There’s an unsettling disquiet in the wake. Something happened here.

The sidewalks are vacant. January isn’t the high tourist season anyway. It’s too rainy and the northward-drifting fog is an unwelcome photo subject. But the devastating wine country fires last October left a daunting recovery task for Santa Rosa.

The refuge is the Russian River Brewing Company.

“It’s gonna be a while for a table, but the bar’s open,” the host offers as I reach the front of the queue.

Unlike most businesses downtown, people have returned in droves to this brewpub. Glances dart around the bar, as locals and tourists prepare to pounce at a vacant seat. Dozens of World Beer Cup and Great American Beer Festival medals fastened inside dusty frames above the bar gaze down at patrons; underneath them is an array of soured and fresh beers listed out on a menu, fairly legendary names in the beer world just kind of humbly hanging out:

Pliny the Elder. Blind Pig. STS. Supplication. Consecration. Damnation. Sanctification.

It’s the neighborhood pub here, where hometown folks unbothered by the crowds swing by to grab cases of Pliny for their weekend barbecues. But it’s also a beer mecca, where Russian River’s founders, Vinnie and Natalie Cilurzo, readily pour beers for local residents just as often as for the excitable, starry-eyed obsessives looking for "_____tion" beers on their very first 4th Street pilgrimage.

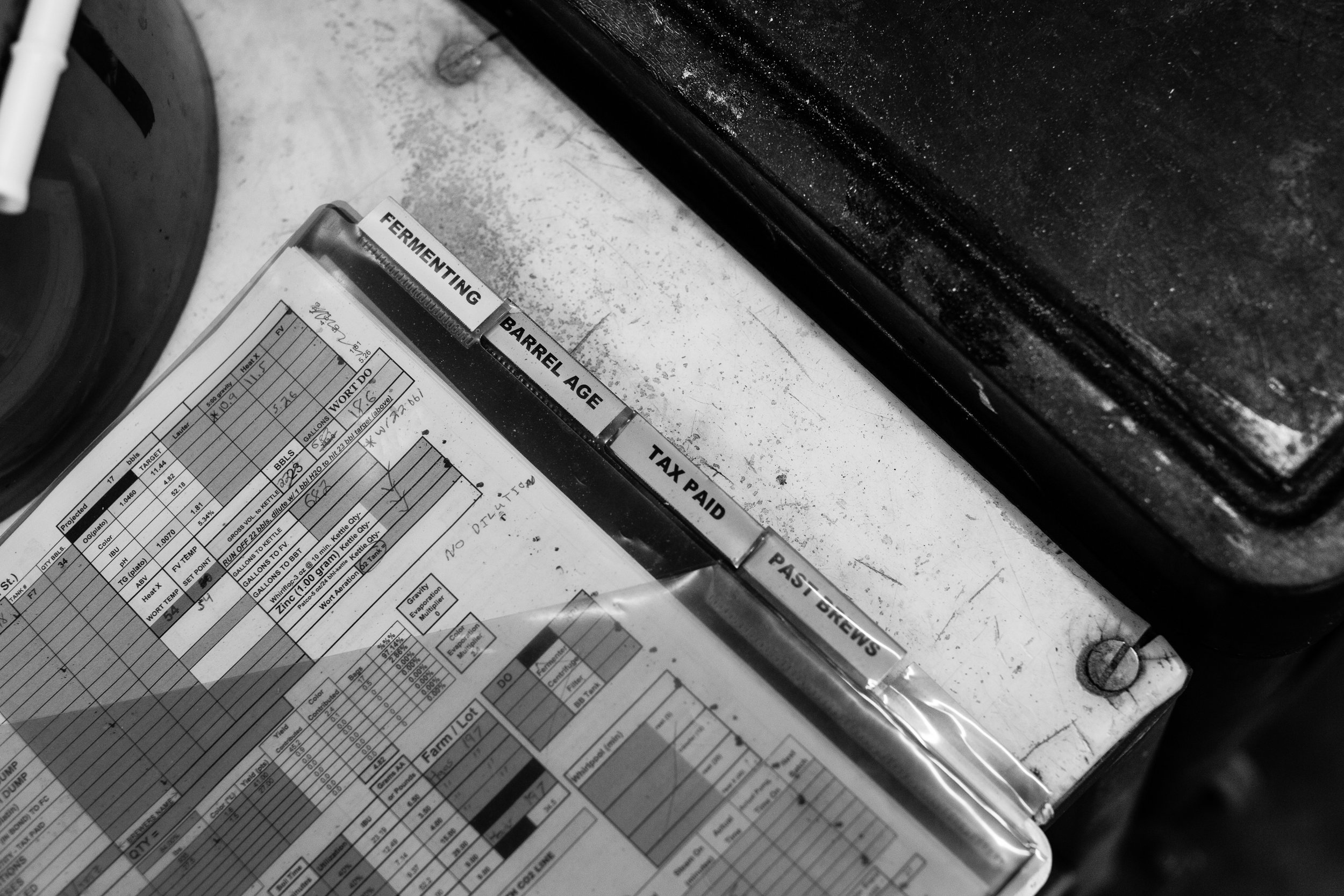

A few miles away is their compact brewhouse, tucked in a quiet, nondescript business park. Bottles rattle down the line as two men package Pliny the Elder. Soon the beers will be placed into folded green boxes and sent off to carefully-selected retailers.

This isn’t Russian River’s first brewing system, Natalie explains as we walk into her office with Vinnie. This one replaced one they bought from their friend Sam Calagione years ago. But before that, even before Russian River, all they had was an even more rudimentary system.

“I bought a 7-barrel system from a guy that was in jail in Arizona for selling marijuana mail-order,” Vinnie deadpans in Natalie’s office, referring to his first commercial brewing system. “I’m almost not sure you could get arrested for that now.” He pauses. “It’s still a felony, but they’d look at you a little differently. They’d say it’s not even worth it.”

Natalie’s clicking through old photos on her desktop screen, providing vignettes to Vinnie’s oral history. The two are, to many, mononymous in the industry, and their anecdotes now amount to a beer folktale to friends and fans. But for younger peers their story is an exemplum, pointing toward the merits of the thoughtful business plan the Cilurzos have forever embraced:

“Slow growth, organic, grow when it feels right,” Vinnie says.

“I bought a 7-barrel system from a guy that was in jail in Arizona for selling marijuana mail-order. I’m almost not sure you could get arrested for that now.”

