Philadelphia is part of the sprawling urbanity along the Eastern seaboard of the US, from Boston, southeast to D.C, with New York, Baltimore, and Philly in between. It’s also constantly fighting against the encroachment of an unruly deciduous jungle so thick that bus lanes in the burbs have to cut rectangular-shaped holes through three-lined roads just to make passage possible.

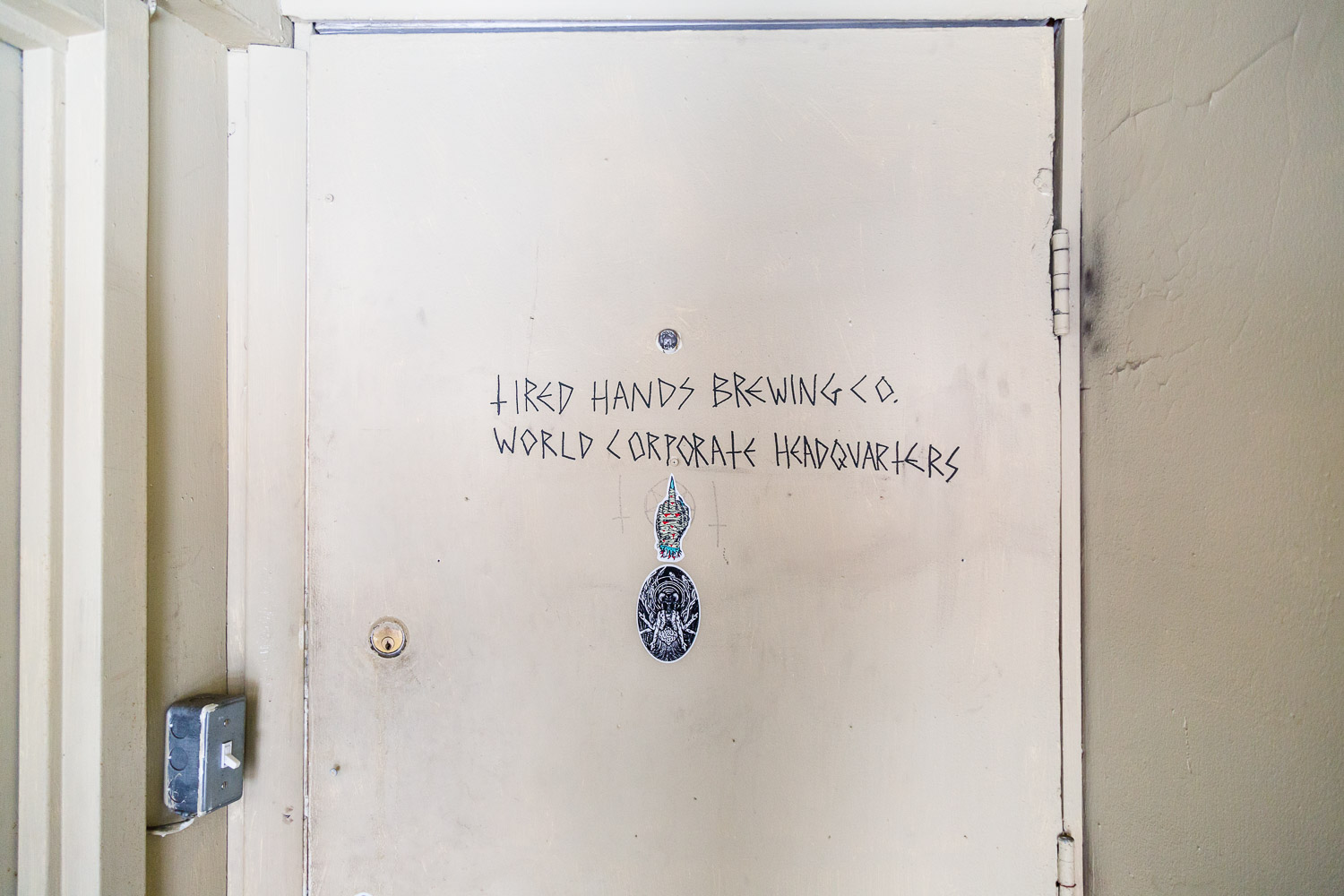

Depending on the angle of your approach to Tired Hands Brewing, you’ll pass through communities like Wynnebrook, Manayunk, Bala Cynwyd, or Bryn Mawr — names that sing of their Native American roots as much as their Welsh, Irish, English, Dutch, and so on. Tired Hands Brewery is nestled into the town of Ardmore near the Philadelphia Main Line train running along Lancaster avenue, which connected the country estates of the region’s wealthiest families to the city. All that old money is still there, and quite explicit. But so is a fresh new vision for food and beer from some artistic counter-culture types.

