“If Americans eat shit, we would do it, too.”

This is something I was told last year by a German friend who was born—and has spent his whole life—in the Deutschland, noting an attitude of reverence from his countrymen and women over the past decade. An odd piece of anecdotal, culinary-based trivia, but it’s enlightening all the same.

The idea of American exceptionalism as the predominant force in an ever-globalized world seems outdated, even if still true in certain ways. You can bleed all the red, white, and blue you want, but it doesn’t change the fact that clout now comes from all over, at rapid speeds and rates of success, like never before. The internet, cheap travel, and plain-old human curiosity have increased the rate at which cultural diffusion weaves people and systems together, creating connections that never would have existed even a decade ago.

But America’s near-stranglehold on pop culture and worldwide trends hasn’t fully diminished. Just because the playing field has become more even, doesn’t mean the U.S. is any less talented in terms of accelerating ideas that become phenomena. It’d be safe to say Vegas wouldn’t place as favorable odds on other countries changing the way Germans source their food.

No matter how many walls—virtual or real—are broken down for the sake of shared international authority, the sheer inertia created by American ingenuity is still hard to avoid, its pull constantly bringing many toward its orbit. When it comes to beer, that universe is ever-expanding with no signs of slowing down.

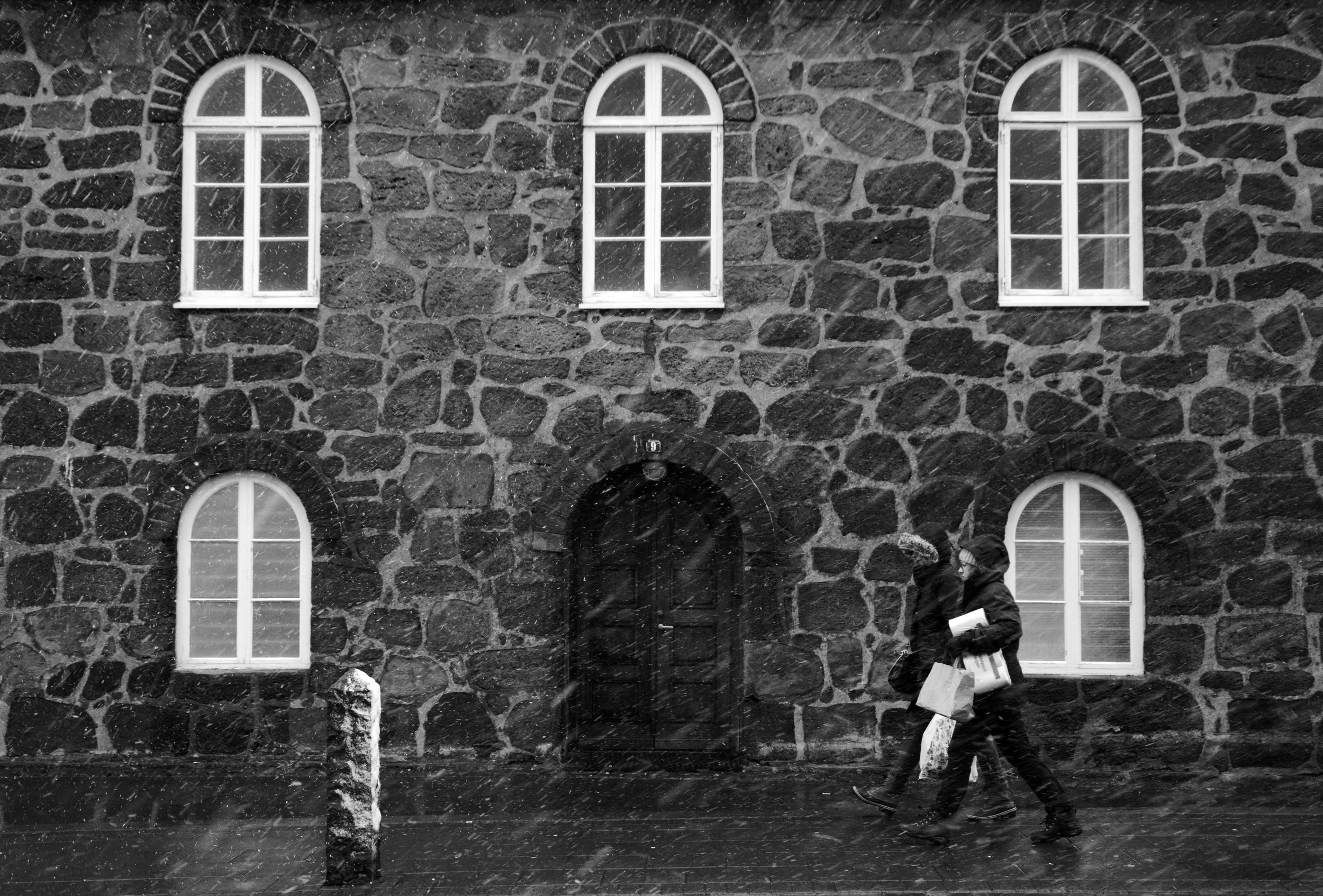

Iceland in February possesses a multitude of personalities. A schizophrenic climate delivers thunderous snowfalls that pile thick flakes on sidewalks and streets, only to be melted away by warming rays of an afternoon sun just hours later. As a visitor, it’s hard to pinpoint if you should be sheltering indoors by a radiator that’s spewing warmth from the country’s geothermal power sources or heading out in the right combination of layers that you’ll inevitably shed to enjoy a sun-drenched moment outside.

It’s enough to make you want to hunker down with a rich, chocolatey Stout, only to immediately question that decision, pivot, and sit in a sunbeam with a bright, bitter IPA. In theory, the drinking options could easily reflect the climate: malleable.

“We have a saying here: ‘if you don’t like the weather, just wait a minute,’” says Hinrik Carls Ellertsson, a Reykjavik resident and brewer with KEX Brewing. “We have to be on our toes all the time.”

