So much of Anthony Bourdain’s work flies in the face of what conventional publishers and storytellers will tell you is acceptable for today’s audiences. What they won’t tell you is that such an opinion is based in a deeply rooted disdain for those audiences.

No one reads longform anymore. People want quick hits. They want the short video. They want the listicles and the how-tos. They want disposable content. Anyone who’s written for a magazine or produced episodic content for a TV show knows the pressure well. And it’s a lot different than the pressure we already put on ourselves to be succinct. Rather, this is the pressure to pre-grind the sausage so the grinder barely has to turn.

It’s an unfortunate cycle that leaves audiences—which should be edified, respected, and made prosperous—feeding off the content equivalent of processed gruel that will pass through our bodies quickly while still resulting in the cha-ching of the cash register all the same.

There aren’t a lot of examples that someone in my position can look to as proof that it is, in fact, a lie. Publishers, writers, designers, and photographers are overwhelmed by the power of “this is how it’s done.” But to me, and many of us here at GBH, Bourdain stood out like a North Star, reminding us that there’s a path, however invisible and seemingly remote, that cuts through all the noise on the ground. If followed long enough, that path will eventually reveal a destination that few others had the patience and perseverance to follow.

We all might spectacularly fail. But his encouragement has made all the difference.

—Michael Kiser, Creative Director

When I first encountered No Reservations in high school, I gravitated most toward Anthony Bourdain's gravel-voiced snark. He taught me to swear like an adult—that is, with insouciance, and frequently. Going to a new city? Fuck the tourist joints and head straight to the market, no matter how far-flung. He taught me not to fear offal: tripe, sweetbreads, kidneys. Ordering “difficult” dishes, eating heart, became a trick I liked to show off at dinners out. I wanted to be him, or some incarnation of him, always wearing leather and fearless by default.

Over time, my appreciation for what he did deepened. Watching him tromp around the world in his pointed-toed boots, I imagined bigger adventures for myself than anything I'd previously considered. When I was pure-green, when it counted, he showed me how writing and travel and a love of food and drink could cobble together into a career, a viable mode of life. (That I'm writing this from a hotel room in a country I've never visited before—here to see breweries and take photos and meet people—is not lost on me.)

Then, too, I learned about restaurants from him. Not just their unseemly underbellies, as revealed in Kitchen Confidential, but their magic as transitional hubs of hospitality—the luminous way a good restaurant, whether humble or high-end, can become a home anywhere. He believed that loving restaurants is inextricable from loving the people that make restaurants, and that getting to know those people was worth a traveler and an eater's while.

To remember him is to honor a polyphonic person. A cook of hedonistic appetites. A prolific writer of essays, fiction, and cookbooks. A vocal champion of the marginalized and discriminated-against, from women battling sexism to the Latin American chefs who keep American restaurants running. A peripatetic storyteller. A television host of unique charisma and vision. A profoundly kind and curious person.

Following Tony's example, I didn't just learn how to scoop out bone marrow and puddle it onto a piece of toast—I learned how to suck the marrow out of life generally. His loss is a terrible enormity for everyone lucky enough to have found in him, as I did, an open, more adventurous way to live.

I often get asked this question: “If you could have a beer with any celebrity, living or dead, who would that be?” My answer is usually something terribly contrived. I might pick my namesake, Ian Curtis of Joy Division, or perhaps his former bandmate Bernard Sumner. I’ve picked poets like Larkin, political figures like Marx, and most of the great philosophers. But in truth, I wouldn’t actually want to have a beer with any of them. It’d likely be awfully dull.

And then there’s Anthony Bourdain. In my arrogance, I thought that maybe, just maybe, one day that might actually happen. Surely the worlds of food and drink writing are small enough. Now that he’s gone, I want for that moment more than ever.

I got into beer before I got into food, so I came to Bourdain’s work pretty late. But when I discovered his writing (in all of its gorgeous, unbound, Gonzo form), I devoured it, much like he might devour one of his favorite In-N-Out Burgers. Animal style, naturally. Most recently, I’ve been poring over his latest cookbook, Appetites. I’ve cooked the lasagna so many times that the pages are now caked with Béchamel.

