There are scores of strange and beautiful places in Central Europe. And then there is Mikulov, in the Czech Republic’s eastern region of South Moravia.

The ancestral home of a branch of Austria-Hungary’s noble Dietrichstein family, Mikulov rises high above a surrounding plane, with the Dietrichsteins’ 300-year-old castle still holding court at the hilltop town’s peak today. Once the source of much of the wine consumed in imperial Vienna, just 50 miles (80 kilometers) to the south, the steep slopes of Mikulov are covered with winding grapevines, while terraced cobblestone lanes wind up, over and around the hill in a way that seems designed to protect those who live here.

That sense of refuge feels both innate and ancient. The thousands of Hebrew-inscribed tombstones falling over themselves under the shade of century-old fruit trees on the north side of town offer the last evidence of the vibrant community that settled in Mikulov, then known as Nikolsburg, after Vienna and the entire province of Lower Austria expelled their Jews in 1421. Just a few miles away is the spot where archaeologists discovered the Venus of Dolní Věstonice, a carved female figurine dating from around 29,000 B.C., making it one of the oldest pieces of human-form sculpture in existence. The area has also yielded stacks of mammoth bones, believed to have been slaughtered by the same Stone Age tribes who carved the Venus.

For many outsiders, the feeling here is somewhat disorienting—and not just because of the town’s maze-like streets and off-kilter stone staircases. Mikulov is in Moravia, and thus technically part of the Czech Republic, but the particular combination of light and stone here often feels like someplace else. The boulders that form the hill are masses of granite and limestone. The houses are painted with traditional folk-art flowers. The roofs are tiled in ochre. As the Czech poet Jan Skácel once wrote, “Mikulov is a piece of Italy moved to Moravia by the will of God.”

With such a setting, it makes sense that Mikulov might be much better-known for wine than for beer. But thanks to the brewery Wild Creatures, that might be about to change.

Over the past few years, bottles from Wild Creatures have been turning heads at leading festivals in places like Italy and Amsterdam, with imports coming to the U.S. through B. United since 2017.

This is where Mikulov’s unique location factors in. Despite residing in the Lager-focused Czech Republic, Mikulov’s most famous brewery doesn’t make anything like a traditional Pale or Dark Bohemian Lager. Instead, Wild Creatures exclusively produces spontaneously fermented beers flavored with local fruit, a style that brewery owner Jitka Ilčíková fell in love with while working in Belgium.

“My grandfather started the wine cellar, so I lived with wine and wine grapes all around,” Ilčíková says, pouring samples in her family’s vinný sklep (wine cellar). “And my husband worked for a winery, so I knew the world of wine from the point of view of a small producer.”

Jitka Ilčíková—her first name is pronounced like it starts with a Y, followed by a last name that sounds like someone has an ill cheek—remains a small producer herself. Wild Creatures only turns out about 67 U.S. barrels (80 hectoliters) per year. That’s still a big step up from her first homebrew experiments with spontaneous fermentation, which started back in 2011, while she was on maternity leave.

“My husband is a biochemist, and he is used to dealing with my crazy ideas,” she says. “He told me for over a year that it is not possible to brew spontaneously fermented beer here.”

