“There is no patron saint of bottling,” says Father Mateusz, the Trappist monk responsible for brewing at Mount Saint Bernard Abbey in Leicestershire, England, as he tries to fix the labeler on the bottling line which has been mis-aligning for over an hour. Peter Grady, the secular brewery manager, laughs. “Maybe we should pick a saint and pray to them, and if it works this could be their first miracle,” he suggests.

Fr Mateusz has been awake since 3:15 a.m., as usual, and was in the church by 3:30 for the first of the day’s seven liturgical prayers. He then prayed privately in his room until soon before 7 a.m., when he arrived at the brewery. His work begins early to ensure he’s finished in time for the evening’s penultimate prayer at 5:30 p.m. As a Trappist monk, his life is structured around the schedule of daily prayer, with a morning and afternoon period of work. In addition to brewing, Fr Mateusz is also the monastery’s beekeeper and bookbinder.

There are 157 Trappist monasteries—officially known as the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance—around the world, of which 87 house monks and 70 house Trappistine nuns, with a global population of around 1,400 monks and 1,350 nuns. They all work to support their monasteries in some capacity, whether by cooking, doing laundry, and looking after elderly members of their community or by manually producing goods to sell. There are Trappists who make cheese, chocolate, honey, and greetings cards; others are bakers, potters, farmers, candlemakers, and carpenters. And, as of late 2022, there are 10 Trappist monasteries where authentic Trappist beer is brewed.

The names of those beers—Westmalle, Westvleteren, Orval, Rochefort—carry a special lore. But while I’ve known that they are all made within the context of a monastery, I don’t have any knowledge of what it means to be a monk, of what that life is truly like. It’s something that I want to experience for myself.

Mount Saint Bernard Abbey is now home to the newest Trappist brewery. It sold its first beer on April 23, 2018, which is also the day of St. George, England’s patron saint. It is England’s only Trappist brewery, and it brews just one beer: Tynt Meadow, a Strong Dark Ale named after the field where the monastery was founded in 1835. That field, and the many acres of farmland surrounding it, is where the monks used to make their living as dairy farmers. By the early 2000s, milk production was no longer financially viable, so they made the difficult decision to leave behind a practice they’d always known to undertake something they knew nothing about.

Now beer is the monks’ main source of income, and the brewing of it has to find balance within the rhythm of Trappist life.

Fr Mateusz doesn’t brew in his monk’s habit, and most of the time I see him, he’s wearing utility cargo pants rolled up at the bottom and a frayed worker’s smock with bleach marks and sewn-on patches. He usually wears Crocs, but when bottling he swaps them for steel-toed boots before donning a colorful headscarf.

