At its peak in 1890, the city of Cincinnati produced more than 1.13 million barrels of beer. That same year, each Cincinnatian consumed, on average, 40 gallons of beer—two and a half times the national average. It was dubbed the “Beer Capital of the World.”

Alas, the heyday was short-lived.

A majority of the city’s breweries and biergartens were owned and operated by German-Americans in the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood. Anti-German sentiment surrounding the first World War drove people toward spirits and to other parts of town. The breweries that managed to survive until 1920 were promptly shuttered by Prohibition. Few ever reopened, and the city’s brewing tradition never fully recovered.

But in the last few years, a host of new brewers have tried to revive that bygone heritage and wake the sleeping giant of Cincinnati’s brewing industry—and its beer-drinking community alike.

Nearly everything about Urban Artifact is unexpected. Their location in an old church and gymnasium in the Northside neighborhood. Their brewing and fermentation methods. The acoustically-perfect music venue in their taproom. Even the very beginnings of the brewery. Spontaneity reigns throughout.

“I was frantically trying to get a hold of Bret because he was out in the middle of nowhere, hiking the Appalachian Trail,” Scotty Hunter says, a bit of a fever pitch still in his voice as he recalls those days in 2014. “When I finally reached him, I said, ‘You’ve got to come home. Right now.’”

“We were in Hanover, and we had to make a decision immediately,” Bret Baker explains. “The next day we bought bus and plane tickets and were on our way home. Two weeks later, we signed a giant SBA-backed business loan, and here we are.”

At the time, Baker and his wife were 45 days into a planned six-month trek. In Baker’s absence, Hunter was approached by Dominic Marino and Scott Hand—UA’s other two owners—about a partnership, after a previous agreement had fallen through. Marino and Hand were more interested in the music venue side of things, and needed a brewing partner that shared their vision and values.

Baker and Hunter were on board. They’d been working on a business plan together since graduating from Ohio University. Both chemical engineering majors, the brewing bug hit them hard at OU, where they started the university’s first homebrew club. Though they didn’t brew any wild or sour beers in school, that’s when they developed their love for those styles.

“When people hear the word ‘sour’ they think it’s going to be super-tart like a Warhead. But there’s a level of sour for everybody.”

“The first sour I remember having was a Lindemans Framboise,” Baker recalls. “It was sweet. Really sweet. But it was eye-opening. And it started us down this rabbit hole of unknowns and excitement in beer.”

Urban Artifact was at the other end of that rabbit hole, opening in April of 2015. Even without the music venue, the brewery is unique to Cincinnati.

“We do spontaneous fermentations with local, wild-caught yeast and bacteria,” Baker says. “We do Brettanomyces-only and mixed-culture fermentations. And we do a lot of modified sour mashes using a house Lacto strain. Nothing like this is going on even remotely close to us.”

After a normal mash, Hunter runs off into a dedicated souring vessel. There he can control all the parameters—temperature, oxygen exposure, pitch rate—and monitor the standard gravity, pH, and total acidity. Once the wort reaches the desired measurements, it gets pumped back into the boil kettle and finished like normal.

The result is a more approachable, more controllable flavor profile. “It keeps the beer clean,” Hunter says. “We can really dial in the level of acidity in each of our core beers.”

What really makes their beers unique, though, is the character of their wild-caught yeast and bacteria. “The beauty of catching wild yeast is that it’s all about locality,” Baker says, waxing poetic about the process. “To me, there’s really no other way—aside from water, maybe—to get a true terroir in beer. But wild yeast does. And there’s beauty in that. It’s just such a romantic idea.”

So far, the guys have isolated and used eight wild-caught strains, each with a different profile. Those strains, combined with the house Lactobacillus and modified sour mash, help to create what Hunter and Baker call “the spectrum of sour.” It’s a term they use to describe their lineup of beers, but also their approach to educating drinkers.

“When people hear the word ‘sour’ they think it’s going to be super-tart like a Warhead,” Baker says. ”And some sour beers are like that. But there’s a level of sour for everybody.” To prove that, Urban Artifact’s beers span the pH scale.

Maize, their Kentucky Common, has but a hint of tartness—it’s almost imperceptible if you’re not expecting it. Their Goses—Harrow and Chariot—pack quite the punch. The latter even more so, due to the addition of cherries. Outside the realm of sour, UA’s Brett-only beers have a comparatively soft, rounded, funky quality. And with beers like Phrenology and Hippodrome, their Single and Double Wild IPA, the guys come close to something that could be considered mainstream.

“Some people come in thinking they want our IPA,” Hunter explains. “But that’s the perfect lead-in for us to get their attention, because we don’t have a standard IPA.”

