I get nervous as hell, and I don’t get nervous about anything.

By the time I step foot on that boat, I’ve thought about everything that could go wrong. We pull out of the no-wake zone and into open water, and I can feel the coat of anxiety wash over me. As the tannic, murky waters give way to turquoise, I’ve already what-ifed enough for a whole year. What if the motor goes out? What if heat lightning hits the boat? What if the GPS dies, and we all get severe sunburn?

A fishing trip like this requires coordination, and for everything—mechanical, climactic, and personal—to go right. Today there’s added pressure: My two best friends, who I’ve known for 25 years, are with me. We’re all carrying the wounds of pandemic-era stress and strain, of family members suffering from ill health. The world has felt grim and unrelenting, and I’ve coaxed them out onto the water with the promise that it will help us all catch our breath.

The farther out we go, the more I start to feel the worry melt into relief. As much as the logistics of a fishing trip cause me anxiety, the water—the rocking boat, the 100-foot depths, the sea breeze—has the ability to pacify, to provide a breather from life and all its woes. I can only hope that it will do the same for all of us, at this time of change and grief.

I grew up playing in the ditch as a youngin’, which was the precursor to fishing off the docks at Backman’s Seafood on James Island, South Carolina. My poor mother’s attempts to call me home were no match for the Lowcountry sun in the thick of summer—I would stand at that dock all damn day. Ask me what I caught, and I couldn’t tell you. I was having the most fun just being out there, taking in deep breaths of pluff mud, feeding my spirit in ways I couldn’t explain. Church was never really my thing—being near water always felt 20 times more divine than being asked by the pastor each Sunday to “look at your neighbor.”

My connection with water has always been there. I was a product of the beach, and as the years progressed, I learned how to fish, swim, crab, and surf. Each followed the other, marking a new phase of maturity: I’ve been swimming since a very early age, which granted me the opportunity to fish on the pier or dock by myself. Crabbing came next. I found surfing a couple years outside of being a teenager. That was until football took up all the real estate in my heart.

It was football that took me to Charleston Southern University—until I flunked off the team. After my parents’ storms of hurled cuss words, I transferred to Claflin University, the oldest and first HBCU in South Carolina, to redeem myself. It was my first time not playing sports, and my first time being more than a couple hours from any beach. Things had changed.

Even at Claflin, I couldn’t shake the habit of walking across campus wearing thong sandals, swim trunks, and a T-shirt; I was still a kid from Charleston. To my peers, I was the “beach homie,” dressed a little different but still playing Goodie Mob in the dorm room. That’s how I met two of my best friends: Dylan and “Chill” Will.

Dylan was the honors college homie, the one who did everything right. He drank a little bit, but not much. He had a steady girlfriend and lined up an internship every summer. “Chill” Will was the responsible homie: He worked at Foot Locker every weekend and had his own car throughout college. As we went through school, the bond among the three of us grew and solidified.

After graduating, we did a pretty good job of keeping in touch with each other, at least at first. I stayed in South Carolina to finish graduate school; Dylan moved to Atlanta to work as a civil engineer; “Chill” Will enlisted in the Air Force. We stopped talking as often—the jokes about Dylan being “country as hell” for drinking bottles of Pepsi filled with salted peanuts, or “Chill” Will washing his 1985 Chrysler LeBaron every Sunday, started to fade.

Years passed, and while the phone calls never really stopped, the in-person hangouts did. We’d always ask each other if we were planning to attend Claflin’s homecoming, but it never happened—children, marriage, and moving to different cities and states had a way of keeping us apart. We were all different people living full lives. By the time a global pandemic caught us off-guard, it had been years since we’d been together.

In February 2020, my mother suffered a stroke. Seven months prior, so had my father.

When my dad had his stroke in the summer of 2019, getting down to South Carolina to see him was easy. My parents divorced when I was two, and my dad remarried and had two more sons. Though the event was scary, the support was perpetual. Dad recovered pretty swiftly, minus the sporadic coughing due to his compromised swallowing. For my mom, on the other hand, recovery wasn’t so simple.

My mom suffered her stroke a few weeks before her 68th birthday, and a few weeks before COVID-19 brought about the closing of the world. Shortly after it happened, I drove down to Rock Hill, South Carolina to see her. She was in good spirits, as she typically is, and when it was time for me to head back to Baltimore, I’d told her and a couple of my aunts that I’d be back down soon. My aunt agreed that when my mom’s therapy and rehabilitation were complete, she would host her for a few months.

But the pandemic threw a wrench in our plans. My aunt became overwhelmed with the care my mom needed, and abruptly told her she had to leave, in the middle of quarantine. My mother, who is used to making things happen on her own, rode a short two-and-a-half hours down to Summerville to stay with my cousin, who had also been with her during the quarantine period.

After a few months, I still couldn’t drive down to see her for fear of spreading infection—even after my cousin left my mom to fend for herself without warning, once again. As my mother’s only child, I felt helpless, and the frustration, anxiety, and fear, combined with family tension, made those months even harder to bear. But despite what I thought then, I wasn’t alone in that pain.