Long before they helped turn Northern California into the world-famous beer-making region it is today, there was just a cheap brewing system Vinnie bought from a pot-dealing acquaintance in Bisbee, Arizona. Everybody called him “Electric Dave.”

Electric Dave sold Vinnie an old soup vessel for a brewing kettle, a DIY mash tun, and plastic fermenters before he and Natalie—who, at the time, was working full-time at a winery—opened Blind Pig in Temecula in 1994. The equipment, as Vinnie generously describes it, was “pretty rough,” but it was sufficient enough. After rigging it up, they learned how to work with it well enough to impress influential homebrewing author George Fix, who one year had attended a Southern California beer festival hosted by Vinnie’s parents’ winery.

“We got George out to speak and he tasted some of our beers,” Vinnie recalls. “He was blown away that this beer could be made and it was that good in plastic fermenters. He wrote about it once, and it was a feather in our cap.”

In fact, it was through winery connections that she and Vinnie met years earlier. Natalie, a late teen at the time, was working for a winery called Piconi. One day, she and her employer had driven over to Cilurzo Winery—owned by Vinnie’s parents—to buy some produce when she saw Vinnie crushing grapes. The two were introduced that day, but it wasn’t until they found themselves at the same party the next summer that they started talking and Vinnie invited her to his 20th birthday.

At the time, he was a homebrewer messing around in his parents’ winery’s drain- and hose-equipped cellar. When they started dating, he found himself with company—Natalie would spend up to three or four nights a week there, talking while brewing and bottling. She brought the Scarcella’s Pizza and, because she was of legal drinking age and Vinnie wasn’t, the beer.

Opening a brewery was always the goal, and in 1994, they made it happen—for a while. It did not go very well, but it wasn’t entirely fruitless. “Our first beer at Blind Pig was the Inaugural Ale, which is now supposedly the first double IPA,” Vinnie says.

The brewery, an anomaly then, could barely sell IPAs, let alone a double IPA, to bars in (of all places) San Diego. “It had a small following, but to think back then to look forward now and say IPAs are the top-selling craft beer—it would have been impossible to believe,” Vinnie says. “People were like, ‘This is bitter!’ They didn’t like it.”

Asked to put tasting notes to the admittedly unbalanced Inaugural Ale, Vinnie describes the taste of the relative monstrosity as comparable to “licking the rust off a tin can.” It was aged on American oak chips because, as a winemaker, he believed the tannins from them would contribute astringency and dryness to the beer. He was right, too. Too right, even—it proved excessively bitter. And then he one-upped himself by double dry-hopping it, too.

“I think we were the first to do that,” he says of the two dry hop additions, cracking a sort of “smh” grin at his younger self. “But at the time, I didn’t know why you would do that.”

