In America, there is nothing worse than an Irish pub. In Ireland, there’s nothing better.

The Irish-branded bar in America is likely to be the opposite of local—a fixture of airports and tourist-trap sections of town, known more for its interchangeability than its unique character. It’s probably carpeted. At the very least, a faint beer-sour smell lingers in the air, punctuated by the occasional waft from the deep fryer in back. Look up, and the walls are covered with beer-logo mirrors of dubious vintage and provenance. Guinness logos abound. You’ll find a few standard beers on tap and a modest happy hour. Unless, of course, it’s St. Paddy’s Day—in which case all-day drink specials are the norm.

In other words, I never took much interest in these fixtures of the American urban landscape. Which isn’t to say I never drank in them. At one of my first jobs, the after-work watering hole of choice was a pub on the ground floor of an office building across the street. After shutting down my computer for the day, I’d obligingly head over with my fellow coworkers (well, the ones in their 20s and a few of the older men, at least), where we’d have a few rounds of Bass Ale paired with rubbery mozzarella sticks or chicken fingers.

My other American Irish-pub experiences have scarcely been better. I’ve been dragged into them because a friend’s boyfriend’s out-of-town friend has insisted we meet there. I’ve stopped there for a single whiskey because I’m early to meet someone for dinner next door. I’ve ended up there with groups of friends too large to find seats at a more desirable bar nearby. Such bars are seemingly engineered to turn otherwise innocuous social experiences into reminders that our lives are bland and unremarkable. But really, it doesn’t matter that these places are kind of depressing because, unlike a good pub in Ireland, the American Irish bar isn’t a place you seek out or try to make your own. It’s just somewhere you end up.

But perhaps that’s an unfair distinction. I’ve never actually sought out authentic Irish pubs, either. Probably because I was unimpressed by the mediocrity of the American version, at no point did I go out of my way for a warm-wood Irish pub where I could sip bitter, creamy pints served with a side of banter instead of the mozzarella sticks. I ended up in real Irish pubs through seemingly no active choice of my own. The difference is, once I found my way there, I wanted to keep going back. When you fall in love with an Irishman, you accept the pub into your life and heart.

