At first glance, it’s hard to understand what Chris Baerwaldt is doing in the Czech Republic.

Around 6,000 Americans currently live in this South-Carolina-size country in Central Europe, and the vast majority of us live in the capital, Prague, or another city. Many of us are here because we don’t want to drive all the time—Prague has one of the world’s best public transportation systems, and cross-country trains are both frequent and cheap. Or because we want to geek out on the incredible Baroque and Gothic architecture, most of which is in cities like Prague and Český Krumlov. Most of us would probably say we enjoy the country’s laid-back, Central European-lifestyle. And at least a few of us are here because we fell in love with Bohemian Pale Lagers and we can’t stop drinking them.

Baerwaldt doesn’t really tick any of those boxes. Instead of living in a city like Prague, he and his wife, Soňa, settled in the tiny Bohemian village of Zhůř (2011 population: 54), about 20 minutes south of the great brewing town of Plzeň, aka Pilsen. Their house is newly built, and it doesn’t look all that different from a suburban home that they might have lived in back in California. They both drive regularly, and Chris still works for the same company he worked for in the States, telecommuting from a home office. On the surface, their lifestyle looks pretty damn American.

When it comes to drinking beer, Baerwaldt fits in a bit better. The Czechs are known for drinking the world’s largest amount of beer per capita, as well as for several beer-related firsts, like the first Pilsner and the original Budweiser. The average Czech consumption is around 144 liters per person, or about 302 U.S. pints per year, compared to the American average of about 160 pints.

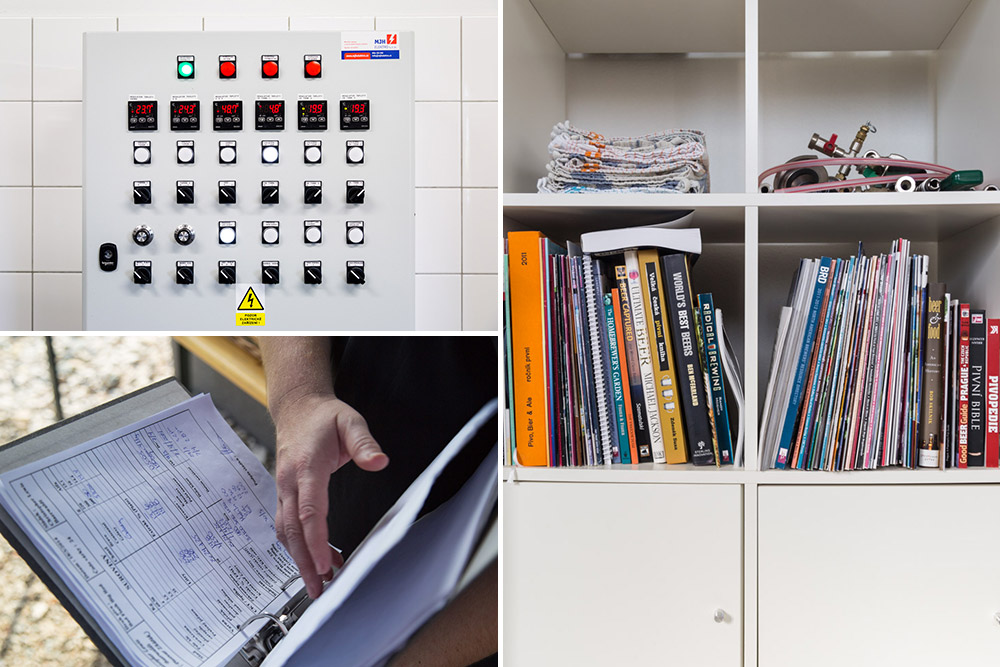

I’d guess that Baerwaldt himself probably clears 600 pints without breaking a sweat, something he was probably doing before he left California, since he used to be the IT guy, Guy Friday, and occasional brewer at Hoppy Brewing Company in Sacramento. In fact, he loves beer so much that he even opened his own brewery in Zhůř, Pivovar Zhůřák, constructing a separate building with its own driveway, address, and electricity meter behind his house, not to mention jumping through all of the other arcane hoops of the Czech health, legal, and tax codes. The fact that Baerwaldt has his own brewery means that he and Soňa have a constant supply of beer to drink, and in this way, he’s like the most Czech dude ever.