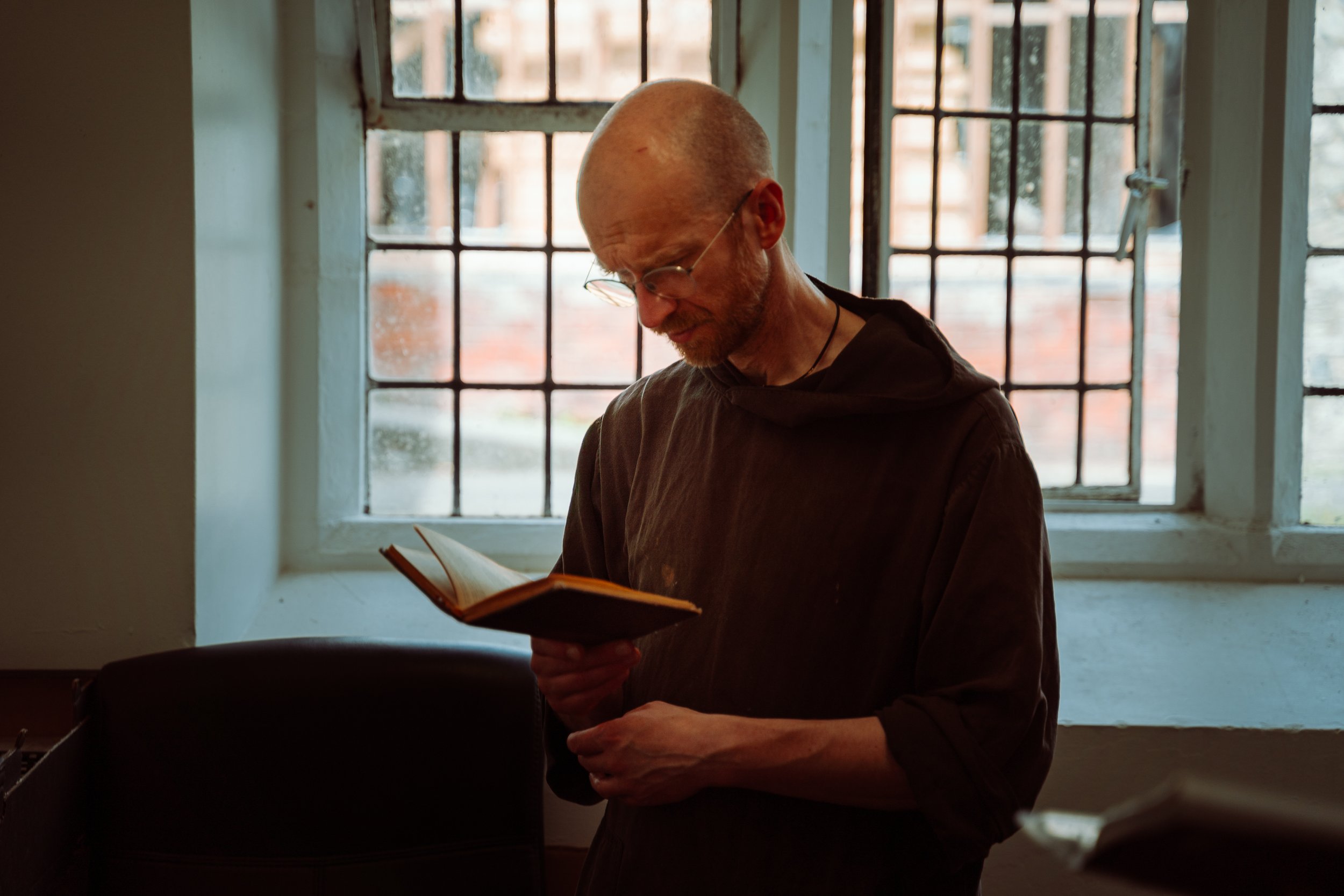

Now in his early 40s, Fr Mateusz has been a monk for 21 years, initially in his native Poland and at Mount Saint Bernard Abbey since 2018. A calming and thoughtful presence, he takes a beat before answering questions, and is quick to smile when recalling stories from books, movies, religious texts, his personal experiences. One day he brings me a copy of Wisława Szymborska’s “How to Start Writing (and When to Stop): Advice for Writers”; another day he bakes an extra loaf of sourdough bread for me to eat in the guesthouse, and we drink his homemade lemonade while we talk in the brewery. It takes me a couple of days to sense that his calmness comes with something deeper, a profound contentment and happiness which I come to recognize as joy.

Fr Mateusz didn’t arrive at Mount Saint Bernard Abbey with the expectation of becoming a brewer. He’d never made beer before, and had been a beekeeper in Poland; plus, there wasn’t a brewery at the monastery yet, though it had been commissioned. He found his new vocation as he settled into the community, doing whatever jobs were required of him, which is how he learned to bind books. Fr Mateusz had been at the monastery for a year when he was asked if he’d like to take over the brewing from Fr Michael, the monastery’s first brewing monk, who had decided to move to Mount Melleray Abbey in Ireland (the mother house of Mount Saint Bernard Abbey).

“Monastic life is very rhythmic, it likes repetition. When you have just one beer, you have to keep everything the same. It’s very monastic. Just keep doing it all the same, all the time. At the beginning, everything [in the brewery] was terrifying, every next move I was completely focused on brewing, but when you repeat the same over and over again, you can master it. The more you master something, the more free you feel.”

“It was so attractive I didn’t have to think too much. I just wanted to help the Abbot,” says Fr Mateusz. He worked with Fr Michael, read books in his private time, made as many notes as he could, and traveled to Abbey Maria Toevlucht in the Netherlands (which brews the Zundert Trappist beers under supervision from technical brewing advisor Constant Keinemans, who was also responsible for setting up the Mount Saint Bernard brewery).

