot. The name highlights how much Chicagoans love sharing this spirit.

Longtime Chicago bartender Val Capone (yes, she prefers to use her Roller Derby name) is one of Malört’s biggest defenders. She’s a fixture selling beer at Wrigley Field and tending bar at Wrigleyville dive Nisei Lounge, one of the most popular Malört bars in the world. Her first experience with the drink came over 20 years ago, when aggressively bitter flavors were not yet part of mainstream liquid diets in the United States. “It reminds me of how [my] grandmother would eat grapefruit for breakfast,” she says. “Eating it with a serrated spoon, sometimes you’d get a nip of the rind. It hits you in the back of your jaw, which is what Malört does.”

Compared to most spirits, which are typically bottled around 40% ABV, the digestif liqueur has a marginally lower 35% ABV, which could also account for some of its appeal. “I can slug Malörts all night and not get too drunk compared to Jameson,” says Capone. “I have Crohn's disease and some alcohols are gnarly on my insides, but I just noticed during shifts that Malört never had that effect on me.”

Capone isn’t alone in unironically loving Malört. When I had my first shot over 10 years ago, I became an instant fan. At the Gman Tavern, another Wrigleyville dive frequented by both punk musicians and Cubs fans, a regular there dared me to try it. He talked up its divisive and arguably disgusting tasting notes and said how much it's a staple in Chicago’s dive bar drinking culture. Worried I’d hate it—or worse, throw up—I still tried it. I instantly loved it. It settled my stomach, the taste lingered welcomely, and it went down much easier than tequila or vodka. In the decade since, whenever a friend visits town I give them the same spiel and buy them a shot. While Malört’s bottle once boasted, “During almost 60 years of American distribution, we found only 1 out of 49 men will drink Jeppson Malört,” my friends mostly love it. (However, one hated it so much he tried to fight me).

This combination of genuine admiration and loathing for the liqueur is what journalist and writer Josh Noel calls “The Malört Paradox.” In short, its shocking taste is part of its charm. “People ostensibly dislike Malört, but in that dislike comes a deep desire to want to share it with others, so that others can also experience it and dislike it,” says Noel, who is the author of “Barrel-Aged Stout and Selling Out: Goose Island, Anheuser-Busch, and How Craft Beer Became Big Business,” and is currently working on a book about the history of Jeppson’s Malört that will be out in late 2024. Fittingly, one of the many fake product taglines of internet lore humorously pokes at this exact conundrum: “Malört, when you need to unfriend someone in person.”

“Malört, when you need to unfriend someone in person.”

“I wrote about beer, spirits, and Chicago drinking for about 12 years at the Tribune,” Noel says. “Readers engaged with Malört like few other subjects. We all know there's a passion for the brand, but I also had very clear firsthand experience of that—you could see it in the readership numbers.”

This reader interest shows Malört’s rise from a dive bar shot to an unlikely source of civic pride—on its website, Malört uses the tagline, “A Chicago Icon.”

“To me, Malört is like the Chicago flag tattoo,” says Capone. “We like to embrace the city of Chicago here and the Malört bottle has the Chicago flag on it.”

Chicagoans often project an inherent toughness and hardworking sensibility: Winters are brutal, and as a mark of pride, the people who live here choose to stay in the midwest rather than move to the coasts. As Carl Sandburg’s famous Chicago poem goes, it’s the City of Big Shoulders. A place that is notoriously stormy, husky, and brawling. “Come and show me another city with lifted head singing so proud to be alive and coarse and strong and cunning," he wrote.

Malört’s bitter taste both reflects and hardens this ethos.

Much of Malört’s intrigue is its somewhat medicinal quality, which is also an essential part of its unlikely and winding history. Where a typical Nordic brännvin is made from potatoes, grain, herbs, or wood cellulose, Malört’s sole flavoring ingredient is wormwood, which is also used in absinthe. Dating back to the 1400s, Swedes infused wormwood into brännvin to treat stomach parasites.

