“No. They didn’t.”

I’ve said this with the confidence of someone who was there sweltering in the Virginia sun two centuries ago, feeling hard-packed Virginia clay under the soles of my bare feet gone soft and powdery with generations of tread. I was not there. But I didn’t have to be. What historians and archeologists have discovered about the social and economic hierarchies of nineteenth-century plantation estates in the American South is enough to draw the reasonable conclusion that none of the founding fathers actually brewed his own beer.

This nugget of pop-history has enjoyed uncommon longevity, which is somewhat surprising considering how many truly excellent beer histories have been penned in recent years. Somewhat surprising. History is a composite sketch, rendered by skillful analysis of the accidents of time and physical preservation and the lasting traces of social privilege. For better and for worse, history is most generous to the “haves.” Those with fame and power, or simply enough material wealth to leave some behind, have been given the tools with which to craft their own stories.

Brewing beer is hard, messy work, even today with the benefits of advanced instrumentation, mechanization, automation, and refrigeration. In the colonial era, brewing was a combination of agricultural alchemy, grueling cookery, and brute manual labor. Those to whom antebellum history has been kindest almost certainly “delegated” this kind of labor. Of course, I was not there, so I can’t speak with absolute certainty. But I have as much trouble conjuring the image of one of the architects of the Constitution tending a mash as I have imaging John Adams delicately placing lattices of dough atop mince pies in preparation for the holidays, or picturing George Washington bent over to sow tobacco seed in the fields at Mount Vernon, or visualizing James Madison rhythmically scrubbing someone else’s sweat-soaked woolens on a washboard, or envisioning Thomas Jefferson swinging a scythe to bring in the wheat harvests from the rolling hills that surround Monticello.

I was not there, but my ancestors could have been. And since I first began to research the American brewing industry almost a decade ago, I have suspected there’s a robust, undocumented brewing tradition among enslaved Americans. Having recently carved out time to pursue this question, I went to the most logical place in search of answers—Thomas Jefferson’s house.

It was the kind of spring day that invites you to think about the past and that makes present day concerns—the amount of dust kicked up on the winding gravel drive approaching Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest, for instance—seem petty and anachronistic. It was breezy, the sun was shining, the Blue Ridge Mountains shimmered azure in the distance, and I’d just washed my car.

The curtilage on the 4,819-acre plantation is demarcated by the same style of split-rail fence that snakes across the grounds of the Manassas National Battlefield Park, where, on annual elementary school field trips, I became deeply confused about whether the confederates were the good guys or the bad guys. This trip inspired similar ambivalence.

The octagonal dwelling house, an hour or so southwest of Monticello, wasn’t merely a vacation home, but a residence used during all four of Virginia’s distinct seasons, a working plantation that was an important financial contributor to the estate, and a safe haven for the family when Thomas Jefferson was pursued by the British in 1781.

Jefferson retreated from the commotion of Monticello to his private home at Poplar Forest more frequently as he approached retirement from public office at age 65, when he wrote, “Never did a prisoner, released from his chains, feel such relief as I shall on shaking off the shackles of power.” In the relative solitude that Poplar Forest provided, he pursued his passions for reading, writing, studying, and landscape gardening, while as many as 94 enslaved men, women, and children lived and worked on the plantation grounds.

Sheepishly, I asked if I could touch a ceramic bottle displayed in the front window of the Archaeology Building, where the facility's library—my eventual destination—was housed. The bottle was nearly two thirds-complete and laced with cracks that defined the edges of each of the fragments that were individually excavated by the archeologists on staff. In retrospect, I should have seen the metaphorical equivalence between this beer bottle, heavy and incomplete in my hands, and the research project that brought me to Jefferson’s home and grounds. But it passed, and after meeting the library staff, I settled in at a table in a small-but-packed library in the Archeology Building’s converted attic. Page by page, I read, growing more fascinated and frustrated over the hours, as the dynamic between Jefferson and a slave named Hemings unfolded.

The Sally Hemings Room at Monticello opened to the public on Saturday, June 16, 2018, more than three weeks after my first visit to Poplar Forest in search of information about beer brewing on Jefferson’s estates. The New York Times reported that the exhibit’s opening dealt a “final blow to two centuries of ignoring, playing down or covering up what amounted to an open secret during Jefferson’s life.” The ‘secret’ was his relationship with Sally Hemings, a woman he enslaved and with whom he fathered three children. Jefferson’s sordid history with his wife’s half sister (according to most historical accounts, Sally Heming’s father was John Wayles, Jefferson’s father-in-law) is no doubt the main attraction among Monticello’s new exhibits. But another exhibit—a restoration of the earliest kitchen at Monticello, where Sally’s younger brother Peter Hemings cooked—is more relevant to the history I hoped to recover.