The next time I cook, it will be difficult. So will it be every time I replay an episode of No Reservations or Parts Unknown. But I will keep watching them, because his brilliance is timeless. His humanity was his greatest quality, and it transcended everything he ever did.

In case you’re wondering, I’d order us IPAs, probably, which we would wash down with a High Life or two, and maybe some bourbon. Then we’d get into the Negronis before heading into the night in search of the kind of comfort you can only find at the bottom of a bowl of noodles.

I can still see Anthony Bourdain skidding across the ice at the start of No Reservations, as if he would come ripping through the television. The show’s launch in 2005 coincided with two key shifts in my life—a peak in my restlessness to travel, and hitting a point where I finally had the funds to do so. At the time, most food shows were very predictably about how to make food and what you see when traveling. No one but Bourdain was exploring the value of food or places to an actual human being.

I didn’t think much about why I was drawn to the show back then. I knew that I loved how he threw out “fuck” any time he felt inspired. How he often wore jeans and a simple black t-shirt. How his guides were rarely chefs or anyone with a culinary background. He felt unapologetically real to me. I loved that he told stories of how food wasn’t just an end in and of itself, but a means to connect with family, friends, and strangers. Comfort and consistency in times of political and humanitarian crises. A compass to guide each generation in the traditions of their culture. Whether fine dining or street food, Bourdain captured the soul and meaning of a meal and tethered it to the people making and sharing it.

Like so many others, he had (and will always have) a profound effect on how I try to capture moments, either in writing or through photography—stripping them down to a facial expression, a gesture, any detail that relays the emotion. It’s really fucking hard, but Bourdain created an environment where people felt heard and trusted him with their story. It’s something I aspire to.

I was not an early Anthony Bourdain adopter. Watching those first years of No Reservations felt like a chore. While I would be enthralled with the depth of his knowledge, and amazed at all of the places he was visiting, he, as a host, was a bit much. Those early years of Bourdain’s east-coast cockiness just didn’t mesh with my Midwestern earnestness and insecurities. I was a broke 20-year-old starting to wrestle with the realities of adulthood. Watching someone live so freely, working the best job in the world? That was a hard pill to swallow.

I’m so happy I happened to return to No Reservations during season five, episode 15—Sardinia. Bourdain was visiting the home country of his second wife with their daughter. I noticed almost immediately that he was different. Maybe it was due to the partnership he shared with this woman, or the affect of becoming a father for first time, but he’d changed. The perspective and depth of nuance he now leant his destination was staggering. The trademark snarkiness would never go away, but now it took a back seat. He had become less of a visitor, and in his own way, a statesman.

As a privileged, white, small-town-Nebraska-raised man, Bourdain provided a model for me of how to be curious, respectful, and to celebrate cultures and their cuisine without portraying one’s self as an expert or legitimizer. He ran toward his ignorance looking for answers and shared his knowledge with confidence and compassion. Between No Reservations and Parts Unknown, he left us with a valuable lesson—how to be a guest.

A year ago, I was scrolling through the unceasing processional of 140-character shitposts that is Twitter when I caught a familiar headline: “Bob Dylan obliges annoying fan in Berkeley by actually playing 'Free Bird.'” This was a dumb, funny article I wrote two years ago, mainly because it amused me, but here it was now, organically appearing on my timeline like it was new. Why was I seeing this now? I looked at who retweeted it and couldn’t take a screenshot fast enough: It was Anthony Fucking Bourdain.

In the days since he died, it seems like everyone has some story like that about him. A fleeting interaction, an amiable conversation during a book signing, a remembrance of some sagacious aphorism culled from Parts Unknown. It’s hard to believe that any one person’s existence could be so ubiquitous, but that legacy befits him, a person who seemed to enjoy engaging and entertaining everyone equally, from presidents to busboys. He’d immerse himself, consume their stories and eat their food, language barriers be damned.