"Yeah, we freaked them out,” founder Jean Broillet IV laughs. "And that’s our stated intent: weird and serious, strange and beautiful."

Jean Broillet IV (I didn’t ask him about the roman numerals) sees Tired Hands as a bit of a singular business, even beyond it’s third-wave brewing status.

"There’s a lot of Irish pubs in Ardmore," he says. "There’s a lot of people here that have money that are very used to things the way they are and 'should be.' So none of that was really taken into consideration when we built, but I think that from a quantifiable standpoint, we generate a lot of tax revenue for the town — especially for events and special releases. And if they didn’t like us or understand us, hopefully they like us from that standpoint."

Like many new small businesses in the Philadelphia area, Tired Hands had to squeeze their concept into the nooks and crannies of an existing building — some parts dating back to near-colonial times. Buildings like this force their history onto a new business in a purely geometric sense. You want to fit a tank in there? You better find some short little grundies and wedge it into a spot under some low-hung ceiling, or under the stairs, or maybe in the basement that used to be a doctor's office going back a hundred years. That’s that kind of tetris-like skills, and patience, it takes to open a small brewery in a neighborhood like Ardmore.

Despite their physical constraints at the original cafe brewery, Jean and his growing team are making beers reminiscent of the wide-open spaces of the farmhouse brewer. Rustic, yeast-driven ales, often hop-forward, sometimes barrel aged (the few they can wedge under the basement rafters), and increasingly fruit-fermented. But for the first phase of their development, the constraint was as much about time as it was space.

“We generate a lot of tax revenue for the town—especially for events and special releases. And if they didn’t like us or understand us, hopefully they like us from that standpoint.”

“Throughout the first year we were putting out some borderline raw IPAs. I mean, some of our IPAs would sell out in a day. And that's six to seven barrels just drained in a day. You can go down to our serving room, or into our cold box and watch the sightglass on a Thursday or Friday night just drop precipitously, which is insane and scary."

For a homebrewer going pro, a small 7-barrel system might seem like a rational leap to make. You can get familiar with production-level procedures, cleaning regiments, and turn batches quickly to experiment with what you and your customers want to drink. But Jean already had that kind of experience brewing for locals like Iron Hill, seven or eight years worth. For Tired Hands, starting small was once again just a matter of physical constraint.

“When we were conceptualizing the café, this was it. This pure, little, regional delight that people travel to Ardmore for, and they almost have to find it to enjoy it. But outside of my best attempt to create a building that was long-term sustainable, we started beating the shit out of it because we were so busy right out of the gate."

Jean was the “general contractor” on the build-out, which took eleven months. And while he was happy with the results, he never expected it to be wall-to-wall every night with customers and brewing seven days a week to keep up. "I guess the term would be 'riding it hard, putting it away wet.'” says Jean. "And it’s so true in a amphibious environment like a brewery, and just in terms of ease-of-use and labor hours, labor dollars. At the time, when we made the decision to expand, it was two guys, myself and another brewer, brewing seven days a week. And it was usually a brew and a transfer. We reached the point where, I don’t want to say rushing beers, but we were pushing beers along."

That tension between brewing to a superior level of quality and artistry, and wanting to meet demand he never anticipated, pushed not the just production of Tired Hand’s beer, but Jean’s tolerance for scale and complexity. “If I could do it better I wanted to. So that’s when we began looking for more space. It’s a stated intent in my business plan to keep eight beers on tap at all times, so I set that bar and wanted to maintain that bar, at least for my own sanity and, I guess, pride."

Jean didn’t underestimate foot traffic, or the slice of the market that craft would take in his region. He’s a smart enough guy to make strong, conservative estimates on the business side. What surprised him is how much of a cultural chord his brewery, and his beers, were going to strike — even far beyond the Philadelphia region. The internet has fundamentally changed craft brewing, maybe especially for those brewers on the smallest of scales like Tired Hands. If word gets out about a special product, or a special brewery, the country knows about it overnight. And the next morning, locals are lining up to get their hands on the beer, and a large percentage of their buy is getting shipped to curious drinkers all over the map. But that kind of demand is impossible to plan for, and even harder to keep up with.

"We put growler restrictions in place within the first year,” explains Jean. "I never would deny the psychology of rarity, and perhaps that’s what we’re talking about here — factors that went into us needing more room pretty quickly."