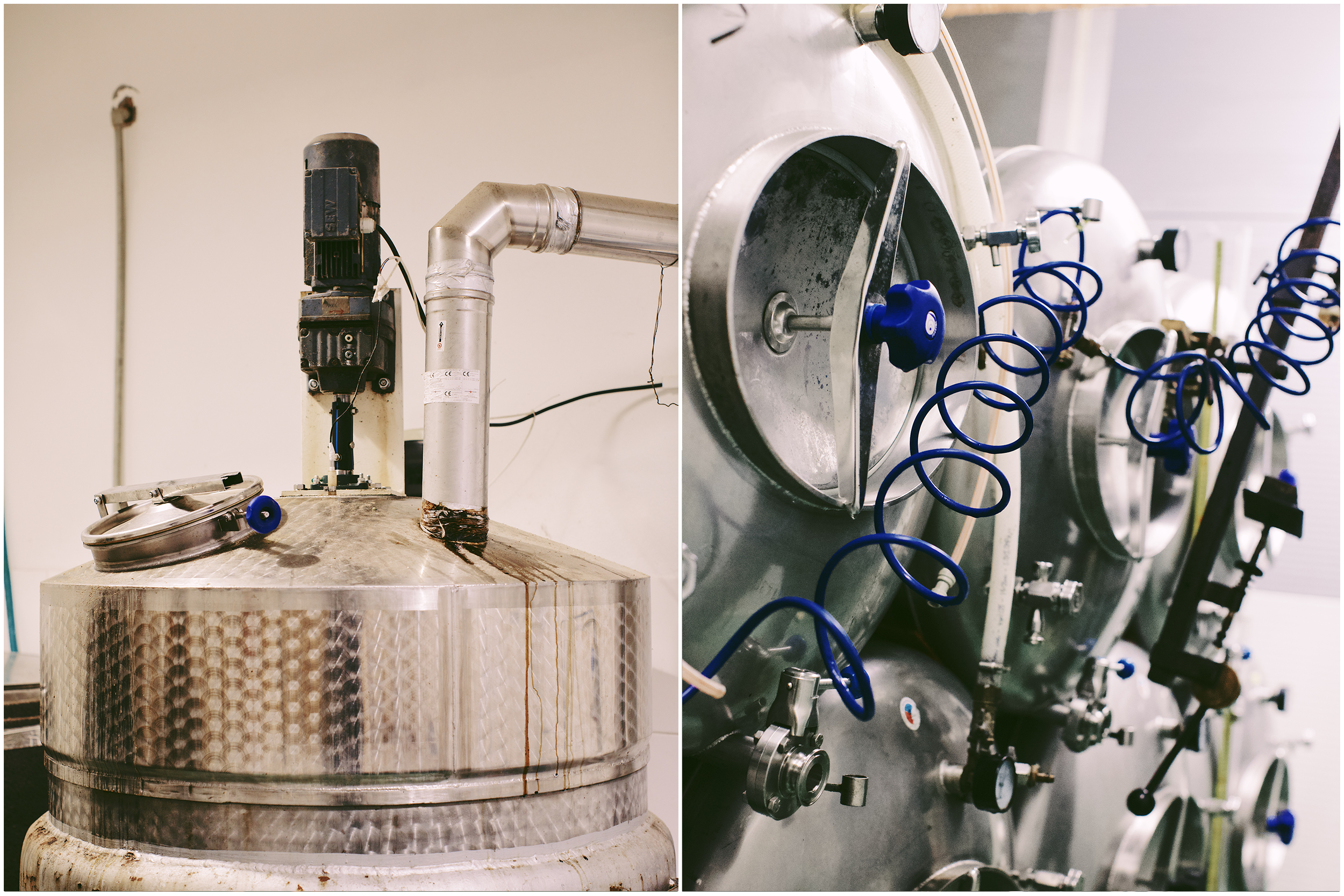

As it turns out, Ilčíková and her husband Libor are now almost competitors: in addition to his day job at a local winery, Libor runs the town’s only Lager brewery, Pivovar Mamut, named after the area’s favorite Stone Age quarry. The two share a two-year-old, purpose-built building on Mikulov’s Venušina, or Venus Street. Inside there’s a beat-up old brew kettle named Sputnik, which certainly resembles a vintage piece of Eastern Bloc space junk, though it was actually recycled from an old Moravian dairy. With a laugh, Ilčíková will tell you that Sputnik is indestructible.

In addition to the brewhouse, there’s a small barrel room for Wild Creatures’ beers. When you stop by, that barrel room might also hold several boxes of extremely smoky, almost buttery homemade bacon, left over from the family’s recent zabijačka, or pig slaughter. There’s no taproom, tasting room or visitors’ center, and you’d be forgiven for wondering if they’re planning to do more work on the place. But the main construction is all completed, at least enough for Ilčíková to brew, blend, and age beers to her taste.

For Wild Creatures, the process starts out with a mash that Ilčíková describes as “inspired” by a traditional Lambic turbid mash, generally made with mostly Pilsner malt, about 30% raw wheat, and a portion of Vienna malt.