What makes Malört such a divisive drink today also helped it skirt Prohibition-era restrictions on the sale of alcohol. When Swedish immigrant and local cigar shop owner Carl Jeppson started selling his wormwood-based concoction around Chicago out of a suitcase, the feds would taste it and conclude that no one would want to drink this stuff recreationally. They allowed Jeppson to peddle it as medicinal instead, per a loophole in the Volstead Act of 1919 that allowed sales of alcohol with a physician’s note (many of which were, unsurprisingly, often forged), until repeal was enacted in 1933.

Around this time, local lawyer George Brode began purchasing liquor recipes from local immigrants as part of his side gig with Chicago distillery D.J. Bielzoff Products Co., including Jeppson’s formula for Malört. The original bottle included a stem of actual wormwood and boasted the Chicago flag with three stars before the city added a fourth star in 1939. The tri-starred flag remains on the bottle to this date.

Eventually, Brode bought Bielzoff and sold off all of its brands but Malört. He renamed the company Carl Jeppson Co. after Jeppson died in 1949, moved production to Mar-Salle Distillery in 1953, and began marketing the spirit more broadly throughout Chicago.

While Malört didn’t burst in popularity in the 20th century, it did survive, mostly in working-class neighborhood bars, according to Noel. As the demographics of these places changed over time, the spirit likewise found new fans; for example, it’s not a stretch to think that Swedish expats loved Malört because it reminded them of the traditional Bäsk they drank back home. And as Swedish families on Chicago’s north side began moving to the suburbs in the 1950s, Malört gained a small foothold with other communities including Spanish-speaking and Polish-speaking immigrants. You can still find bottles in VFW halls and historic bars like the Green Mill and Simon’s Tavern, a Swedish watering hole in Andersonville that used to be a Prohibition-era speakeasy.

In 1966, Brode hired a 22-year-old legal secretary named Pat Gabelick. When she took the gig, she didn’t know he ran a liquor company, and when she tried Malört, she didn’t like it. In a 2009 Chicago Reader interview, Gabelick claimed that Malört’s early fans believed in its value as a digestif. One drinker brought Brode a bottle of his own kidney stones, thanking the spirit for helping him pass them. Also, the women who worked at the distillery would even take shots of the spirit whenever they experienced cramps.

When the last remaining Chicago distillery that produced Malört closed in 1986, Brode went elsewhere. After a brief stint making the product in Kentucky, Malört distillation ended up in Auburndale, Florida, near Tampa, where it stayed for over 30 years. When Brode died in 1999 and left the Carl Jeppson Co. to Gabelick, the company had sold 1600 cases that year.

Gabelick ran Malört out of her Lakeshore Drive condo for years following Brode’s death. She didn’t have a staff or a computer and continued to contract its distillation through Florida. As she continued her tenure heading the company, Malört began to grow faster than she could’ve ever imagined, thanks to what she calls, in a 2019 interview with The Ringer, “the hipsters.”

With the advent of social media in the late 2000s, word-of-mouth buzz about Malört spread from neighborhood dive bars to the internet. A popular page on Flickr called “Malört Face” began sharing photos of people’s faces immediately after they tried the spirit.

Many of these viral-ready memes and social media campaigns came from Sam Mechling, a local comedian and bartender at north side dive Paddy Long’s (now defunct), who also started a successful Twitter and Facebook page lampooning Malört. At his bar, he’d host an event called “The Malört Challenge,” where patrons would try the spirit, describe it, and the entries would end up on Mechling’s unofficial @JeppsonsMalort handle. A sample post: “I taste like a pigeon's nest in a grapefruit tree.”

By 2011, even though Gabelick had not spent a cent on marketing since Brode left the company to her, sales had climbed over 80% in just a few years, resulting in an annual revenue of over $170,000. In 2012, the company sold 3,200 cases, almost doubling the previous year’s total.