The archaeological record reveals that enslaved people distilled brandies and other spirits on site, both at Monticello and Poplar Forest. But prior to 1812, it appears that beer was primarily purchased along with French wine to be served at table. Jefferson’s letters are sprinkled with records of transactions like this one:

“1790 June 16 - (New York) Farquhar 1 dz. Bottles Porter 20/ (MB).”

In 1812, Captain Joseph Miller visited Monticello and was detained for an extended of period time due to the war with the British. In the intricate colonial economy of favors among men of influence, Miller, formerly a London-based brewer and maltster, agreed to train Peter Hemings in the arts of both malting and brewing.

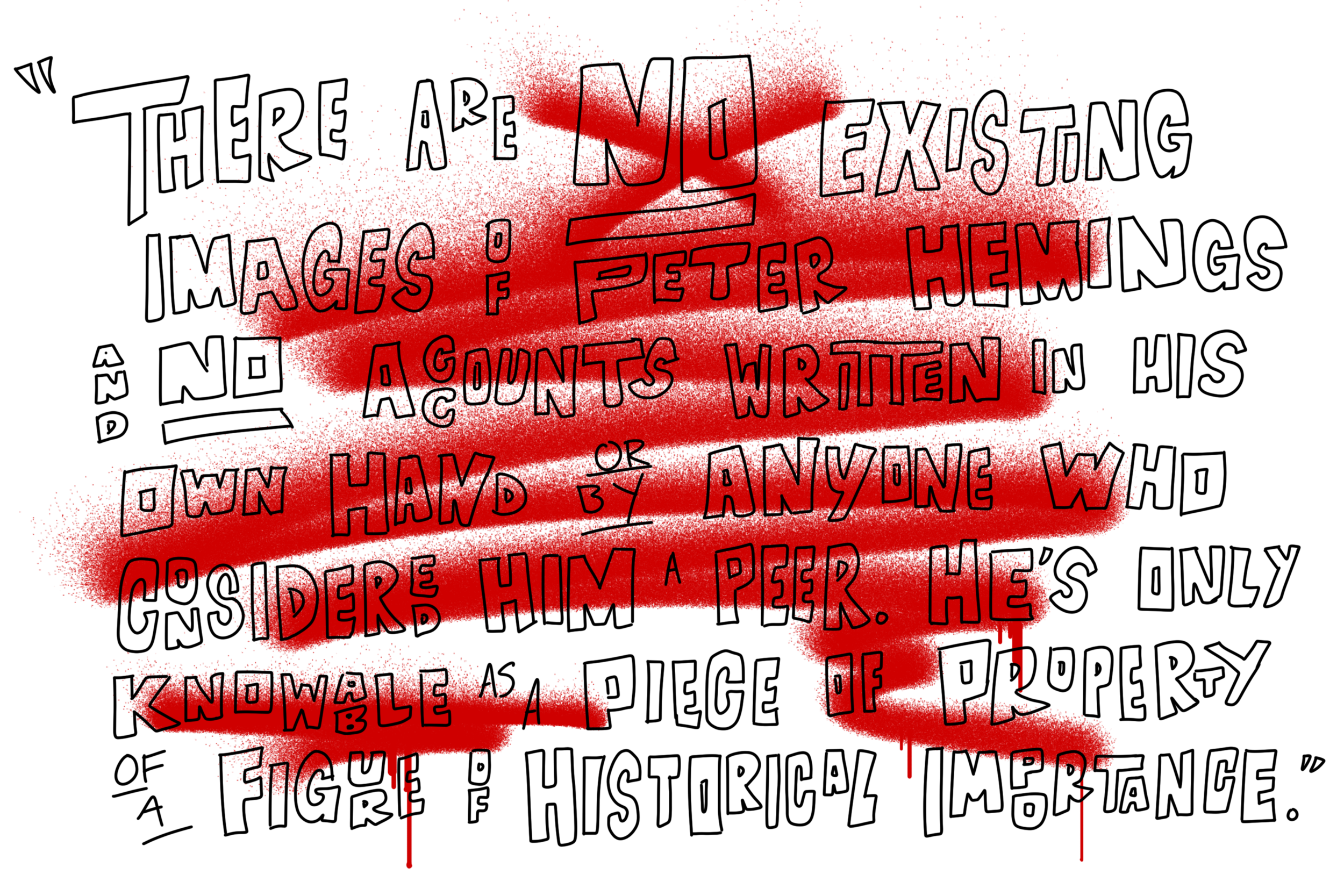

There are no existing images of Peter Hemings (nor of his more famous older sister) and no accounts written in his own hand or by anyone who might have considered him a peer. Peter Hemings is only knowable as the valued piece of property of a figure of historical importance. His accomplishments are given by the processes of history-making to Thomas Jefferson, who on April 25, 1815 wrote, “I am lately become a brewer for family use, having had the benefit of instruction to one of my people by an English brewer of the first order.”