“It gives us the chance to start a dialogue,” Baker says, finishing the thought.

“‘Do you like bitter flavors or hoppy flavors? Have you ever had a sour beer? Do you want to try something different?’ And then we slide them something tart.”

Both guys explain the typical process of a customer taking their first sip, their face contorting before coming to rest, chancing a second sip, and raising their eyebrows in a what-in-the-world-did-I-just-have sort of way. That’s when the conversation really starts.

“At the end of the day, it’s all about education,” Baker says. “Communicating with our customers and building a common vocabulary. Having that wide range of sour flavors gives us a lot of talking points and helps people really get into it.”

Those new sour fans will be key to Urban Artifact’s growth. Currently, they’re draft-only, with about a hundred accounts in the Cincinnati area and a handful more in nearby Dayton. Limited-release bottles and an expanded barrel-aging program are on the horizon, but they still rely heavily on traffic in the taproom. It’s there that they pair their offbeat beers with offbeat musical acts.

“Getting extra exposure through the shows is almost like a marketing tool for us,” Hunter explains. “Because we have so many different shows and such diverse crowds, we expose so many people to our beer who might otherwise never try it.”

Trying your first Gose while watching an all-female Rage Against the Machine cover band is an example of what makes Urban Artifact such an important addition to Cincinnati’s brewing landscape. Their commitment to live, local music—and live, local bacteria—is a true differentiator, while their focus on education is becoming standard practice across the rejuvenated market. And that education through their spectrum of sour will be absolutely integral as the Cincy market continues to grow, and their unexpected beers are tried by more and more people.

U.S. Route 50 starts on the east coast (Ocean City, MD) and ends on the west (Sacramento, CA), passing directly through Cincinnati in the process. The road is Manifest Destiny manifested, and embodies its ideals of exploration and growth and expansion. And now it serves as an appropriate namesake for Fifty West Brewing Company as they prepare for an expansion of their own.

Located on Route 50, about 10 miles northeast of Cincinnati proper, Fifty West occupies one of the oldest buildings in the area. Built in 1827, it was a residence throughout the Civil War until after the turn of the century. It served as an overnight rest stop for Abraham Lincoln, became a speakeasy during Prohibition, transitioned into a full-fledged brothel, was partially burnt down in the ‘60s, housed various restaurants after that, then sat vacant for a number of years until 2008. That’s when Bobby Slattery’s family purchased it.

“We didn’t really know what we were going to do with it,” Slattery admits.

Blake Horsburgh used to drive by the building every day. “I saw a sign that said, ‘If you have any good idea for this space, give us a call.’ So I did,” he remembers.

Since that call, and Fifty West’s opening in 2012, Horsburgh, Slattery, and the brewery have been growing together. But they’ve reached that tricky tipping point between capacity and demand, and have decided to expand the taproom into a full production facility. As part of the expansion, they’ll move primary brewing operations across the street, to the other side of Route 50. There, they’ll more than double their current output of almost 2,000 barrels annually to more than 5,000—with a capacity of 25,000 barrels in the future. It wasn’t an easy decision, though.

“I saw a sign that said, ‘If you have any good idea for this space, give us a call.’ So I did.”

“We lucked out and hit this craft beer wave right in the middle,” Horsburgh says. “That’s been very advantageous for us, but it’s also been our biggest struggle. Do we expand just because we’re supposed to?”

“Even a year ago, the easy next step would’ve been for us to just make as much beer as possible,” Slattery continues. “But how does that make us different? How does that create an experience for our customers? So we decided to stay true to ourselves and keep doing what we were doing and build a community.”

The term “community” gets tossed around a lot in the beer industry, almost to the point of losing any real meaning. Things are different at Fifty West. To them, the idea of community isn’t really about the beer at all—it’s about everything you surround yourself with before, during, and after having a beer. It’s about the things people drink to naturally when they get together, whatever that might be.

To that end, adjacent to the new production facility will be a bevy of non-beer things to do: a collection of sand volleyball pits, a cyclery situated at the foot of the bike trail, and a canoe livery on the Little Miami River.

“More than the product itself, it’s about the experience,” Slattery says, his eyes lighting up. “If we can get people who are really enthusiastic about cycling to come in here after a ride and learn about beer, that’s a win. Or vice versa. That’s the extra element that’s going to add value to someone’s life.”

Consumer education is important, too. “We’ve found that if you talk with them a little bit, if you ask them the right questions, you can help them discover which flavors they’re drawn to,” Slattery says.