There’s an inoculation vessel—Ilčíková doesn’t like to call it a coolship or koelschip, though she acknowledges that that’s basically what it is—where the wort gets exposed to Mikulov’s real “wild creatures” for about a day. After that it goes into oak.

“All the beers are individually fermented and aged in the barrel,” Ilčíková says. “After one year, we decide if we will blend it to harmonize the taste, or if we will use it as it is, or if we will let it keep.”

“People ask me why I am brewing an apricot beer. I wanted a beer that makes sense. That’s why we are not brewing a beer with kiwi. Because apricot is home.”

With one year in the barrel, plus time for aging, the minimum production time at Wild Creatures is about 48 months, Ilčíková says.

“I think we are not able to go under two years—none of our beers. It’s like wine. You need time to balance it.”

The first Mikulov beer to turn drinkers’ heads was Tears of Saint Laurent, named after the de-stemmed Saint Laurent grapes that were added to the beer after an initial year in oak. Although it is relatively obscure internationally, Saint Laurent has a long tradition in Central Europe, especially in the Czech Republic and Austria, where it ranks first and third in acreage, respectively, among grapes used for red wines. The resulting Wild Creatures brew has the plummy fruit aroma of a typical Czech Svatovavřinecké vino, but with much more structure and an elegant, dry finish.

In addition to Mikulov’s regional microbes, local fruit exerts a strong sense of place. In the Czech Republic’s western region of Bohemia, roadside stands selling apricots or plums might note that their offerings come from South Moravia in big letters, as a selling point. All of the grapes Ilčíková uses are from her family’s own vines. The apricots she adds to the beer Fly With Me are homegrown.

“I was born here, and I went away to Belgium and then I moved back here,” she says. “People ask me why I am brewing an apricot beer. I wanted a beer that makes sense. That’s why we are not brewing a beer with kiwi. Because apricot is home. We grow it everywhere here.”

The only fruits used by Wild Creatures that don’t come from Ilčíková’s own land are sour cherries. The greater Mikulov area is home to more than 10 types of sour cherries, she says, all of which are different in a clear way: one variety was developed to be juicy, while other varieties might be more aromatic, or sweeter. Eventually, she found the exact type she wanted in the orchard of a friend, who then allowed Ilčíková to take over the production of those trees for her sour-cherry version of Fly With Me.

Despite Ilčíková’s time in Belgium, Wild Creatures’ beers are definitely not straight-up Lambic imitations. The sour-cherry version of Fly With Me tastes distinct from the average Kriekenlambic in a number of ways, and for any number of reasons, from the local microflora that produce the base beer to the Mikulov-specific fruit that is added. And naturally, Ilčíková’s personal tastes play a role in the final product.

“You will not recognize a lot of Brett in our beers,” she says. “It is there, but it is not something that I want to emphasize. When we are blending the beer, we hardly discuss it at home, because Brett is not wanted in wine and we lived with wine production before we started with beer.”

That winemaking influence shows up often. Perhaps the most interesting beer in the brewery’s portfolio is Resurrection, which takes inspiration from Central Europe’s greatest dessert wine: Hungary’s Tokaji Aszú.

“I find her project very interesting—so brave and full of passion. Her family roots, linked to wine made with local grapes, is a great weapon in her hands.”

The traditional “puttonyos” sweetness levels of Tokaji Aszú—which start at 60 grams per liter and rise all the way up to 150, not counting the syrup-like Aszú Eszencia—make for quite a challenge. Lambic-type microorganisms have a remarkable ability to keep consuming sugars, leaving most unpasteurized, spontaneously fermented beers dry and not sweet.

“It was not easy how to find the solution. It is not easy to make a spontaneously fermented beer that is sweet,” Ilčíková says. “The target was to meet the flavors of Tokaji Aszú, and to have a higher amount of residual sugar with the help of osmotic pressure.”