Though overseen by Jefferson, “Peter must have had some latitude with the brewing process,” according to Jack Gary, Director of Archaeology and Landscapes at Thomas Jefferson's Poplar Forest.

On June 26, 1815, Jefferson wrote to Miller a few years after he trained Peter Hemings, “Our brewing of the last autumn is generally good, altho’ not as rich as that of the preceding year, the batch which Peter Hemings did for Mr. Bankhead was good, and the brewing of corn which he did here after your departure would have been good, but that he spoiled it with over-hopping.”

“The question is,” Gary mused, “did Peter actually spoil it, was he trying something new, or was he brewing to his tastes?”

Jefferson’s records reveal that barley was not grown on either of his properties and what recipes for beer have been recorded feature wheat-dominant grists. I imagined the cloudy, aggressively-hopped beer that Hemings may have “spoiled,” and wondered if perhaps he was a visionary, brewing 200 years ahead of his time.

“Regardless, he was the one doing the work,” Gary continued. “Just like cooking for white families where African-American cooks certainly added their own spices and contributions to meals, it was probably also happening with brewing.”

With several years of experience, Peter Hemings came into his own as a maltster and brewer, and may have taught these trades to other enslaved men in Virginia. On April 11, 1820, Thomas Jefferson wrote to James Madison, “Our brewing for the use of the present year has been some time over. About the last of Oct. or beginning of Nov. we begin for the ensuing year and malt and brew three, 60-gallon casks successively which will give so many successive lessons to the person you send… I will give you notice in the fall when we are to commence malting and our malter and brewer is uncommonly intelligent and capable of giving instruction if your pupil is as ready at comprehending it.”

What is clear and difficult to reconcile is Jefferson’s obvious recognition of Hemings’ talent. In 1821, James Barbour (former U.S. Senator, U.S. Secretary of War, Virginia Governor, and namesake of Barboursville, VA) wrote to Jefferson, asking for a recipe for the ale he drank during one of his visits to Monticello. Jefferson replied, “I have no receipt for brewing, and I much doubt if the operations of malting and brewing could be successfully performed from a receipt. A Captain Miller now of Norfolk...he had been a brewer in London, and undertook to teach both processes to a servt. of mine, which during his stay here and one or two visits afterwards in the brewing season, he did with entire success. I happened to have a servant of great intelligence and diligence both of which are necessary.”

Dr. Kelley Fanto Deetz, historian and author of Bound to the Fire: How Virginia’s Enslaved Cooks Helped Invent American Cuisine, suggests that Jefferson wasn’t alone in recognizing the talent and cultural ability of the people enslaved in colonial Virginia. She says an appreciation of the cultural contributions of enslaved African-Americans was widespread—found, for example, in letters from mistresses to one another, and that slave-owning families benefited so much from enslaved labor that “the convenience of slavery outweighed the morality of condemning it.”

We do not have enough of the necessary ingredients to create a satisfactory history of Peter Hemings, principal cook and brewmaster for one of America’s founding fathers. Chances are, the same is true of Peter’s contemporaries. We will, through the accidents of time and physical preservation, inevitably know more about the spaces in which they brewed, the tools with which they worked, and the recipes they must have memorized and adapted. Deetz characterizes the process of recovering such histories as filled with “constant frustration and occasional reward. Enslaved people’s stories are hidden in recipes, in the architecture, in letters, diaries, and financial records of their enslavers. Evidence of their talent and skills were consumed both literally and figuratively by the ones who enslaved them.”

After Thomas Jefferson's death in 1826, Hemings was purchased by one of Jefferson’s relatives and eventually given his freedom. We know little of Hemings’ life as a free man. He worked as a tailor in Charlottesville and died sometime after 1834.

As I reflect on Peter’s life and brewing career and on the laborious task of making histories from “negative space,” Brian Albert’s recent argument for historical preservation in the craft brewing industry resonates in a newer, simpler way. Documenting the evolution of the industry, its business practices and engagement with communities, its legal and regulatory battles, and its stories of success and achievement—this is all crucial to the service of history.

But a simpler declaration might be most important: As craft beer continues to grow, let brewing men and women from every background imaginable state clearly, and for the record, “We were here.”