On the tail end of my mom’s recovery, I gave Dylan a call. We didn’t miss a beat, just like the old times. We asked after each other’s wife and kids, laughed as we quoted “You So Crazy”—the usual banter. “Did y’all get it?” we asked each other about the virus that was upending our lives. Then I mentioned the situation with my mom. “Shit, my mom had a stroke too,” Dylan replied.

In a strange way, hearing that lifted the stress from my shoulders immediately. When the stroke happened, along with all the family disappointments, I never gave myself time to grieve. If anything, I fought it by going harder, and in return, I built up more tension. But hearing one of the homies say he was going through the same thing made it easier to cope with, knowing I wasn’t alone in how I felt. We spoke about our respective situations, our shared family woes and frustrations.

A few months later, Dylan and I spoke again. “How’s Mom?” we asked each other. And later, “Yo, what’s up with ‘Chill’ Will?” I asked him. “Man, he’s going through the same thing,” Dylan told me. His wife had also suffered a stroke. A quilt of gloom settled over the conversation.

When “Chill” Will and I spoke a few weeks later, I could hear the stress in his voice. I wanted to check his mind, and let him know that shit gets better. But while Dylan and I had had a few months to get through it, everything was still fresh for him.

At that point, I’d been thinking a lot about a book I’d recently read, “The Comfort Crisis,” which encourages embracing the hard things. “Humans have essentially evolved to believe that they can do a lot less,” says author Michael Easter. In our day-do-day lives—so much of which are spent cloistered at home with all our technology—we don’t do enough “hard shit,” even though that ability is innate within us.

One way to get better at that skill is to practice doing hard things, Easter says—away from screens; out in the world; real, physical experience. I decided to pull my boys into this belief, 30 miles offshore from Charleston. I set up a date for us to meet, to spend a day on the water fishing, and did my usual research to find a trustworthy, reliable charter. Their only job was to drive down—Dylan from Atlanta, and “Chill” Will from Philadelphia.

The night before an offshore trip is similar to the night before a big game. There’s anxiety, excitement, and a little fear that anything can happen. The peaks and troughs of emotion mimic life’s discomforts—the ones we’re unable to run from. Yes, it’s fun, and hopefully you’ll catch a cooler full of vermillion snapper. But it’s also hard-times practice.

Though our trip had been planned for a 7 a.m. departure, Lowcountry summer storms keep us waiting until 1 p.m. I have plenty of time to pick up Dylan from his hotel. We meet with daps, hugs, and smiles before collecting “Chill” Will at his parents’ house and driving to Shem Creek. There, we link up with Captain Darius, a retired Marine who now takes out charters. The Captain introduces himself and welcomes us aboard his 24-foot center console. Prior to the trip, I’d stocked my Ice Mule with strawberries, ginger ale, RX Bars and a six-pack of Hefeweizen from a local brewery to keep us going.

On the way out, we can see Sullivan’s Island. A $1 million boat zooms past us, and we pass by looming cargo ships in turn. After an hour-long ride, we reach our destination. The captain throttles down, and the silence of the idled engine immediately sets in. It feels like a different kind of presence. We all adjust to the new vulnerability of being in the middle of the open ocean, nothing between us and endless water except the hull.