Effectively, the beer’s sheer density solved the problem. According to lab analysis, Resurrection has 60 grams of residual sugar per liter, she says, putting it at the same level as a 3 Puttonyos Tokaji Aszú. It was made with an addition of Ilčíková’s own Moravian Muscat and Pinot Blanc grapes. Before adding the grapes, she first hung the bunches in the attic to concentrate the must, a traditional method for making dessert wines in the region, on the small wire hooks people normally use to decorate Christmas trees.

“I ordered 10,000 Christmas hooks in September, and the company called and asked, ‘Are you sure?’” Ilčíková recalls. “And I think after four months, 40% of the liquid was gone.”

The result is sweet, slightly oxidized, fragrant and full. On Untappd, one rater of Resurrection wrote that he didn’t know if he was drinking beer, mead or port. He gave it 4.5 stars.

With its tiny production and obscure location, most drinkers won’t ever have a chance to rate a Wild Creatures beer. And the praise from the specialists who know Ilčíková’s work is only likely to make those bottles more desirable.

Jan Lemmens organizes the Carnivale Brettanomyces festival in Amsterdam, where Ilčíková presented four of her beers last year. She’s scheduled to offer another tasting at the event in 2019.

“It was extremely well-received,” Lemmens says. In particular, he noted the audience’s reception of Resurrection: “That clearly blew people’s minds. It was amazing.”

The Italian beer writer Lorenzo “Kuaska” Dabove first sampled beers from Wild Creatures at the 2016 Salone del Gusto, an international specialty food show in Turin. Afterwards, he brought Ilčíková on stage alongside Cantillon’s Jean Van Roy, presenting Wild Creatures next to one of the best-loved Lambic breweries in Belgium.

“I think we are not able to go under two years—none of our beers. It’s like wine. You need time to balance it.”

“I [then] invited her to Arrogant Sour Festival 2017, where her beers were strongly appreciated by the visitors,” Dabove says. “I really love her brewery and her beers. I find her project very interesting—so brave and full of passion. Her family roots, linked to wine made with local grapes, is a great weapon in her hands.”

When you talk to Ilčíková, you get the impression that Wild Creatures might have gotten slightly out of hand, since it was only meant to be a project she could work on while staying home with her young children. Nowadays, Wild Creatures takes up most of her time. And parenting takes back from Wild Creatures.

The brewery isn’t quite finished, Ilčíková says, because she and her husband needed to buy their musically inclined daughter a new cimbál, or cimbalom, a piano-like relative of the hammered dulcimer that remains a popular instrument in Central and Eastern Europe.

In addition, some of Ilčíková’s time goes to Mikulov’s volunteer fire brigade. “I joined because of my son. He loves the fire department,” she says, laughing. “And now I can hook up the hoses as fast as anyone.”

She sometimes has trouble getting outsiders to understand exactly where she’s coming from, especially foreign fans who want to visit the brewery while they’re touring the Czech capital, about 155 miles (250 kilometers) away. “People know the beers from home, and they land in Prague and get in touch. And I have to explain that I am not in Prague,” she says.

If she holds a tasting in a pub, it probably won’t be in a traditional Prague-style hospoda, but rather in a cool and damp Moravian wine cellar, formed out of a natural cave in the middle of town. Look up and you’ll see that the walls are the same granite and limestone boulders that make up Mikulov’s Kozí Hrádek, a jutting, craggy peak, known locally as the “Goat Castle,” which overlooks the South Moravian plane. There’s an accordionist playing polkas and the other guests are dancing and drinking too much wine, as they have here for centuries, even millennia.

When she hosts a tasting of her wine-influenced beers, she usually tells people to expect something other than wine or beer. We’re still in the Czech Republic, even at this weird little southeastern end of it, and if she says “beer” most tasters will think of a classic Czech Lager.

Instead she tells them to think of a cider—both fruity and acidic—which she finds a good way to prepare the uninitiated for her spontaneously fermented brews. Despite the grapes she grows and uses, despite the clear winemaking influence in all Wild Creatures’ beers, the last way Ilčíková wants to describe a glass to tasters here in Mikulov is that it is anything like vino.

“If I say ‘wine,’ they expect wine,” she says. “We are in South Moravia.”