Except that he’s not. Because while the Czech Republic is the country that created Pilsner, and Baerwaldt himself lives less than 20 miles from the place where the classic beer was invented, Pivovar Zhůřák started out by focusing exclusively on American craft styles, like IPAs, Imperial Stouts, and other top-fermented brews.

Despite the American approach, the name itself—which translates, roughly, to something like Brewery Zhůř-guy—is almost ridiculously Czech, containing not only the language's almost-impossible-to-pronounce “ř,” but also the bizarrely long “á,” to say nothing of the ooh-sounding “ů.” (Oh, and the “z” and the “h” in “Zhůřák” are pronounced separately. Good luck with that.)

So Baerwaldt moved to the country that drinks the most beer per capita, almost all of which is some kind of Pale Lager, many of which are absolute world classics like those from Kout na Šumavě, which is only 35 miles from Zhůř. The entire Czech Republic currently produces some 20 million hectoliters of beer annually, punching so far above its weight that it produces the world’s 15th largest amount of beer, even though it’s only 87th in terms of population.

“It’s like a vast ocean of great Lagers, both pale and dark. And in the middle of it, Baerwaldt is making his own American-style ales on a tiny, 250-liter (2.13-barrel) system in a Bohemian village that just might be the exact geographic center of fucking nowhere.”

It’s like a vast ocean of great Lagers, both pale and dark. And in the middle of it, Baerwaldt is making his own American-style ales on a tiny, 250-liter (2.13-barrel) system in a Bohemian village that just might be the exact geographic center of fucking nowhere.

What in the world? And why?

Baerwaldt didn’t move here to brew, of course, but he had been a homebrewer long before he and Soňa settled in her homeland in 2008, and he continued once they got here. Pretty quickly those homebrews started to catch the attention of beer fans in the Czech capital. I first met the pair at a homebrewing competition in Prague in late 2008, and when Baerwaldt entered the next Prague homebrewing competition in 2010, he won both the ale category and the overall prize.

“That was really amazing, because I didn’t expect to get anything,” he says. “I just wanted to be part of the Czech beer community, and it’s always fun to hang out with other homebrewers.”

The win was actually kind of a big deal, and it made Baerwaldt start to consider going pro. He sought advice from people like Martin Matuška, Jan Šuráň, Honza Kočka, and other Czech beer luminaries. Eventually he hired the great brewmaster and brewing advisor Josef Krýsl to build a brewery in his backyard.

“I was just glad that someone with an ale background—I mean not only drinking ales, but also brewing them—would try to establish a brewery here,” says Kočka, a brewer, writer, and organizer of numerous beer events in the Czech lands, including the Prague homebrewing competition. “It’s like talking to native speaker of English instead of a foreigner who is learning English. Big difference.”

Another big difference: the time it would take to set up a professional brewery, as well as the expense, when compared to the cheap and nearly immediate gratification of homebrewing. To pay for it, Baerwaldt convinced his wife to let him raid his 401(k). Setting it all up actually took a few years. It wasn’t until mid-2013 that Pivovar Zhůřák was officially open for business.

Well, at least sort of. Brewing 250 liters at a time makes for a pretty small footprint, at least on paper. In all of 2015, Pivovar Zhůřák brewed a total of just 108 hectoliters, or about 92 barrels. The brewery is profitable, but it’s hard to call it a business. “Zhůřák is kinda just for me, in a way,” Baerwaldt says. “I like brewing beer. I’ve homebrewed for over 25 years now. And I like sharing beer with other people. Zhůřák lets me get it out to other people and share the beer I like to drink.”

This is where you can start to make an argument that, much like the Czech Republic, Pivovar Zhůřák is punching above its weight. Today, much of the Old World is losing its ever-loving mind over American-style craft beers, the Czech Republic included. As it turns out, when you drink the world’s largest amounts of beer, there’s plenty of room for an IPA or Imperial Stout every now and then, even if you think it tastes kind of weird compared to your traditional světlý ležák (pale lager) or tmavé pivo (dark beer).