Natalie, looking through pictures of the early Blind Pig days, comes across one of Vinnie holding a huge bag of hops. He looks stoned, she jokes. Vinnie smiles. “That was the year I decided to take 10 pounds of wet hops and rip every cone open so that there’d be more hops exposed,” he says. “For hours I sat in the cold box. I thought it would be a great idea to shred open 10 pounds of hops.”

He pauses. “Did it work?” I ask.

“No,” he replies flatly. “Too grassy. It was the worst idea ever. There is such a thing as too much hops.”

“I asked all my friends who own big breweries, and they all said ‘I stopped having fun at 50-60,000 barrels.”

Vinnie’s methods proved too ahead of the curve, and Blind Pig hit financial trouble. He’d seen his parents work themselves hard at their winery (in addition to his father’s job as an Emmy-winning lighting director for Merv Griffin), and didn’t want to see his career become equally demanding. But after three years, it didn’t look like Blind Pig’s business would improve, so the two, by now married, sold his stake in the company and drove north.

“We moved up here with no jobs,” he says. “We had one car, we had three or four thousand dollars in the bank, had no place to live. [We] put everything in a storage unit and moved in with a friend in Cloverdale. [Natalie] started looking at winery jobs, and I had a lead at Korbel, but they hadn’t officially hired me. I hadn’t even interviewed with them.”

Natalie, with an already impressive résumé in wine, found a job quickly. Vinnie also lined up two job offers. One was with Benzinger Family Winery, which had decided to open a brewery they were calling Sonoma Mountain. It had the job security going for it, at least. Benzinger offered a full-time position, but Vinnie would have had to make primarily Lagers. “Not really Vinnie’s thing,” Natalie says, so he went with his other offer from Korbel Champagne Cellars.

“Microbreweries were having a renaissance at the same time Korbel was building a delicatessen and market in 1995-1996,” says Gary Heck, who serves as the longtime president and owner of F. Korbel and Bros. “When it came time to decide what beer we should serve and sell in our deli, we decided to produce our own. Being located on the Russian River, we decided to call the beer Russian River Brewing Company.”

Heck remembers Vinnie as being “very knowledgeable” about beer, and said they hired him for the gig because he “seemed like a perfect fit having come from a wine family in Temecula.”

Sonoma Mountain, as it happened, folded almost immediately. “Talk about one of those decisions that affects the rest of your life,” Natalie says. “What you think is not a big decision at the time can end up changing your life.”

Though he had already won a few Great American Beer Festival medals with Blind Pig, Vinnie piled on those, and brought home more for his work with Russian River, including the prestigious "Small Brewing Company of the Year" and "Small Brewing Company Brewmaster of the Year" in 1999. As Heck recalls, the honors were proof that he was onto something.

“Vinnie could make an excellent product,” he remembers.

A year later, Vic Kralj, influential owner of the The Bistro in Hayward and eventual co-founder of what became San Francisco Beer Week, presented Vinnie with a challenge: Make the best double IPA in the Bay and bring it to their new festival, 15 miles south of Oakland.

Kralj explains that he and his friend had noticed local brewers experimenting with Double IPAs. The Bistro already had an IPA fest, but Kralj thought, why not a Double IPA competition too? You might say the man was a little ahead of his time.

Kralj called up about a dozen breweries, including Russian River, to gauge interest, and Vinnie was game. As Kralj remembers, “[He] came out with this name, Pliny the Elder, and I said, ‘What the hell is that?’” Pliny, Vinnie explained to him, is probably the guy responsible for giving that important plant—the hop—its Latin name, Lupus Salictarius. Kralj loves that story, and the beer too, adding that “that first year, I thought it’s a good beer. It’s a great beer.”

Now, 18 years later, he says Pliny is still his best-selling beer, and praises it as “the quintessential double IPA, so well-balanced, so easy to drink, but with alcohol in it.” He doesn’t remember if Russian River took gold that year, but says that, over the years for the fest (which now brings in over 100 brewers), Pliny has won several times.

But back in 2003, for all the hardware and acclaim Russian River was earning, it wasn’t enough to keep the experimental operation running. That year, Korbel followed financial advice to shutter the brewery. The company offered Vinnie a winemaking job, with benefits and potentially up to six figures in annual salary, but he’d already been mulling an alternative plan.

“He came home and said, ‘What should I do?’” Natalie says. “I was like, I’ve never known anyone as passionate about doing one thing as you, so I said, ‘I think you need to go back and negotiate for the brand, and I’ll quit my job and we’ll do this. Let’s do this.’”

A week later, Vinnie took his negotiations to Korbel and, in lieu of a severance, took the company name and beers the company had become famous for, including Damnation, Temptation, Salvation, and Pliny the Elder.