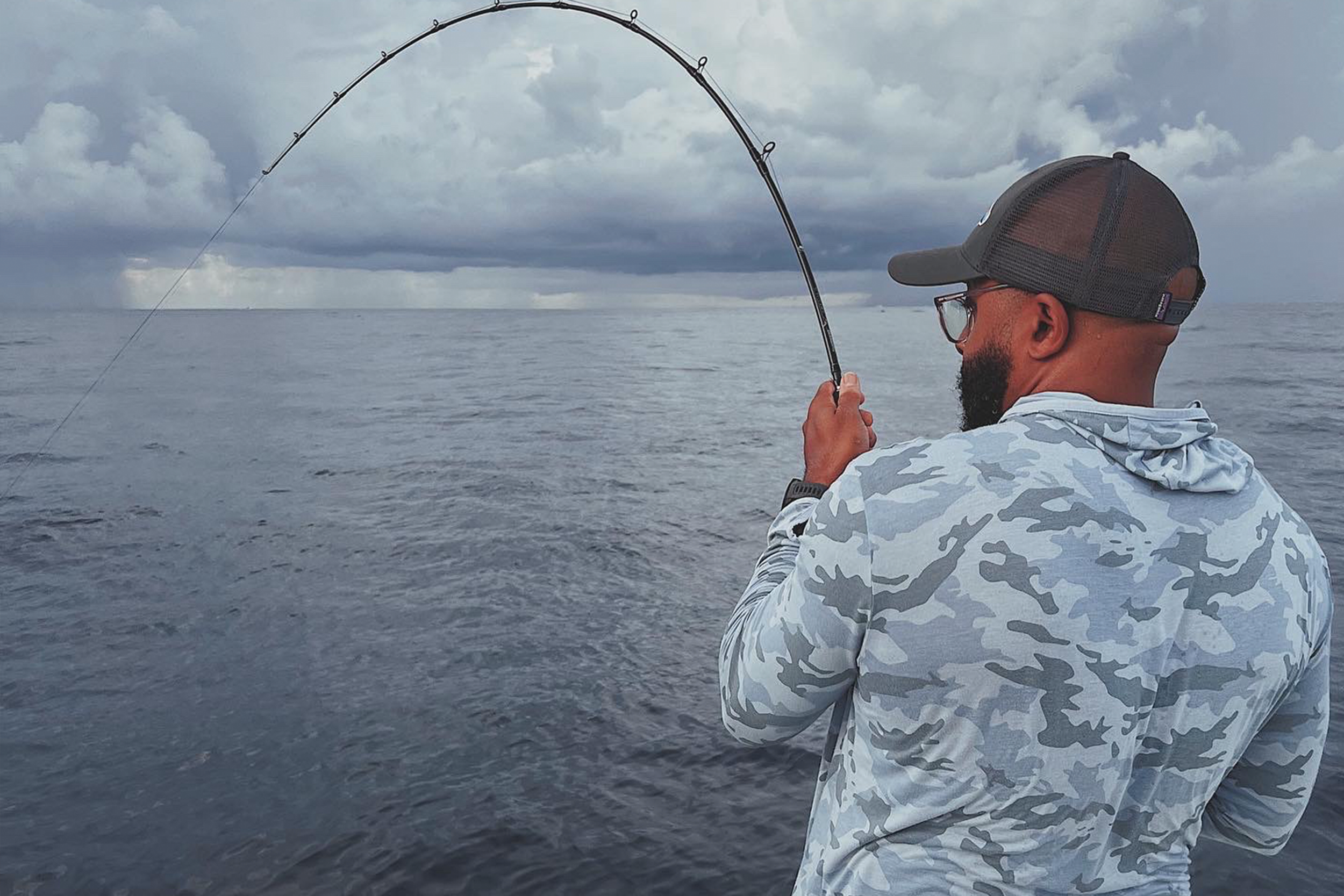

We’re bottom fishing in 100 feet of water, hoping for all the snapper and black sea bass we can catch. We crank the music up. Chill Will handles the Bluetooth as Captain Darius reels in the first vermilion of the day to the sounds of Project Pat.

A couple hours into the trip, “Chill” Will gets seasick. We don’t laugh, or panic; instead, we keep a close eye on him as we continue to fish. Later, the seas are choppy and he’s sick again, and so am I. It feels incidental at first, but then it occurs to me that this is our first time being vulnerable together outside of college.

Here’s the hard-shit practice, I think, the moving through discomfort and worries about what might happen together. It feels like something unlocks in us, like we’re experiencing and channeling the same complex emotions at once. Something about being miles offshore with no cell phone service, and thunderstorms in the distance, allows us to let down our guard—to lean on each other, to confront our fears about losing our loved ones. We allow ourselves to grieve, to show emotion and to admit it to each other.

By the end of our six-hour trip, it feels like our friendship has moved to a new phase, that we’re joined by a newly tight, silk bond. That we’ve worked out together how to be better men, better husbands, better fathers and better caretakers. And we manage to haul in a decent catch of vermilion snapper and black sea bass, too, even if the cobia aren’t biting.

Heading back in, Captain Darius navigates us around the storm clouds. After returning to dry land, Dylan and I walk back to my truck to grab the cooler. Fifteen fish later, we head 20 minutes down the road to a local seafood spot on James Island.

The Yelp reviews don’t do the restaurant justice. Reality is, locals love this place, and if you’re fortunate enough to bring your fresh catch in, the restaurant will cook it for you. After making our reservation, we grab two sea bass and two snappers, along with my filet knives, and head through the back patio and down to the dock.

A few patrons—a couple must be tourists—who are waiting to be seated inquire about our catch. “How much did y’all get?” “How was it out there?” “They’re gonna cook that for y’all?” The three of us, still on a high from the day, gamely respond to their questions and begin our duties. I filet the snapper, “Chill” Will guts the sea bass, and Dylan scales them with fresh water from the hosepipe.

As we wait to be seated, we talk about damn near everything under the sun, flowing between humor and commiseration. We talk about the fact that both “Chill” Will and I had to put our dogs down, that Dylan is teaching his daughter how to be comfortable with firearms. We’re only interrupted by a text message from the restaurant that lets us know our table is ready.

We sit, order some beers, let the waitress know we’ve got a fresh catch and how we’d like it prepared, and we keep talking. Again, that feeling from off-shore returns, and bonds us for the second time. We reflect on moving beyond our comfort zones, deliberately putting ourselves in a compromising situation, and finding the strength of vulnerability in that shared experience.

To celebrate, we tell stories, drink beer, release stress, and enjoy some damn good fried fish two hours removed from the ocean. We dissociate from past pains, and move beyond our past shyness when sharing vulnerabilities. And we reflect on the fact that togetherness is what shapes and improves us. Sometimes you need to head 30 miles offshore, in 100-foot depths, to really speak—to express the vulnerabilities that are harder to share on land.