From an outside perspective, the situation seems perfect for enjoying an array of beer. Not only does the weather encourage a near hourly question of what style may feel most appropriate in that moment, but the dining options do the same. Fish is everywhere, prepared smoked, fried, or fresh, and accompanied by rich sauces that are both spicy and sweet. The light meat calls for something hoppy and crisp, the flavorful gravies pair nicely with the depths of dark malts.

But beer in Iceland, like every other country on Earth, is led by Lager. Viking Ölgerd’s Viking Classic (a Vienna-style Lager), Bruggsmiðjan Kaldi Lager (a Czech Pilsner), and Borg Brugghús Brio (a German Pilsner) are easy to find. Einstock, the most popular craft brewer in the country, added a Blue Moon-like boost to flavor options when it started in 2011, its Belgian wit a mainstay in bars and restaurants.

If local enthusiasts have their way, however, the future will have a distinctive American taste.

“I only drink IPA,” a bearded Reykjavik resident tells me while sipping a mango-infused Pale Ale that would look more at home in New England than Iceland.

“I love IPA,” agrees Ellie, a Latvian who left her home country in 2014. She came to Reykjavik to seek new opportunities and, in taste, found comfort in American hops. Her boyfriend, Kaspars, typically avoids the hoppy stuff, but can’t refill a glass quickly enough with Kindred Spirits, a lacto IPA made by Denmark’s Alefarm Brewing.

Like me, they’re spending time in the downtown of Iceland’s capital as part of an annual celebration that marks the end of the country’s prohibition, which concluded a 74-year ban of “strong” beer above 2.25% ABV in 1989. Wine and spirits had been reinstated more than 50 years prior, but the decades in between continued to dismiss beer as a low-cost alternative that might only act as a catalyst to spur addiction.

Once again legalized nearly 30 years ago, beer began its slow, deliberate crawl toward a craft-focused modernity. Like so many other places scattered across the world, whether with their own beer history and traditions or not, the greatest influence on how to play catch up has most commonly come from America, where brewing rules were made to be broken, styles exist to be mashed up and, above all other ingredients, hops rule supreme for the vast majority of breweries.