While they’ve got a wide range of beer available—12-15 distinct styles on most days—to help folks hone in on exactly what’s right. Conversations usually start around their gateway beer, Speed Bump, a lightly hopped Kolsch with a bit of yeast presence. It gives them the platform to talk about things like hoppy versus bitter, the sweeter and roastier sides of malt, and the role yeast plays in developing flavor. The goal of Speed Bump isn’t to get people drinking more Speed Bump, though Slattery and Horsbugh certainly wouldn’t mind that. Rather, it’s to “move [the consumer] down the road” to other, more complex styles. Each person and each path is different.

And for all the time they spend educating their customers, lately, the guys have been trying to learn as much as possible from them in return. With expansion on the horizon, Horsburgh and Slattery are trying to figure out which beers outside their core lineup should get scaled up with those new buildings across the street. And, eventually, which beers get packaged for retail. Keeping their ear to the ground helps guide the choices they make moving forward, and helps them balance what they’re personally passionate about with what there’s a market for—a balance that’s increasingly more of a challenge to reach as the Cincinnati beer scene gets more crowded.

“We’re still trying to figure out what we want to be when we grow up,” Horsburgh jokes. “But Fifty West and Cincinnati are growing together, arm in arm, and it’s really cool to be a part of.”

When Bryant Goulding tells the story of Rhinegeist he sounds kind of like a CEO presenting a thinkfluencing TED Talk on the origins of his thriving Silicon Valley startup. He uses phrases like “demographic analysis” and “open-source” and “Enneagram personality test.” He’s not being cold or callous, though, and there’s still a lot of romanticism there. It’s just that the full picture doesn’t become clear until he talks about culture. Culture’s the bridge between Goulding’s background as a consultant at Accenture and his time as a west coast rep for Anderson Valley and Dogfish Head. It’s the lens through which he looks at everything, including growth. And it’s the thing he wants most for Rhinegeist and the city of Cincinnati.

“Bob called me on my birthday and said, ‘Come to Cincinnati. We have to build a brewery. There’s all this history here, but there’s no Cincy beer on tap,’” Goulding says. Bob is Bob Bonder, Goulding’s business partner and the guy who ran the numbers to know a brewery like Rhinegeist was viable in The Queen City. “He had done an analysis on what cities have the demographics and population but aren’t saturated with small coffee brands. He had it narrowed down to Raleigh-Durham and Cincinnati.”

After he got to Cincinnati, though, Bonder realized that a brewery could be just as, if not more, viable than a coffee roaster. Instead of catching commuters on their way into the city in the morning, he’d catch them on their way home in the evening. Goulding picked up and moved from San Francisco to Cincinnati. “I got here and I was sleeping on Bob’s couch, and we worked to revise the business plan,” he remembers.

Plan finalized, the first order of business was to find a location. And what better way to instill culture in a new brewery than to set up shop in an old one. Rhinegeist found its home in the former Christian Moerlein bottling plant in the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood—a relic dating back to 1895 and the city’s days as the “Beer Capital of the World.”

The building was chock-full of personality, and growth potential, with more than 25,000 square feet of usable space. With an aggressive growth model built into the business plan, that extra space was a necessity. But it ended up getting used even sooner than expected.

“We wanted to do 1,600 barrels in year one, 3,000-6,000 in the first three years, [and] get to 25,000 in seven years,” Goulding laughs. “Cincinnati was way thirstier.”

Rhinegeist ended up producing around 30,000 barrels in 2015 before they even hit their third anniversary.

A vast majority of that growth was on the back of a single beer: an India Pale Ale called Truth. But it was almost a beer they couldn’t even make their first year in business. Truth’s hook lies in the tropical aroma and dry grapefruit finish, both achieved through a hop-blast method of massive Amarillo late additions. The problem was, nobody had heard of Rhinegeist in 2013, so no growers would contract the amount of Amarillo they needed.

“We were naming it Truth,” Goulding says, exasperation in his voice. “IPAs aren’t a style you can really mess around with. You’ve got to come strong and we had no idea what do to. We just started calling all our friends and asking if they had any Amarillo. Then I remembered Jamie Floyd from Ninkasi saying that he was the biggest user of Amarillo hops in the country. I called Jamie and they had enough to spare. We swapped them out 700 pounds, and that was that.”

“The culture we hoped to build, we built by Bob and I interviewing every single person we hired.”

Truth was an instant hit in the market. But even before the orders started rolling in, the guys knew they were onto something big. Opening day of their taproom saw 2,500 people roll through, with a minimal amount of marketing effort. Goulding ended up calling in reinforcements: his brother was pouring beers with his uncle, his dad was checking IDs at the door, his mom was bussing tables.

“We were absolutely floored,” he says. “We knew we had to staff up quickly.” Rhinegeist now has more than 100 employees, each one handpicked by Bonder or Goulding.