“We gave Vinnie a good deal on the name,” Heck says.

After almost exactly a year of fundraising, the Cilurzos opened their downtown Santa Rosa brewpub. It was actually two properties, together totaling 7,100 square feet, and it required serious labor to take it from an old, carpeted English pub to what would become a small brewhouse and taproom. They didn’t have the cash to hire contractors, so they DIY’d the space themselves. Vinnie jackhammered the floor, and they fashioned tables out of bowling lanes.

But the plan was moving. Then-Kendall-Jackson CEO Lew Platt, who Natalie had previously worked for, helped pen their business plan (and, subsequently, became their first investor), and about 30 family members and former co-workers followed suit, investing a total of $850,000 to get the now independent Russian River off the ground. The Cilurzos brought on two people to run a food program (“In the end, it was the best decision to open a restaurant,” Vinnie recalls.), and by the next year, they were already buying back equity.

“I thought it would be a great idea to shred open 10 pounds of hops. It was the worst idea ever. There is such a thing as too much hops.”

One unassuming February morning in 2010, Vinnie saw people lined up outside the brewhouse on his way in. Perplexed by the crowd, he singled out someone in line to ask what was going on. Pliny the Younger, Russian River’s soon-to-be storied Triple IPA, was ranked No. 2 in the world on RateBeer and BeerAdvocate.

Vinnie had never heard of either.

In any case, it was a bad day for a business boom. He was so sick that night he began coughing up blood and had to visit the emergency room. Natalie was nursing a recent knee surgery. Unable to move around easily, she leaned up against the counter to fill growlers of Younger—something they’d never again do after this day—and ended up soaked in Triple IPA.

“Everybody had PTSD,” she says, eyes widening. “It was a horrible day.”

They had given “the worst” customer service and their kitchen couldn’t keep up with the orders. They ran out of Younger in eight hours.

“I got to the brewery not long after they opened on the official release day,” remembers Ryan McKay, a patron who visited Santa Rosa for the event. “In contrast to the night before, it was already quite busy, and grew exponentially crowded and noisy by the hour. I would agree that it seemed like the staff weren't really prepared for the number of people that showed up.”

McKay says that despite the crowd, he did get to try the beer pretty quickly and bring home growlers of it too, but when he came back later with a friend, the line was “out the door and far down the block.” (Of the more than 1,100 beers McKay has rated on BeerAdvocate, Younger is the third-highest beer he’s ever had, just a pinch behind Russian River’s Supplication.)

Meanwhile, Natalie, exhausted after the day, sought refuge at a steakhouse with a friend to decompress. She ordered a dirty martini. By the time it arrived, she was gripping the bar. “I (was) like, ‘If I could drink this without touching the glass, I would. Like if I could drink this like a cat right now, I’m so tired, I would probably do that.’”

Years later, the Younger release is now a meticulously orchestrated event. The Cilurzos spend thousands of dollars on extra security, customized stamps, city event permits (necessary for lines that stretch the block), and branded wristbands featuring their logo and three pull tabs—one for each pour of Younger a guest is allowed to buy.

A lot of extra money is also thrown at Younger on the production side. It’s a more stunted yield. Where a normal batch of Russian River beer will produce 16 barrels, Younger only makes 12, due to the excessive hops used.

“I got to the brewery not long after they opened on the official release day. It seemed like the staff weren’t really prepared for the number of people that showed up.”

But despite the upfront cost, Younger’s ROI is worth the hassle, and not just for the brewery. The annual two-week release event has become so lucrative for the brewery’s surrounding hotels and restaurants that Sonoma County has twice measured the economic impact of the Pliny the Younger release. In 2013, the release’s 12,500 attendees from mostly outside Sonoma County generated $2.36 million for the region. Just three years later, the amount earned for the area shot up to $4.88 million. Around 16,000 people came from around California, the country, and the world, from as far off as Japan, Spain, and Brazil. All for three small pours of a world-famous Triple IPA.

“It was quite the increase since 2013, but it does reflect what the economy is doing,” says Francesca Schott, Business Services Coordinator for Sonoma County. Schott says that the bounce back from the recession has helped draw consumers to spend money at such an event, and that the county also honed its measuring tactics in the meantime.

“By 2016 we were in a very strong economy,” she adds. “To see that almost doubling of the economic impact shows the strength of the Russian River brand and their commitment to consistency and maintaining what consumers love about that product.”