“Our market is small, the brewers are few, so there aren’t that many people to learn from,” says Árni Theodór Long, brewmaster at Reykjavik’s Borg Brugghús. “We have to get our learning from somewhere else, and it definitely helps when we get the American and experienced European brewers here.”

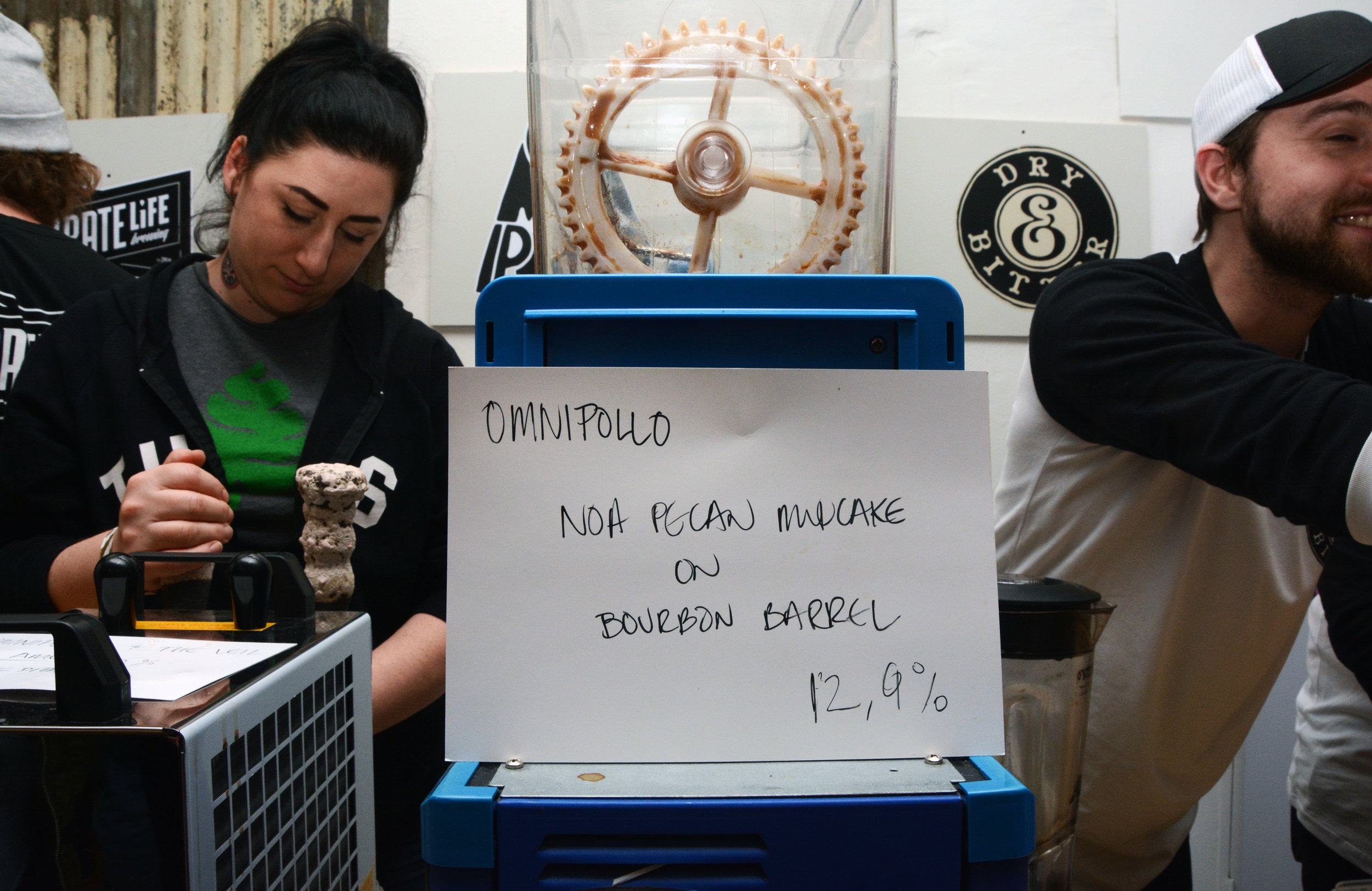

For a country of roughly 330,000, where its beer industry is still in its infancy, there’s no greater concentration of brainstrust than at the Icelandic Beer Festival. In 2017, a record number of international breweries included American hop purveyors Boneyard Beer, Founders Brewing, Stone Brewing, Other Half, and Aslin Beer, the latter of which has garnered increased attention for its New England IPA-influenced brands. Over the course of the three-day event, the plurality of beers served are IPA or a Pale Ale masquerading as one, hopped to high heavens and occasionally murky as a milkshake. Drinkers couldn’t get enough.

