In 1988, an aspiring American homebrewer named Jeff Lebesch traveled to Belgium in search of inspiration. He spent his days cycling through towns and idyllic Belgian countrysides, stopping along the way to taste beers that spurred on his own brewing ambition. Three years after returning home, Lebesch established New Belgium Brewing Co. with his then-wife, Kim Jordan, in their hometown of Fort Collins, Colorado.

The Belgian influence that made the company’s heartbeat tick wouldn’t end there. In 1996, a young, Belgian brewer named Peter Bouckaert—who until then had worked at the Rodenbach Brewery in Roselare, West Flanders—joined them. Bouckaert helped establish what would become the largest sour brewing program in the United States, as well as taking over from Lebesch as brewmaster when he left the business in 2009.

Along with a handful of American breweries established over the past three decades—including the likes of Allagash in Portland, Maine and The Lost Abbey in San Marcos, California—New Belgium would go on to define what it meant to be a Belgian-inspired brewery in a modernizing American industry. Even its flagship Fat Tire—a beer that is distributed throughout the United States—takes its cue from so called “Speciale” Amber Ales from Belgian producers such as Palm and De Koninck.

[Disclosure: New Belgium is an underwriter for Good Beer Hunting.]

“‘Belgian,’ when I moved to the U.S. in 1996, meant sour, high in alcohol, or funky,” Bouckaert says. “I think this is still true, although we’ve maybe discovered a bit more differentiation in sours. It’s funny that Belgian ambers such as Fat Tire—a quintessential Belgian-style beer—does not get viewed as such in the U.S.”

In January 2018, after more than 20 years with the company, Bouckaert left New Belgium to follow a new path. Alongside his wife, Frezi, and business partners Zach and Laura Wilson, he founded Purpose Brewing in Fort Collins in May 2017. Unsurprisingly, Purpose is heavily influenced by Belgian brewing tradition, from its soft and complex barrel-aged sours to quirky glassware (in that they reflect more traditional Belgian as opposed to modern American vessels), it uses to serve them. Their longterm plan is to take their influence one step further and acquire a farm outside of the city from which to run their business—perhaps an attempt at discovering the true ethos of Belgian farmhouse breweries.

When he first arrived in the U.S., Bouckaert’s initial perception was that few American brewers drew influence from his home country. Perhaps a reflection drawn from moving from one very distinctive brewing culture to another. Instead, he saw several interpretations of German- and English-inspired styles, but didn’t consider much variation between them—at least compared to what was available in Belgium at the time. As such, Bouckaert saw a brewing industry that was primed and ready for its own Belgian-shaped epiphany—one that, with his experience as a young and enthusiastic Belgian brewer, he could perhaps help to spark.