Bourdain made a career—or, rather, a life—of openly musing about the joys of sharing food, and the inherent humanity that is exposed when two strangers break bread (or tripe, or a fetal duck egg, or cobra heart, or whatever).

Maybe it was never really about Monday’s fish or some exotic entrée, but why someone made it, why someone ate it, and why we care about any of it. I try to remember that in my beer writing. It’s really not about the beer at all. It’s about the fact that it starts a conversation, and that it could be a vehicle for understanding each other. That is, if we decide we want to listen.

“Later, I would tell friends that if I found out that Bourdain had committed suicide, I wouldn’t be surprised.” I wrote that in 2014, describing what it had been like to meet the man and spend a long day filming with him in 2009. Today, I feel bad for having made such a coarse and uncaring comment, though it was sadly true. When I met him, he was obviously miserable. He had it all, and he hated it. And yet, most people only saw the bon vivant, the great traveler.

This is partly why it's been disappointing to read eulogies for Tony by people who didn't know him. Most of what I’ve read from people who had never met him seems inaccurate, incomplete, or just plain wrong. In my eyes, Tony was not a particularly “fearless traveler.” As far as I could tell, he did not “enjoy life to the fullest.” In real life, he was certainly not as tough or as snarky as his TV persona would have you believe.

Tony was a smart, sensitive, sad man who loved books—writing them and reading them. He showed obvious pride in his mystery novels, which relatively few read, rather than the nonfiction which made him famous. (I’ve heard a ton of people talk about how much they loved No Reservations and Parts Unknown. I haven’t heard anyone say anything about Bone in the Throat.)

I get that “Anthony Bourdain”—the public figure—meant a lot to people. He meant a lot to me, too, especially before I got to meet him. I understand that part of what it means for someone to matter is that the rest of us project our hopes and dreams onto them, to have them become the “blent air” in which “all our compulsions meet, are recognized, and robed as destinies.” But we’re not doing the real Tony any favors by believing that our projections about “Anthony Bourdain” were completely real.

From what I saw, blind adulation was not something he particularly enjoyed. To be honest, I didn’t witness him enjoying much at all during our time together. We had some real laughs and a couple of great conversations about our favorite books and writers. But the man himself was obviously unhappy.

I’m sorry I wrote what I wrote, even if it was true. And I’m truly sorry he’s gone.

I first saw Bourdain’s work in high school, long before I would find myself writing about, taking photos of, and traveling for, food and beer. I was impressionable, insecure, and utterly fascinated with this wild man traipsing around the globe. I would regularly watch hours of No Reservations and dream of a life like his.

What I’ve realized the past few days since he left us was the immeasurable impact he had on how I approach food and travel. Sure, his writing and gorgeous shows helped shape my voice, but really, it’s the way he lived that I see in myself most. Why waste time on a bullshit tourist attraction when there is so much living to be done, culture to experience, and food to eat in every damn town across this great earth of ours?

Tony emboldened generations to find, and experience, their boundaries. To flirt with them and push them just a little further. I will always carry that curious spirit with me. Thank you, Tony, for this wonderful gift.

When it comes to food and drink writing, context is everything. When the taste of that amazing hop bomb or aged Lambic is gone, it's the moment you'll remember most. That was what Bourdain did best. In his writing, he was visceral. His films transported you. Not everyone can portray that humanity and drag you in with them.

I learnt as much about myself as I did about others while watching Parts Unknown, and his infamous rant about beer geeks on their phones in pubs keeps me in check every day: "A bar is to go to get a little bit buzzed, and pleasantly derange the senses, and have a good time." That's exactly how I'll toast to him.

I don't know if you've figured this out about me yet, but I'm kind of an asshole. I'm sarcastic and confrontational and unforgiving. And it was seeing those same qualities in Anthony Bourdain that gave me some hope for myself. Because underneath his rough exterior and matter-of-fact nature was a genuinely curious and courteous and respectful human. And he got to do what many people would kill to do for a living. So there had to be some hope for me, right?