It was going to be business as usual in the preparation for the 2018 Younger release, but on the evening of October 8, 2017, around the time Russian River would start to shift around beer production plans to brew Younger, everything changed. Vinnie and Natalie had just arrived home from the Great American Beer Festival in Denver, but Natalie couldn’t sleep—she kept waking to the smell of smoke. She’d seen on the news earlier that flames were flaring near Calistoga, but being high fire season in California at the time, it didn’t seem immediately dangerous.

But at 4 a.m. she awoke again to Vinnie already sitting up in bed, alarmed. They turned on the news to see that the "smoke and ash and wind and terror" had spread to Santa Rosa.

The city’s Coffey Park neighborhood was leveled. More than 40 people died as a result of fires that blazed across 250 square miles (equal to more than five times the size of San Francisco), and Santa Rosa residents alone lost 3,000 homes.

Their house, their brewpub, and the new brewhouse under construction in Windsor, up the road, were fine, but at the time they were primarily worried about their staff. Some of their employees lost their homes. Some of their fellow brewers fled burning homes, too. Their good friend Brian Hunt, who founded Moonlight Brewing and has fire-fighting training, headed toward danger and personally butted out new flames with a shovel and nearby garden hoses.

Natalie and Vinnie mobilized, and began dialing their lawyers to devise a recovery fundraising plan. What they came up with was two-fold: First, they contacted dozens of breweries, maltsters, and hop growers they were friendly with to ask for donated time, resources, packaging, and selling power to help them raise money under a license they owned called “Sonoma Pride.” It wasn’t long before word spread and breweries started calling them. By the end of the campaign, more than 60 beer makers, some as far off as the UK’s Beavertown and Florida’s Cigar City, were producing Sonoma Pride brews.

The second part of the plan was difficult to execute: hold a raffle to skip the famously hours-long line for the Pliny the Younger release. One winner, Natalie says, was a local and opted to donate his prize to a firefighter whose kids lost all three of their homes—the firefighter’s home, his ex-wife’s, and his girlfriend’s—while he was battling flames.

“I told him he could bring three guests and I’m not going to let them pay for a thing,” Natalie says.

The raffle, which they had to cut off, raised $114,000, but the fundraiser as a whole brought in a million dollars and counting. And yet, for all the good work, and recovery efforts underway in Santa Rosa, Vinnie isn’t convinced it will be enough to attract folks back to the area.

“It’s like Natalie says, the two things we can’t predict are the weather and how many people show up [for Younger],” he says. “This could be the year that with everything that’s happened—the fires, tourism is down, 5,000 families [across the region] have lost their homes and they don’t have friends coming—we just don’t know. But we’ve always approached it from a very cautious side, [and] our staff doesn’t take it for granted.

Russian River’s brewpub has always had one strict rule: “Our hours are our hours.” Sonoma County is, and it has been, back in business, ready for tourism to pick back up. Now, they’re just waiting for everyone to return.

One way to revive beer tourism in the area may be a brand new facility that the Cilurzos are literally building from below the ground up. A massive brewhouse set to open in nearby Windsor, Calif. will allow them to produce up to 70,000 BBLs—a big jump from their current 17,000 BBLs—if they want. And only if they want.

“I asked all my friends who own big breweries, and they all said ‘I stopped having fun at 50-60,000 BBLs,’” Natalie says. “We don’t play the [distribution] game—don’t play it well. We like to operate in our own way. We like retail, we can drive people to our brewery, to pay the bills, pay our employees well. That’s what we’re going to do.”

The new space will be a tourist destination with a restaurant, the pair say. Built with the intention of giving longtime fans an inside look at how they brew their beer, the brewhouse will offer free and paid tours—something they’ve never done before—that take guests down the “spine” of the brewery to the “brewhouse, lab, yeast, open-top fermenters, regular fermenters, packaging, and funky at the end.” The point of organizing the brewhouse in that way was, as Vinnie says, “so we could tell the story of how beer is made and not jump around.”

He’s even half-seriously thought about dedicating a portion of the new brewhouse to one of their early mentors and good friends, adding, “I jokingly said there’s going to be a whole wing of this brewery dedicated to Ken Grossman and his team [at Sierra Nevada].”

It’s a massive undertaking, not made easier with the Sonoma Pride campaign and Natalie’s recent re-election to the board of the California Craft Brewers Association, but they don’t seem too worried about having long to-do lists.

“We’re unusually busy people,” she says. “A lot of people don’t work all day, every day, but I feel like this is all we know how to do. We got used to the pace.”

It may be that keeping that pace, and even struggling, is an important component of the Russian River model for success, too.

“I wonder about the small brewery that didn’t suffer, that didn’t go through the tough times,” Vinnie says. “I think the difficult times make you strong.”