One after another, festival denizens made it clear: the beer they think about most is IPA.

“Every other beer I make is an IPA or an APA,” a Reykjavik homebrewer says in passing. “It’s good because at a party, you can drink IPA all night long.”

Taken in its collective context, the interests of locals starts to sound of the same sentiment heard in the U.S. not long ago. Drinkers are looking for something unique and different, manifesting itself in a rebellion of beer palate. If Lager was Iceland’s start post-prohibition, IPA becomes a logical endpoint, offering a way to easily distinguish flavor and experience. A generation ago, U.S. craft brewers stuck their middle finger up toward an adjunct establishment. Now it’s evidently Iceland’s turn.

“The New England-style IPA, that’s what everyone wants,” says KEX brewer Steinn Stefánsson. “Doesn’t matter if you’re from the States or Iceland or Fairview Islands. If you know a little about beer, that’s what your craving is.”

By the estimate of Borg Brugghús’ Long, there are only six or seven year-round IPAs made in Iceland, and he’s responsible for two of them, including the first recognized, mass-release Icelandic IPA in 2011.

For Borg, Ulfur (“Wolf” IPA) and Ulfrun (“The Wolf” session IPA) comprise about 40% of his brewery’s production, bumped up a few percentage points further by the seasonal release of Ulfur Ulfur (“Wolf Wolf” double IPA). The ingredients used across all three sound straight outta the West Coast, featuring hops like Citra and Mosaic (session IPA), Amarillo and Simcoe (IPA), and Centennial and Amarillo (DIPA).

“General interest has been changing a lot in the last few years,” Long says. “Two years ago, maybe, the majority of people didn’t relate to hearing the name 'IPA.’ Now, an average beer drinker knows what an IPA is and I think it’s going to be a very normal thing a year from now. People are demanding more IPAs from us and they can’t get enough.”

U.S. influence in Reykjavik is hard to miss, from three popular hot dog stands scattered across several blocks in the city’s center to the nearby Chuck Norris Grill—not to mention other restaurants plainly called American Style and American Bar. A storefront proudly advertises “Texas Pizza Pie,” whatever that is. At a downtown flea market, one booth is full of U.S. military-style clothing.

There are plenty of ways from which to view the weight of American culture (especially in beer), but Icelandic brewers are still trying to find ways to highlight their own country through small batch one-offs using foraged fruit like bilberries and crowberries—tarter, tougher versions of a blueberry. After last year’s Icelandic Beer Festival, Ellertsson and Stefánsson made an “Icelandic version” of Surly’s beloved Imperial Stout, Darkness, with Surly head brewer Jerrod Johnson, using birch syrup, locally produced chocolate, and roasted coffee. Recently, the pair collaborated with Sweden’s Brewski brewery to make a sour ale inspired by skyr and blueberries, an Icelandic dessert found everywhere, from rural dining room tables to upscale restaurants.

“We get inspired by a lot of breweries, but not Icelandic breweries.”

Other interpretations of what makes a beer “local” sound more exotic. “Since we don’t have any forests, the traditional Icelandic way of smoking meat is with sheep manure,” explains Borg’s Long. (Here’s hoping the Germans are more focused on America than Iceland if shit is a part of beer making process in the latter now.)

“We made our own smoked malt with this method for a German-style Rauchbier and now most foreigners that Google us find stories about this malt,” Long continues. "It wasn’t supposed to be a big thing, but when we go to festivals abroad, everyone wants a taste of it.”