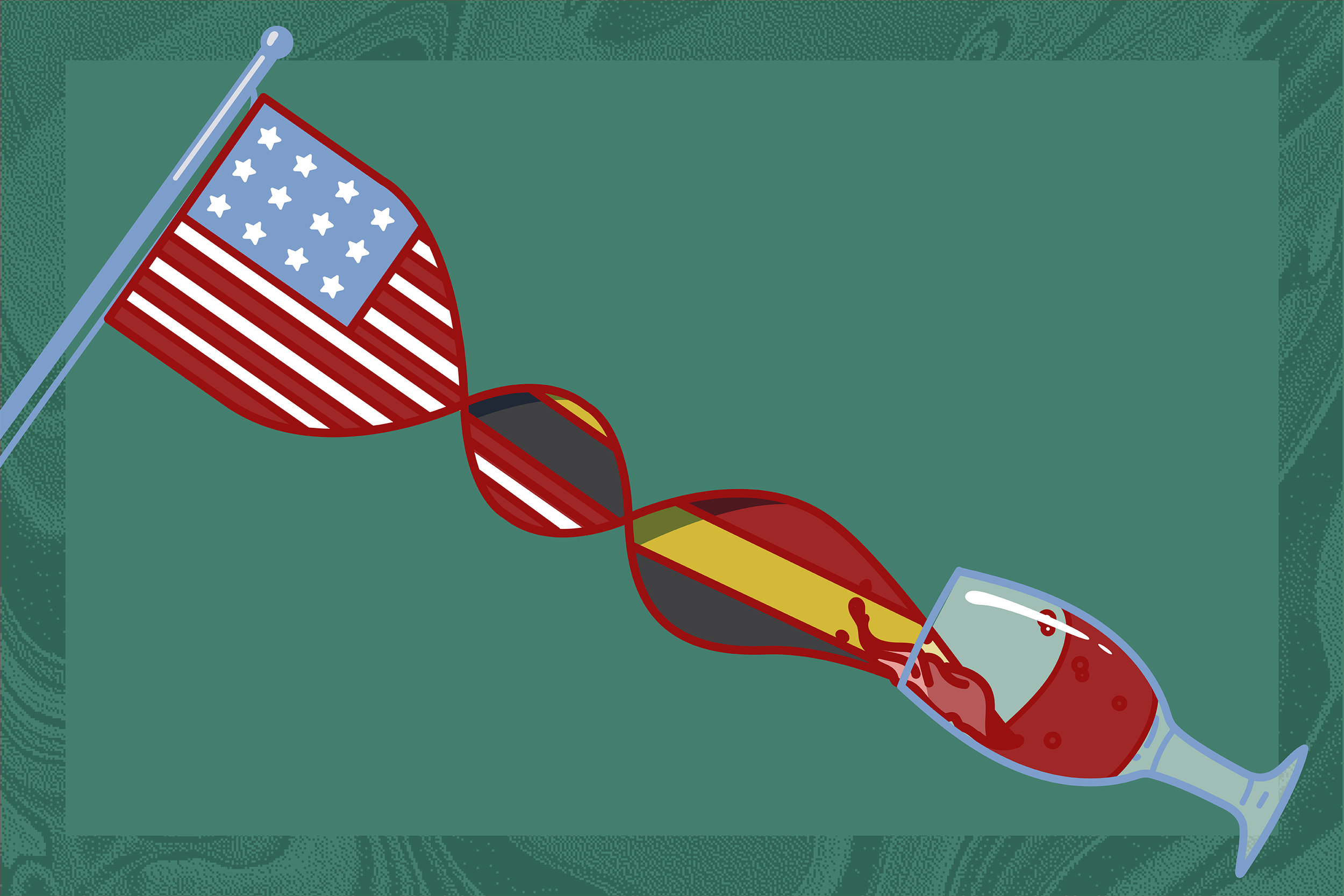

“Belgium’s influence came relatively late [to the U.S.], but was waiting to be discovered,” he says. “It has been very influential for a decade or so but I think there is more of a balance right now, where Belgium and the U.S. are mutually influencing each other. It’s been funny to see that coolships almost have become almost a fad now—it’s a fun rediscovery of an old method.”

It’s difficult to underestimate Bouckaert’s influence as a brewer in bringing Belgian styles to American palates. From sweetly satisfying Dubbels and dry, prickly Tripels, to intensely complex foeder-aged sours with layered waves of funk and acidity, you could rightly say he’s helped American drinkers understand what “Belgian” means in the modern era. Before this could happen though, brewers had to figure out how to take their Belgian influence from its zygotic phase to the core of their beer making.

The revival of the coolship (or koelschip in native Flemish) can be attributed to a number of factors on either side of the Atlantic. Alongside barrel aging, the large, flat, steel or copper trays used for cooling and inoculating wort with wild yeast have become a signifier of experimentation in modern brewing. In Belgium itself, organizations like HORAL were hugely influential in the revival of native styles like Lambic and Gueuze. In fact they’ve succeeded to the degree that it’s now inspiring a new wave of sour beer brewers all over Europe and the U.S.

In the U.S., an increasing amount of breweries look to Belgium for inspiration when it comes to sour beer brewing, embracing the challenge of expanding historic, European styles to new audiences. But in typical American fashion, they break this down to the most minute of details. That could involve isolating a particular strain of Lactobacillus or Brettanomyces for barrel inoculation, or operating a mobile coolship that can harvest yeast and bacteria from a specific location. America is a nation that takes inspiration to the outer limits—but how can that be “Belgian-inspired” when the root of that inspiration is set in a country that has spent generations working to maintain brewing traditions?

“Right now, we're lucky as brewers,” says Jason Perkins, brewmaster at Allagash Brewing Co. “U.S. beer drinkers, on average, are looking for new flavors and new flavor combinations. And that lets us be really creative with what we brew.”

Belgian beer is about the creation of something unique and almost undefinable, he adds. “American brewers—whether they know it or not—have picked up the torch of Belgian creativity and are running with it.”

This drive for variation and creativity in Belgian-inspired beer can often take attention from other styles that draw influence from the nation. More often than not, these are styles that sate thirst, not curiosity. Beers like the Witbier, which for a brewery like Allagash has been equally—if not more so important—to its development than any of its more extreme experimentations.

“The Belgian tradition has basically two parts. One part is these strict styles, like a Wit or Tripel. The other part allows pretty much any ingredient to be fair game,” Perkins says. “Many of Belgium's most well-known beers don't fit a style. Whether or not it's conscious, American craft beer is generally following this blueprint. You have some defined styles like Wits, IPAs, Lagers, and so on. But then you also have this wild creativity in what modern American craft brewers are putting into beer.”

Pioneered by the likes of Peter Bouckaert and breweries like Allagash over the past two decades Belgian influence on the U.S. has gradually spread throughout the nation, even to unlikely towns such as Decatur, Georgia. Like many brewery owners before him, Brian Purcell found inspiration on a road trip around Belgium—his back in 1994. Almost two decades later he’d open Three Taverns Brewery, serving its beer starting in July 2013.

“One of my earliest brewery slogans that still lives in the bones of Three Taverns is 'Belgian Inspiration, American Creativity,”” Purcell says. “I didn’t want to be confined to brewing beers made with Belgian yeast or traditional Belgian ingredients and brewing methods.”