Even beyond what he meant to me on a personal level, he completely changed the way I travel. His approach to new places, his attitude toward locals, his appreciation of customs: all those things had a profound effect on me, and became the Travel 101 I needed in my younger days. Equally as important, in some cases even more so, was the breadth and wealth of his knowledge of locales. I can't even begin to count the number of times I've typed "anthony bourdain [city name]" into my phone, or the number of times it's resulted in exactly what I needed.

For those reasons, and so many more, I will miss him.

I've got a saying: I don't like you until I like you. With some people, the shift happens fairly quickly. With others, it never happens. With Tony, it was never like or not like, only love.

One day, food was functional, just calories for the day. The next? I watched an episode of No Reservations. Everything changed.

I started with certain preconceived notions: the food and the chef were everything, there were rules to follow, there were restaurants you were required to visit. But Bourdain shattered much of that. There on screen, I watched as he rubbed elbows with the culinary greats, but also readily offered a “fuck that” attitude, professing his desire to eat from a street vendor’s cart instead. His stance was jarring and refreshing. He eschewed the chef’s coat for a t-shirt and flip flops. And he didn’t give a shit if you, or anyone, took offense at him skirting “the rules.” In many respects, he welcomed people into the food world who perhaps felt they had no right to be there.

He blended travel discovery and food discovery so seamlessly, you didn’t notice. Is Parts Unknown a travel show with a food underpinning, or is it a food show that travels to lesser-known locales? In his world, which became ours, Paris and New York City were obvious, but Vietnam and West Virginia were where it’s at.

My wife and I enjoyed a meal at Noma recently. The plates and my memory are already starting to battle it out. But what remains crystal clear is my walk to the front of the restaurant with the perfectly still lake just off to my left, the greeting the staff gave us as the door flung open, and the conversations with friends. I suspect one day I’ll not remember a single plate served that evening, but I won’t forget my wife sitting to the right of me, the laughter and conversation we shared. I think that was Bourdain’s point all along.

Dealing with a celebrity’s death is often perplexing. You feel bereaved. You mourn their loss as though they were an old friend, though you never actually knew them. Somehow, they spoke to you on a level that seems impossible.

I never knew Anthony Bourdain. To be honest, the first time I became aware of him was when he ripped into the craft beer industry for “turning people into zombies.” In the past couple of days, I’ve read loads of his work, and I’m painfully aware of the talents we’ll miss. I can see why so many of my friends credit him as the reason they do what they do.

For a great many of those friends, Friday was a difficult day. I was reminded of when Chris Cornell died. A brilliant, prolific, and talented creator, his music was incredibly influential during my most formative years. As a pissed off teenager, Soundgarden resonated me. It wasn’t until he passed, however, that I realized how much he meant.

I’m listening to Soundgarden as I write this, drinking a delicious beer. As I look around me, a few people in this pub are inputting tasting notes on their phones. I chuckle and go back to my beer, though I try not to pay it too much mind. After all, it’s just a beer, right?

As the news hit the internet on Friday, and then seemingly became all of the internet, I kept wondering, “Why him?” I had no idea Anthony Bourdain was suffering. Why would he take his own life? I mentioned it in passing to a friend at lunch that day, and she quickly reminded me that there’s a lot we don’t know about people.

Revisiting his work over the past few days has been fun, but not without its cringeworthy moments. He had a bit of a persona for a reason, after all. But, as Spencer Hall wrote on Friday, “Along the way, he changed... He ended up somewhere else completely: As a truly conscientious traveler, as one of the only men to really publicly examine his role in encouraging terrible behavior in the restaurant industry.” He came such a long way, even in just the past few years. Imagine if he'd made it to his seventies! There’s a lot we don’t know about people—and that includes the way they’ll improve over time.

On Friday evening, waiting on to-go dinner and still processing it all, I scrolled through my Twitter feed, which was filled with extremely personal stories from people—some I follow from afar, others I see every day—laying bare their bouts with depression, suicidal thoughts, and more. There amongst them was my friend from lunch.

I ugly-cried to “Farewell Transmission” on the drive home thinking about the ones we’ve lost along the way—including the song's author—and about how so many of the ones still here who are suffering on the regular, oftentimes in secret. I don’t have the answers, but I have learned there’s a lot we don’t know about people. I’m trying to be more mindful of that every day.