But a curious thing has happened on this path of creativity: it got paved over by the steamrolling power of the hop. The youth of Iceland’s beer scene, coming of age now as IPA can be found all over the world, coupled with the ease of which its brewers can travel abroad and learn from others, has pointed them in the same direction. With so many breweries starting in recent years, both in America and elsewhere, the relationships forged among newcomers means that trends and ideas carry among their cliques. Even across oceans.

“We get inspired by a lot of breweries, but not Icelandic breweries,” Stefánsson says.

Kai Leszcowitz’ first trip abroad to represent Aslin Beer Company was for this year’s Icelandic Beer Festival. He got a personal invite from the KEX crew when they visited his not-yet-two-year-old brewery in Herndon, Virginia last year. How did Scandinavian brewers wind up at a small American brewery that doesn’t sell outside its own taproom due to demand? Simple: Aslin, like the other American breweries in Reykjavik for the event, is known for its IPA. But especially its hazy, hop-bombed, New England-style versions.

“What most of American craft breweries are known for are these interesting, hop-forward beers,” Leszcowitz says. “The fact that Iceland is adopting that as their first go-to beer is a positive sign.”

In Iceland of all places, the words “Tree House” and “Trillium” are consistently dropped by beer lovers, which also explains why breweries like Other Half and Boneyard appear alongside established international hop artists like Pirate Life. All these breweries are connected by their relative youth, finding inspiration amongst each other like members of the same high school class. They’re growing up together in the ultimate foreign exchange program, sending ideas and experiences back and forth, more often than not surrounding the lupulin-laced trend that brought them together in the first place. The siren song of Columbus, Cascade, and Citra is heard all over, translated into every language.

A trio of Russian tourists stand next to me at the bar of Bryggjan Brugghús, a brewpub nestled in a trendy area of Reykjavik’s downtown harbor. Along with an array of in-house brands, a small cooler behind the bar holds cans of Stone Go-To IPA and assorted hoppy products from BrewDog.

Ordering two Bryggjan IPAs and an unusually cloudy Pilsner, the outlier of the three, in her best English, succinctly explains why she didn’t choose a hop-focused beer like her friends: “I do not like the bitter,” she says.

The chalkboard at the bar makes it clear it would like visitors to like otherwise, showing a Pale Ale made with Columbus, Citra, and Mosaic hops, and an IPA boiled with Columbus and Amarillo, then dry-hopped with Citra, Mosaic, and Centennial. This does not feel out of place from what I might find in my home of North Carolina. A waitress says the Pale Ale is their most popular choice.

Both beers, unabashedly American in their creation, taste like something from the East Coast in the early 2000s. The Pale Ale is piney as hell, bitter all the way through, a stark contrast to how the style is often now made Stateside, using a lower ABV base as a mode of transport for “juicy” hops. Bryggjan’s IPA is similar, but with more vague citrus flavors hiding throughout. Both would have made for solid additions to a Dogfish Head portfolio 15 years ago.

Put in context of where Icelandic beer is heading, they fit right in. This book has been written before, authored by American brewers. Large scale Lager factories will probably never go away, but change can start with extreme tastes that will eventually make way to more nuance. An exercise to find new and opposing drinking experiences is clearly underway.

Ellertsson says that in 2010, 98% of beer sales in Iceland’s liquor stores were Lager, and that that number was down to 78% in 2016. Fact or not, it’s part of this tale that would be easy enough to believe. It’s hasn’t even been 30 years since full-strength beer was produced on the island, but six years is a lifetime of trends in beer. IPA is sold in the airport duty-free shop.

“Icelanders are fast at picking up things,” he says.

Does that lead to assimilation or merely experimentation? It could go either way when it comes to beer. The degree of which one is chosen over another can easily get lost in a sphere of influence that expands rapidly. When trend-watching, it’s important to keep an eye on what’s in the middle pushing outward, as much as what comes from new changes along its edges.

In countries all over, even Iceland, a thirst for new beer experiences is increasingly satiated by the aromas and tastes cultivated thousands of miles away in America. Influence can come from anywhere, but a 72-hour peek into what makes beer a culture in Reykjavik presently feels oddly right at home.