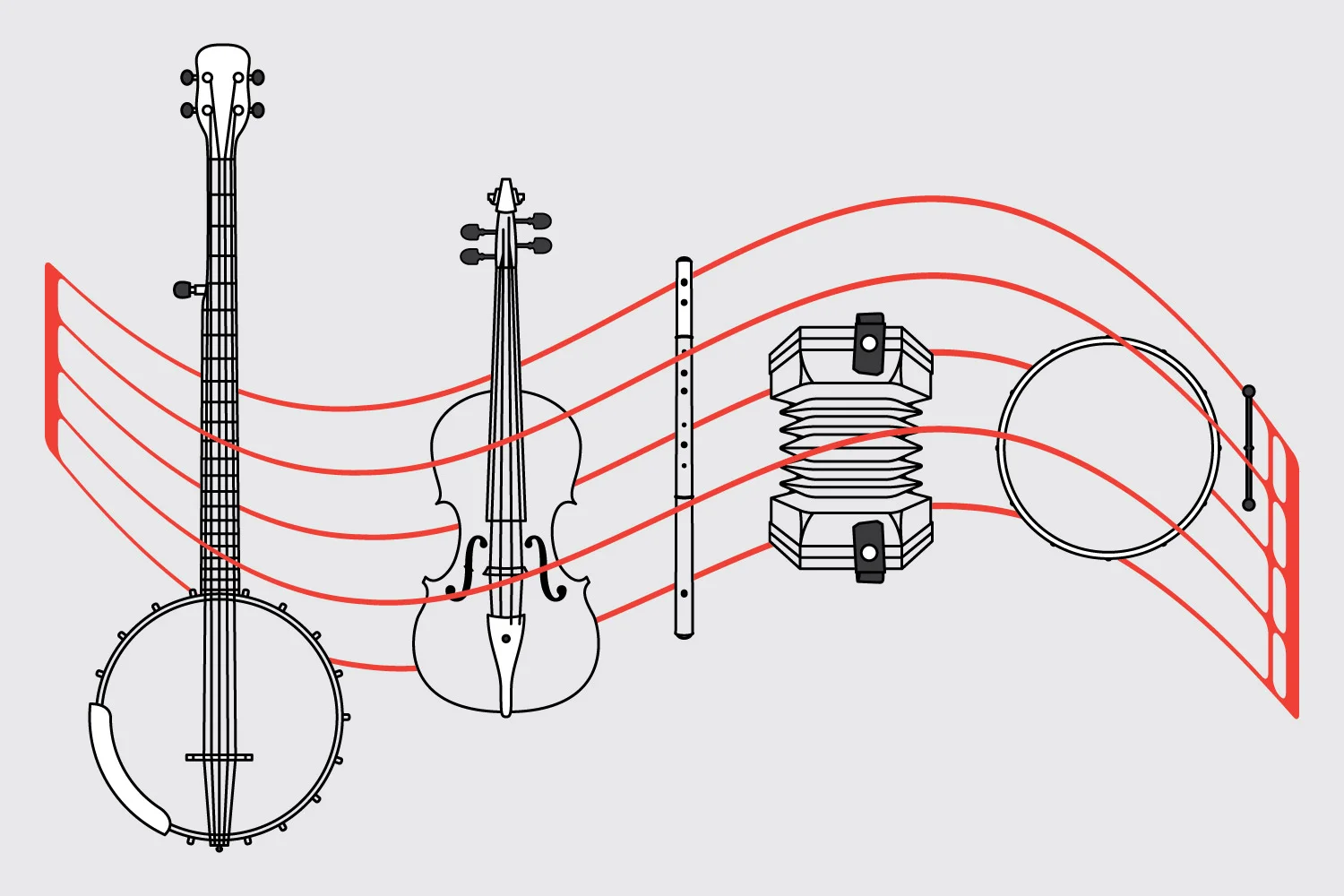

He lived in London at the time, but he took me to Ireland just a few months after we met. Before the trip, his father asked if he was taking me to the pub to see some “fiddle dee dee,” or Irish trad music. He added, “Yanks love it.” In retrospect, it’s easy to see that a tour of rural Irish pubs was a requirement of the heady early days of our relationship, the time period when you are eager to introduce your new love to everything that’s important to you. I’m fairly certain that our now-solid relationship would have been a mere fling if he’d put a fresh pint of Guinness in front of me and I’d wrinkled my nose. Not to worry, though: this Yank loved it.

Anyone with a passport can probably guess that the American version of the Irish pub doesn’t have much to do with the drinking establishments it’s bastardized. But I quickly realized that, despite a few superficial similarities, they are in fact almost opposites. The American Irish bar caters to those who enjoy darts leagues and trivia nights and TVs blaring sports. Around closing time, it’s a truly depressing place to be. At decent Irish local, you’ll find the inverse: people of all ages at most times of the day and evening, engaged in conversation, with perhaps a little live music to entertain them. It embarrasses me to admit how appealing I find this, given that white Americans in search of their roots have thoroughly romanticized this scene already.

As the daughter of Iowa teetotalers who has never set foot inside a bar with more than one family member in tow, I did not fully anticipate how much this multigenerational clientele would move me. But it did! The Irish pub, I realized, never stood much of a chance in America, where “family bar” is an oxymoron.

The Puritan view of booze as antithetical to the wholesomeness of residential life—rather than an essential element of it—won out over the traditions that Irish immigrants must have carried with them. Maybe, if I were to search back far enough in my Midwest bloodline, I’d find a few German-Irish ancestors for whom the pub was central to their sense of community. But in my lifetime, the bars have mostly been clustered in business districts or pushed out to strip malls by the highway.

It was something I didn’t really even question until I saw both teenagers and grannies sipping their half-pints in the local pub. (Yes, I have seen grannies in the pub. And yes, you can order pints in half-sizes, which is a nice way to keep things moderate.) I was sold. And that was before I even had my first sip of Guinness.

Which doesn’t mean it’s all friendly craic and fiddle-dee-dee. My personal pub tour guide is from Northern Ireland, born to a Protestant father and a Catholic mother. On both sides of the border, we stick to pubs that are family-approved for reasons of aesthetic preference as well as local politics. When I press for more information on how one can tell whether a bar is friendly to people of all religions and accents, I don’t get much of an answer.