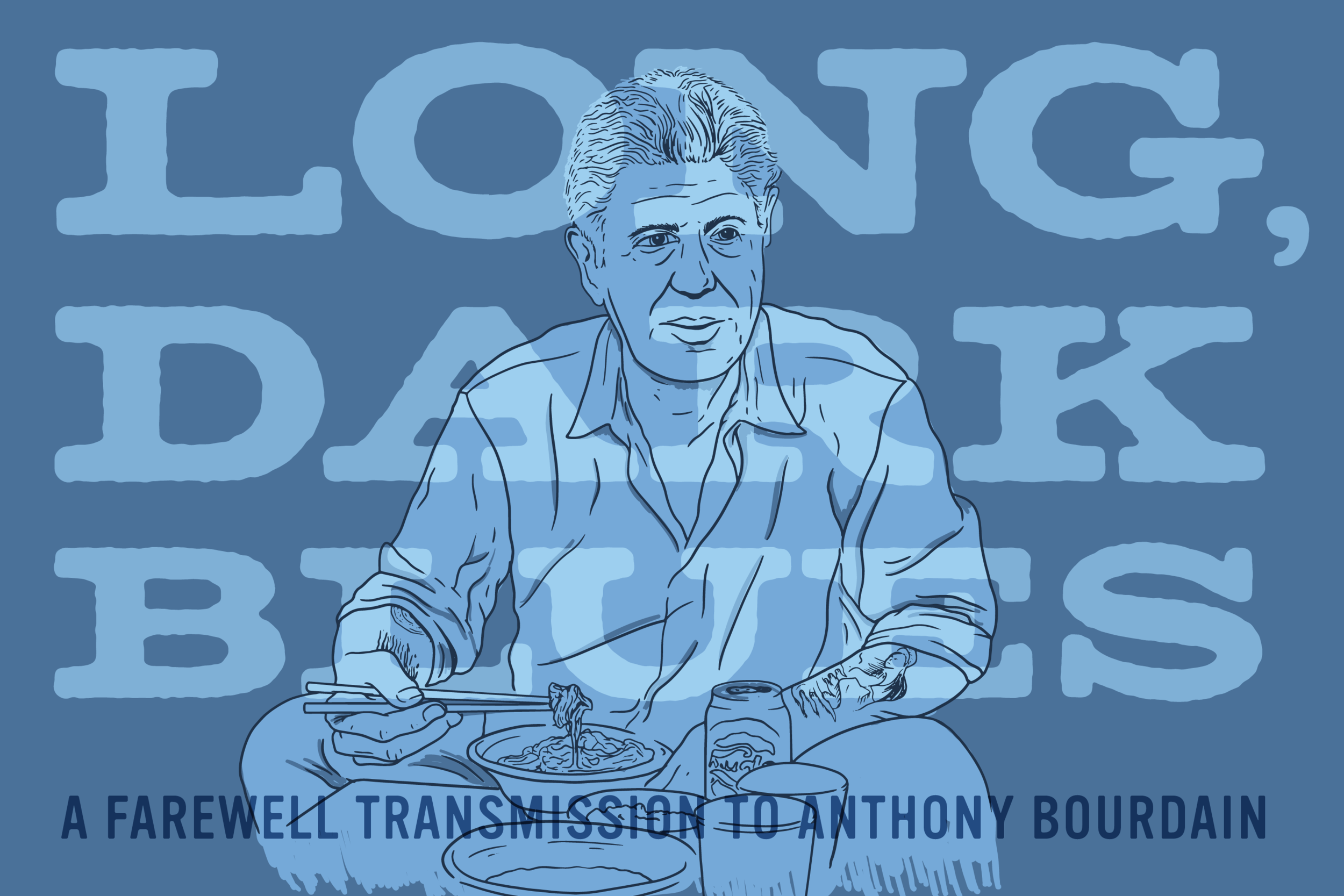

Written by

Written by The GBH Collective