When Gabelick found out about Mechling impersonating the brand on social media and selling unofficial T-shirts at his bar, she—along with an attorney—visited him, intending to sue. But when she met Mechling, she was charmed by his genuine appreciation and love for Malört.

“When you look at a brand page [on social media]...you [can] realize it’s a parody account because it’s only got 150 followers,” says Mechling on a 2016 Good Beer Hunting podcast. “But our [parody account] was in the five and six-digit realm, so people just assumed [it was real]. And why should they think otherwise? What brand would allow this to happen? Well, one that was owned by a woman who didn’t own a computer.”

Instead of taking him to court, Gabelick ended up hiring Mechling to handle marketing for the small company. He was the only employee. What he lacked in company infrastructure, he made up for in savviness and self-awareness by making his Jeppson’s Malört social media pages the official accounts for the brand and starting a line of apparel and merchandise.

But the fact that Malört was distilled and bottled in Florida bugged him. It’s a product that’s originally from Chicago and still beloved in this city. Why shouldn’t it be made here too?

After a successful career in financial services, Tremaine Atkinson decided to pursue his real passion: making alcohol. He had previous, short-lived stints as an aspiring brewer but thought Chicago’s craft beer landscape was too crowded. So he decided to found CH Distillery in 2013, becoming Chicago's first distillery with a cocktail bar. As CH expanded its portfolio beyond vodka, Atkinson became fascinated with more obscure spirits like Fernet and Amargo de Chile.

“I picked up a bottle of Malört, saw that it was made in Florida, and thought, ‘That doesn’t seem right,’” says Atkinson. “So, a friend introduced me to Sam Mechling. We became friends, I’d visit him at Paddy Long’s, and we made a pact to try to get Pat Gabelick to allow us to bring it back to Chicago.”

Gabelick wasn’t initially interested. She had a good thing going: sales were increasing, she had one part-time employee in Mechling, and she could rest easy running the company from her condo.

“After five years of stops and starts, Sam calls me and tells me that Pat wants to retire and she thinks I should buy the company from her,” says Atkinson. “She wanted to travel and knew it was the right time.”

In October 2018, CH purchased the Carl Jeppson Co.—including the formula, the trademark, and the existing inventory of the finished product—and brought production back to Chicago to its headquarters in the southside neighborhood of Pilsen. They also kept Mechling in the fold.

“We did some math and figured that inventory will last five months,” says Atkinson. “Then news broke that Malört was coming back to Chicago, and the excitement around it meant that five months turned into three months.”

To make matters more tense, CH’s first test batch using the original recipe for Malört did not taste right. “We basically reverse-engineered the recipe,” says Atkinson. “We would make test batch after test batch.” While the flavor is important, Atkinson and his team were also tasting for the experience. Malört is all about the bitterness that overwhelms the palate, so when a batch goes down too smoothly, something is wrong.

“Malört is all about the bitterness that overwhelms the palate, so when a batch goes down too smoothly, something is wrong.”

Compared to CH’s Amargo De Chile, a take on Italian amaro that boasts around 19 different ingredients, Malört is a surprisingly simple beverage: there’s wormwood, alcohol, and a little bit of sugar. “When you start just changing one of those things a little bit, it radically changes the whole thing,” says Atkinson.

“The biggest challenge is to find a consistent source for wormwood, because there's a lot of variability,” he adds. Most wormwood is not used for food or beverage, but for supplements and medicinal products, so the taste is not even a consideration for most suppliers. “We have about five different suppliers now and our biggest job is to manage the variability of the wormwood itself. We've just learned different techniques and ways to try to balance things to try to keep it consistent.”

Under CH, Malört has remained remarkably consistent since the Chicago-made bottles debuted in 2019. “One of the things that I love about CH making it now is that the consistency of it is really nice: It's much, much smoother,” says Capone. “When you would get the Florida bottles, you'd sometimes have a bad bottle and sometimes you'd get a really good bottle.”