That’s when the Fermentaria came in to view. A short walk away, Jean and his team built a second location. For all the constraints of the cafe brewery, the Fermentaria is a zenith of possibility — an enormous block of squared-off, high-ceilinged, open-windowed construction where they’ve lined up tanks and stacks of barrels that will serve their growth for some time to come. It also has hundreds of seats for the large kitchen serving food with a locally-sourced mind-set. And as excited as Jean is about their new digs, he’s also cautious about the unguided momentum that so many breweries find themselves trying to gain control of after an expansion.

“So what Saison Dupont can’t do is emulate our house profile, which is growing and evolving every day and which is sort of a singularity amongst a lot of these more modern American yeast-driven brews.”

"I never had any delusions of taking over the world with my beer, and I still don’t want to do that. The reason for growth within Tired Hands, within this company, is purely sustainability. I don’t want that cafe building to collapse on a busy Saturday night. [laughs] I don’t want the quality of our beer to drop, and the big-picture thinking is that we’re part of an amazing beer scene here, especially in Philadelphia. One of the best in the nation, if not the best."

Philadelphia is a brewing town with a highly discerning eye, and cares about quality above local across the board. With fresh-as-can-be imports coming in from Europe, the city has developed a certain palate for complexity and nuance that can be underdeveloped in newer markets in the US that are still obsessed with hop-bombs, and where “local" is still the biggest flavor. It’s also been producing local craft far longer than most US cities, so while the trend of balanced, sessionable beers is ramping up from the West Coast, Philadelphia has been here for years. That makes for an exciting customer base, but it also makes for a highly competitive retail market with an even higher bar for quality.

"I was really awakened by the Chicago beer scene when I first visited a few years back,” Jean recalls. "We walked out of bars there and it was like, holy shit, man! I can get three Half Acre beers. They have five Three Floyds beers on here. That was something that I wasn’t used to seeing because Philadelphia took a little more of a scattershot approach where local was represented, but so was everything else."

The beers that Tired Hands is producing sets their competitive targets beyond just local producers. They’re not just coming at buyers with a new IPA story. They’re looking to win over lovers of European saisons, Belgian beers, and the like. “Our focus was to just brew beers that we wanted to drink — over-archingly dry and expressive beers, pungent beers, which have roots all over the world — and just brew them here. So, if you’re a beer buyer in Philadelphia, you can get it here now,” Jean explains.

Most saisons produced in the US are actually using a commercialized DuPont yeast to emulate the iconic saison that so many American brewers fell in love with. Jean claims he’ll never produce a beer as beloved and fundamental as Saison DuPont. And that’s fine because that’s not exactly the point. "What Saison Dupont can’t do — and I say this with humility — is emulate our house yeast profile, which is originally intended to be an homage to Saison Dupont. We take very good care of our yeast and that's a very broad, honest statement. We’ve only purchased one pitch of our yeast from the lab. We banked it. We isolated it. We propped it. We homebrewed with it when I was brewing at Iron Hill — this is what my wife and I were doing. We blended it, and then we sent it off to the lab, and now it’s in the cryo-freezer. So what Saison Dupont can’t do is emulate our house profile, which is growing and evolving every day and which is sort of a singularity amongst a lot of these more modern American yeast-driven brews."

That’s not to say they aren’t as IPA-obsessed as the rest of the country. But when they set their sites on a style, they tend to explore further than most. “At the Fermentaria right now we have, I think, like six IPAs on, which is cool. It’s a mediation on the style and kind of taking the style to its outermost limits."

Realizing that Philadelphia hadn’t yet shown an abundance of local support from retailers (and likely never will, at least not by default) helped the team create a sales approach that looked at the long-term vision rather than spreading themselves too thin. “We’re cultivating relationships and we’re going deep,” explains Jean. "Like Local 44 up the road — I think they have three Tired Hands beers on right now. There’s a spot, Als of Hampton [aka Pizza Boy] in the Harrisburg area that might have ten of our beers on right now. And that’s like a meditative analysis. You can go in there, and they have our imperial porter on, they have our pale ale, and I think they have Shambolic, which is a dry-hop saison—three wildly different styles that are all of very high quality from the same producer. That’s badass, and that’s culture for us."

Tired Hand’s sales lead, Bobby Clark, came from Weyerbacher — a large local producer started in 1995 with a capacity of over 30,000 barrels and a 40-barrel brewing system. Jean describes Bobby as a "hands-on, DIY, punk-rock-kind-of-dude" who likes the trials and tribulations of loading up kegs, making the calls, doing the e-mails, writing the invoices. "He’s 360, and we love him for that,” says Jean. When you ask Bobby what he wants from the new hustle, he never breaks eye-contact with the computer screen. He just tosses over his shoulder in a calm, that’s-a-dumb-question kind of voice: “I want to take over the world.”