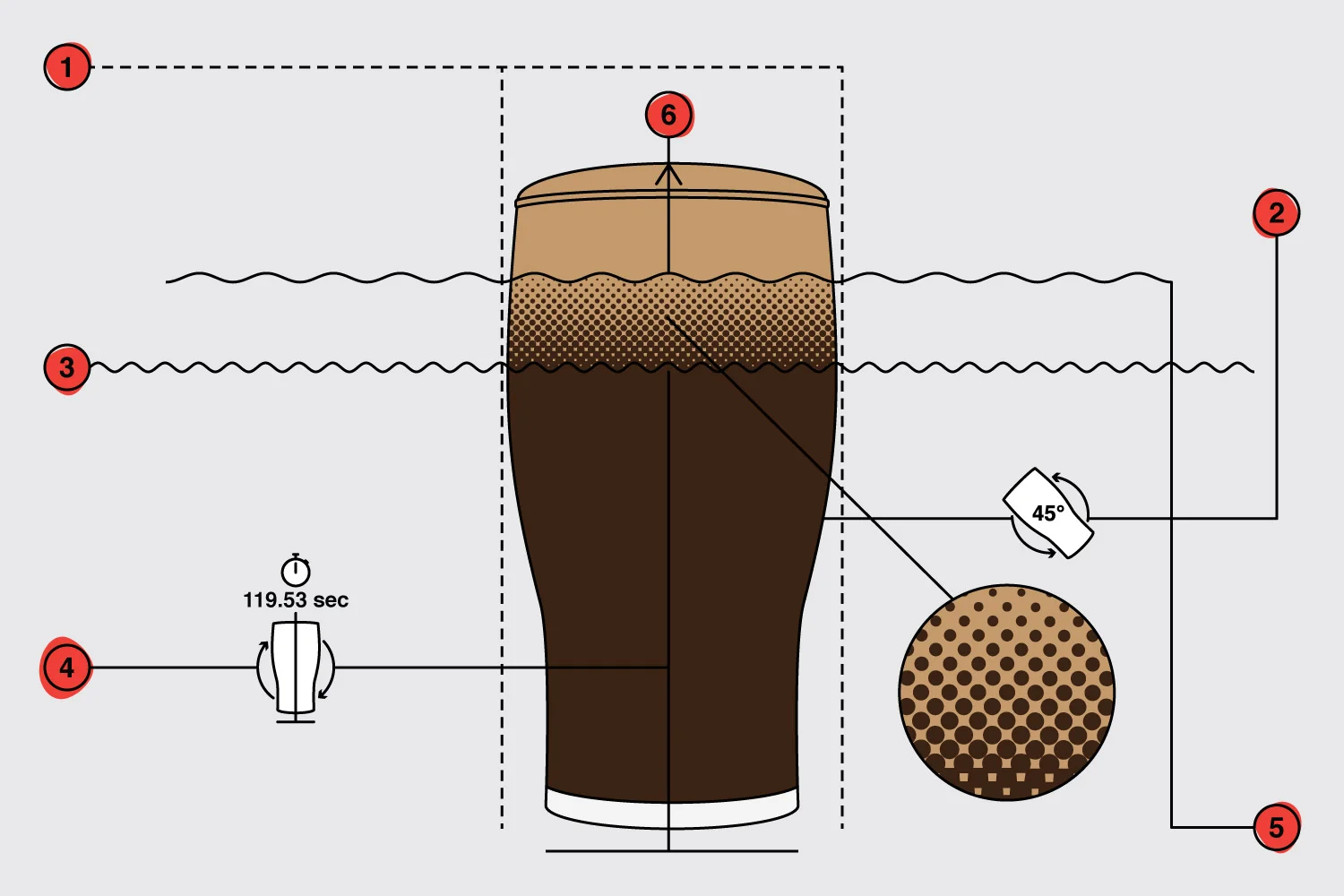

He does tell me—and I immediately agree—that what Americans have heard is true: Guinness, poured in the approved six-step method, is better in Ireland. That this is because people drink more of it in Ireland, which means the taps are clear and not gunked up with old beer. He—or any tourist who has done the Guinness brewery tour in Dublin—will also probably tell you that any good barman or barmaid in Ireland knows how to pour a proper pint using the method, which goes like so:

*Angle the glass at 45 degrees

* Pour until it reaches the bottom of the harp logo on the glass

* Turn the glass upright, letting it settle for 119.53 seconds

* Fill to the top of the harp logo

Whatever they’re doing, it’s working. Better-tasting Guinness in Ireland is confirmed by some independent research. Last year, scientists at the Institute of Food Technologists took non-expert taste-testers to 71 bars in 33 cities in 14 countries, and asked them to rank Guinness on a scale of 1 to 100. The pints from Ireland scored about 20 points higher than pints poured elsewhere.

Then again, I’m also comfortable with the notion that it tastes better because the pubs in Ireland are better. Because you’re drinking it while the bartender talks your ear off and gives you a hard time about your American accent and tells you a bit of gossip that is fairly meaningless to you, but feels important somehow and is certainly entertaining nonetheless. Because the clouds are so moody outside and this weather is perfect for drinking a Stout. Because most drinking is done in rounds here, which means you’ve had a bit more than you planned on because someone else is always buying. Because your Irishman is pleased to show off this hidden gem of a rural bar, a place where his family has been stopping for a pint for many, many years.

And, because each pint is a mere 4.1% ABV (gloriously low if you’re used to drinking American craft Stouts, for instance), you can have a few at that country pub in the afternoon, clamber into the passenger side of the car, and gaze up at those moody clouds while you’re whisked away down the winding country road, taking hairpin turns slightly too fast and braking for sheep, and not even feel the slightest bit nauseated. Just content. Ready to check out another, different pub after dinner.