Since CH purchased the brand, sales have more than tripled according to IRI retail chain numbers. And they have also successfully introduced Malört to new markets. Where it once only had distribution in Illinois, Wisconsin, Indiana, and Louisiana, Malört is now in 30 states, including Washington, Colorado, and Minnesota.

Sales in Illinois still dominate. When CH took over, 90% of total sales were in Cook County, anchored by Chicago. Now, the statewide share is inching closer to 70%.

“Malört is really growing rapidly in other markets,” says Atkinson. “It's on the back of bar owners or bartenders who have lived or worked in Chicago and moved elsewhere. There's just this instant nostalgia that goes with it and you want to tell people about it. It's traveling well.”

The marked rise of Jeppson’s Malört is an astounding ascent. According to figures provided by Malort and reported by WBEZ, in 2008, when the spirit first gained social media notoriety, the company sold 300,000 shots in total. Fourteen years later, in 2022, that number skyrocketed to 7.9 million shots. To state the obvious: This is strange, but wonderfully on-brand. Companies universally track their sales in dollars and cases sold, not how many 1.5-ounce pours get thrown back at bars. That Jeppson’s Malört even charts the number of shots sold only solidifies its outsider charm.

As it increases in popularity around the country, it hasn’t lost relevance on its home turf. Chicagoans are still finding novel ways to enjoy the bitter liqueur. At Dark Matter Coffee, the roastery sells Malört-conditioned cold-brew coffee in cans, while Marz Brewing cans Malört Spritz. Elsewhere, you can attend Malört cocktail competitions, and see it featured with both earnest affection and tongue-in-cheek irreverence in cocktails at the best bars in town, like Mother’s Ruin, Osito’s Tap, and The Violet Hour.

On TikTok, @UnemployedWineGuy calls himself a Malört mixologist and tests out what happens when it is used as a base spirit in popular cocktails like Old Fashioneds and Ranch Waters. It rarely works. In his joke series “Malört Mixology,” he wonders if the spirit was “made with a dirty sock in a toilet,” grimaces dramatically whenever he tries his cocktails, and most recently hit (fake) “rock bottom” after a year of creating the Malört-centered concoctions.

But at Nisei Lounge, their Jeppson’s Malört infusions take the prize for the most novel way to enjoy the spirit. In fact, Capone’s official title at the dive bar is "Director of Malört Infusions for Nisei Labs at Nisei Lounge.” The first infusion started with the Christmas-themed Candy Cane Malört, where bartenders would just smash up candy canes and let them sit in Malört bottles. A fan favorite is the sport-pepper-infused Malört, which Capone calls “Sporty Malörty.” It’s a spicy, boozy spin on a Chicago hot dog ingredient. Other concoctions include unconventional and controversial infusions featuring pumpkin spice and Peeps. “I get really fun and really weird with it,” says Capone, who says the bar goes through multiple bottles of these creations a day. “It really just comes from whatever weird stuff our brains make up.”

From its Prohibition-era and Swedish roots to becoming a divisive dive bar shot that embodies the spirit of an entire city, the story of Malört is as beguiling and improbable as the spirit itself. “Chicago people love Chicago stuff, and Malört is uniquely Chicago—up there with the deep dish and Chicago-style hot dogs,” says Noel. “It resonated in that way, similar to Half Acre and Revolution. They're Chicago beer and this is a Chicago spirit.”

“Chicago people love Chicago stuff, and Malört is uniquely Chicago—up there with the deep dish and Chicago-style hot dogs.”

As Jeppson’s Malört transcends being a Chicago secret to a fast-growing spirit nationwide, the hardened and welcoming sensibility of the people who drink it spreads too.

“When you give someone a shot of Malört you're basically saying no matter what, you always have family in Chicago,” says Capone. “It represents Chicago so great because it is bitter but still beautiful.” It’s something to be shared, even if they hate it.