For the former homebrewer-turned-brewery owner, “Belgian-inspired” is synonymous with “Belgian-style”—beers with the distinct estery funk produced in fermentation by Belgian yeast. Purcell points to traditional styles like Tripels or Saisons as examples of this. His vision for Three Taverns involved balancing this Belgian inspiration with what he sees as a more “open minded” American interpretation.

The brewery’s New Monastic series is the perfect example of this balancing act, showcasing beers that are Belgian at their core, but dressed in very American-looking clothes. Inceptus, a wild ale that uses its own wild Georgia yeast strain, is matured in wine barrels sourced from vineyards in the north of the state.

The best laid plans don’t always turn out how many a brewer hopes, however. For Purcell, that meant that American-style IPA would also become a driving point for this Belgian-inspired brewery, accounting for roughly half of its sales. Despite this, Three Taverns remains committed to producing Belgian-influenced beers, as its an essential part of the Georgia brewery’s ethos.

“It was vital that I defined Belgian-inspiration and how it would inform our brewing philosophy over the coming years as we ventured further and further outside the monastery walls, so to speak,” Purcell says. “That’s why my view of Belgian-inspiration is clearly defined on our website.”

According to Allagash's Perkins, being Belgian-inspired is “the throughline of basically every beer we've ever brewed,” He says being a Belgian-inspired brewer is about ensuring his brewery creates beers with some kind of tie to Belgian brewing tradition. This could be as simple as a Belgian yeast strain in a beer like Allagash White, or as complex as years of maturing spontaneously fermented beer in barrels, before blending their contents into a finished product, as with its Coolship series.

“The spirit of Belgian brewing is a guiding force in our innovation at the brewery,” Perkins says. “It's as relevant for us now as the day we started.”

While the U.S. has spent the last couple decades drawing inspiration from traditional Belgian brewing, several Belgian brewers have been observing this from across the Atlantic with interest. The use of deeply aromatic, fruit-driven American hops now has the same appeal with younger Belgian brewers as their own brewing tradition has had in the U.S. With the brewing world becoming ever more interconnected, through social media and the ease of international travel, the two brewing nations have never been closer.

“Belgian brewers now take their inspiration from U.S. brewers when they make a Saison, and it's the U.S. market that has pushed a lot of non-traditional Belgian Lambic brewers to make these in the traditional way again,” says Yvan de Baets of Brussels-based Brasserie de la Senne. “And these beers are often easier to find in the U.S. than in Belgium!”

De Baets maintains that the cyclical nature of influence has not seen his brewery take cues from American brewers. He does admit, however, that he draws a great amount of inspiration from the sessionable, balanced beers of Germany and the UK. And, despite not planning on brewing his take on a New England IPA anytime soon, this hasn’t stopped Brasserie de la Senne from collaborating with Belgian-inspired American brewers such as Jester King and Bagby Beer Co. He also doesn’t see Belgium as the inspiration to brewers that it once was.

“The U.S. brewing industry is now fully mature,” he says. “I think, though, that Belgian beers still have some influence when the key is balance, as this is something some of us are good at. And at some point, people always go back to balance.”

Despite de Baets seeing his country’s influence on the wane, many American brewers still view Belgium as a source for fueling creativity. Even brewers best known for slinging hazy, opaque-yellow juice by the four-pack maintain that being “Belgian-inspired” is at the center of their ethos. But in a market driven by a seemingly never-ending obsession with IPA, being Belgian-inspired no longer has to mean that a brewer’s output is rooted in that tradition.

“We started off our brewery with the singular focus of brewing Belgian-ish beers. We found Belgian beers to be intriguing in their diversity and malleability,” says Henry Nguyen, founder of California’s Monkish Brewing. “For us, we return to Belgian beers as a constant source of inspiration and purpose and nuance. It's obvious for Monkish that we found our sense in the Belgian monastic brewing tradition.”

Even when Nguyen turned a greater focus to his brewery’s production of IPAs, he says that Belgian influences were at the heart of it. For Monkish, this meant a primary focus on yeast and fermentation. Presenting and preserving a house character within its beers is vital to the California brewery, whether that character is found within a can of juicy IPA or under the cork and cage of a nuanced, fouder-aged Saison.

Perhaps this is what it means to be Belgian-inspired in the modern American beer era. As in other parts of its culture, be they culinary, literary or anything else, the U.S. has had the advantage and privilege of pooling its inspirational resources, putting its own wholly American spin on the product of that inspiration. Belgian beer is as much a catalyst now as it has always been to American brewers. From the foeders of California’s Monkish to the coolship of Maine’s Allagash, it demonstrates how wide that influence has been, from breweries old and new, coast-to-coast.

“The quirky system we've been running since we opened six years ago, the local water, the inefficient brewhouse layout, all have forced us to create beers using what we have on-hand. In doing so, the beers become ours and our beer embodies Monkish's identity,” Nguyen says. “Being Belgian-inspired is more of a posture and outlook on beer and brewing, rather than a style or subset of beer.”