Unfortunately, Europeans don’t always have unfettered access to U.S. craft beers, a situation which can create some strange—even comical—results. There’s an apocryphal story about the first generation of craft brewers in Italy intentionally brewing cheesy, stale-tasting IPAs, because the only American IPAs they’d ever tasted were six months past their prime by the time they reached Rome or Milan.

Zhůřák is like the exact opposite of a European brewer trying to recreate an American style he’d only ever read about, or only tasted in a superannuated, over-oxidized state. Baerwaldt is putting out the kind of beers he knows from back home, both as a homebrewer and at Hoppy Brewing. So although he’s only brewing a minuscule amount, those beers have been carefully sampled by other brewers, beer bloggers, pub owners, and beer fans. In a way, he’s provided a baseline for an entire South-Carolina-size country to understand what a West Coast IPA or a Hoppy Amber Ale should taste like.

Jiří “Bejček” Stehlíček is the owner of the celebrated Prague beer bar První Pivní Tramway, one of the first pubs to offer Zhůřák beers. I ask him if he remembered what his customers thought when they first tasted those beers. “For them, and for me, they were like a vision,” Stehlíček says. “He was brewing completely different beers than anyone else at the time. Everyone here always looked forward to the next brew from Zhůřák.”

You can see how Zhůřák beers are viewed on the Czech beer blog, Pivnici—most of them have earned “excellent” or “outstanding” ratings. (Full disclosure: I might have helped brew one or two of those beers. Also, when Baerwaldt won first place in the ale category of that Prague homebrewing contest in 2010, I came in second. But I digress…)

You can even argue that Zhůřák’s influence extends beyond the beer itself. When Baerwaldt started brewing here in 2008, Czech craft beer names usually carried the stodgy monikers of the country’s traditional beers: Pivovar Václav, for example, might put out Václav IPA to complement its Václav světlý ležák. But Baerwaldt has a screwball-slash-juvenile sense of humor, and his beers carry goofy names like Man Boob Enhancer and Red Shorts. I’m not saying that new Czech craft brewers like Pivo Falkon—with its Falk:On and Falk:Off Imperial Stouts—copied Zhůřák’s naming style, but Baerwaldt is definitely a pioneer in his own weird way.

And that weirdness is helping to change the local culture. In fact, you might say it’s already changed. Today, Falkon, Raven, Lucky Bastard, and an entire generation of Czech brewers are putting out brews in solid American craft styles. None of those brands existed when Baerwaldt moved here in 2008.

“The thing with him is that he started off with Hoppy Brewing recipes, so he had a clear idea of what he wanted the beer to taste like, while a lot of Czech breweries didn’t have a really clear idea of what they were doing,” says Filip Miller, one of the owners of Pivovar Raven and a longtime admin for the Czech pages at RateBeer. “At festivals, you’d see the other brewers trying Zhůřák. Originally, they were probably just asking, ‘What’s this American guy brewing?’ Maybe even with a bit of skepticism, because that’s the reputation of American beer here. Then, they would be very surprised, because the Zhůřák beers would be really different—really bitter, really aromatic—than anything they’d ever tasted.”

“I’m always looking forward to meeting friends at Slunce ve Skle and asking if they’ve had Zhůřák yet,” says Jiří Stehlíček, referring to one of the country’s premier beer festivals. “And if not, I drag them straight to Chris’s stand and watch their eyes widen.”

So maybe that’s what Chris Baerwaldt is doing here: making eyes widen. Providing a baseline for what a decent Pale Ale or American Wheat is supposed to taste like. Changing the local beer culture.

(There’s another difference, too, another way that Chris and Soňa are changing the culture, albeit at a more personal level. When the last Czech census was taken in 2011, their tiny, west Bohemian village of Zhůř had just 54 residents and, of course, no brewery. Most obviously the Baerwaldts have given their village a brewery. On a more personal level, they also added three more young citizens to the local population.)

But culture is a two-way street, and the Czech Republic has plenty of it to give. It took a while—more than three years, in fact. But just this summer, Chris Baerwaldt finally released Pivovar Zhůřák’s first Pale Lager.