“The culture we hoped to build, we built by Bob and I interviewing every single person we hired,” Goulding says. “It was a huge time commitment, but it was the best investment we could’ve made.”

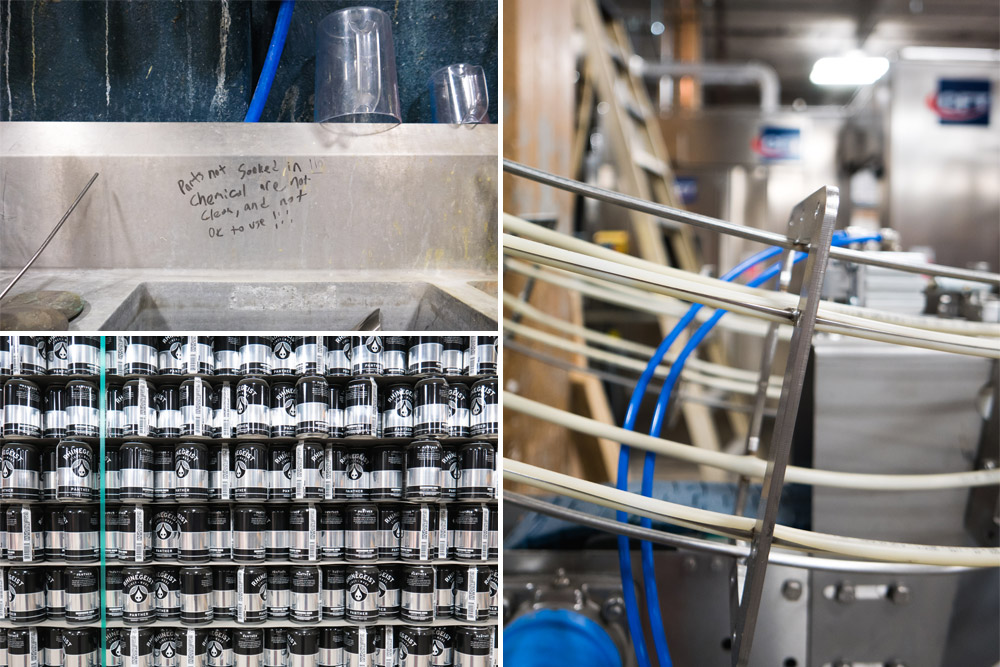

One of the ways Rhinegeist shows how much their beer, and their people, matter, is through a commitment to education. Every single employee—from the head brewer, to the bartenders, to the guys on the canning line, to folks dropping off the kegs—knows what hops are in every beer. Not only that, but the brewery now offers Cicerone classes for anyone interested. It’s an investment in the employees, but it’s also an opportunity to bridge the information gap as a self-distributor. As good as a wholesaler can be, they can be juggling a hundred other brands. If your delivery driver can speak to the bartender or shop owner about the beer he’s dropping off, the more likely that knowledge will make its way to the customer. And in the end, Goulding knows that educating the customer is what makes a strong beer culture within a city.

“We’re keenly aware of the culture and history here in Cincinnati,” he says. “But we’re also aware that it hasn’t been fully reconnected to the new craft movement. That’s exactly what we’re trying to do.”

The brewers in Cincinnati know they’re on the edge of something big. They talk about how there are murmurs of “it” coming back. “It” being the good old days when Cincinnati was making—and drinking—more beer than anywhere else in the country. It might happen, too, but breweries like Urban Artifact, Fifty West, and Rhinegeist aren’t resting on their laurels waiting for it. Even with all the growth that’s happened over the last five years, there are only 18 breweries within the city as of the BA's 2014 published numbers, and they produce just north of 100,000-barrels* annually —a far cry from the city’s high point of more than a million.

(*Although the Brewers Association includes the ~800,000 barrels produced by Boston Beer Company at its Cincinnati facility in their city and state production totals, we’ve omitted them from the totals reflected here. Instead, the totals of the breweries whose identity, reputation, and primary market is tied to the city have been included.)

There’s ground to make up when it comes to market maturity and acuity in order to be on par with Cleveland and Columbus, yet alone other places in the region. But if there’s a city with the history and heritage to make it happen, it’s Cincy.

“Cincinnati is one of Ohio’s historic cradles of beer with modern-day craft brewers concocting their unique beers in the bones of bygone breweries,” says Mary MacDonald, Executive Director of the Ohio Craft Brewers Association. “It’s exciting to see the current wave of Cincinnati craft brewers making their mark locally and regionally—and hopefully regaining the city’s reputation as a formidable force in our national craft beer culture.”

This is the final installment of a three-part series chronicling the state of craft beer in the Buckeye State, and how it could lend insight into national trends and future growth for the industry.