“First, I learned blind. I do not understand what I am doing, but I am doing it,” says Fr Mateusz. “I had to learn how to make a beer without understanding the process.” But the more he brewed Tynt Meadow, and followed the processes he had learned, the more he gained knowledge of what he was doing, and why.

“Monastic life is very rhythmic, it likes repetition. When you have just one beer, you have to keep everything the same,” he says. “It’s very monastic. Just keep doing it all the same, all the time. At the beginning, everything [in the brewery] was terrifying, every next move I was completely focused on brewing, but when you repeat the same over and over again, you can master it. The more you master something, the more free you feel.”

It’s been 10 years since the monks at Mount Saint Bernard Abbey stopped working their 180-year-old dairy farm, and walking around the grounds, you can still see the remnants of that old enterprise: the barns, the sheds, the rusting equipment, and the many acres of land which surround the abbey, now rented out to a local farmer to graze sheep.

The decision to close the dairy and say goodbye to the cows was such a difficult one that it was put off for many years. “Some old monks were so attached to the cows, they’d be heartbroken,” says Brother Martin. “They were really against [closing the dairy], even though everybody could see it wasn’t viable anymore. We had to [pay] into it to keep the farm going.” When German-born Br Martin arrived at the monastery in 1994, there were 40 monks and 80 cows, and farming had always been done on a modest scale, sufficient and manageable for the monks. But large-scale dairy farming had since cut the price of milk, and the work was becoming more challenging for the aging community of monks. No matter that the monastery had succeeded until then because of the farm—it couldn’t continue any longer. But it wasn’t clear what should come next.

Some monks wanted to keep the cows and make ice cream from the milk, but in the end the monastery decided to pursue brewing, inspired by the famous Belgian Trappist breweries. The project was led by then-Abbot, Dom Erik; a documentary, “Outside the City,” was filmed during this time, capturing the process from conception to the beer’s release. It depicts much of the development, and some of the challenges, of the process, and it offers a revealing look inside the cloister.

The community took their time with the brewery. It was important that the beer and brand represented them properly, that the brewery could fit within their monastic life. And the works have fundamentally altered the monastery. What used to be the refectory is now the bottle store. The kitchen is now the bottling room; the laundry became the brewhouse; the kitchen storeroom is now the warm room for secondary fermentation. Beyond just building a new income source, the brewery posed a change to the monks’ daily lives. Even something as simple as eating lunch in a different room is significant for someone who’s eaten in that same place, every day, for decades.

“Obviously to build one Trappist brewery, it’s [an honor]. When they ask you to build a second, it’s unbelievable. And in a country where there is no Trappist brewery. It’s very special.”

Outsourcing much of the planning to Constant Keinemans provided some relief and reassurance. In addition to his work at Zundert, he is also on the technical commission for the International Trappist Association, meaning he works with all 10 Trappist monasteries. He visits them periodically to ensure that they still meet the criteria of a Trappist monastery: namely, that the beers have been brewed within the immediate surroundings of the abbey, that production is carried out or supervised by monks, and that profits are used for the needs of the monastic community or the development of charitable projects.

“I had a phone call from [the brewing monk at] Westvleteren,” says Keinemans. “He said to me, ‘I have some monks from England and maybe they want to start a brewery.’” Keinemans spoke with the monks at Mount Saint Bernard, and several went to visit him to see the brewing of the Zundert beers. Later, they asked him to manage their own brewery installation.

“Obviously to build one Trappist brewery, it’s [an honor],” he says. “When they ask you to build a second, it’s unbelievable. And in a country where there is no Trappist brewery. It’s very special.” Managing that transition at Mount Saint Bernard Abbey involved much more than just building a brewhouse, he says, because the monks knew nothing about beer or brewing.

In his initial trial batches, brewed on a 30-liter Grainfather kit, Fr Michael made beer modeled on a Belgian Tripel. “I spoke a lot with them. I said to them, ‘Why do you want to brew a Belgian-style Tripel?’” says Keinemans. Instead, he guided them towards a beer that was recognizably Trappist while still being rooted in British brewing and ingredients. “It must be your beer,” he told them.

Numerous test batches followed, all of which were tasted and commented upon by the community, until Tynt Meadow emerged as a 7.4% ABV Strong Dark Ale brewed with all-British ingredients, though it has echoes of a Trappist Dubbel. Now the monks continue to be present at regular tasting panels, giving feedback on each batch.

The monastic community was also influential in designing the beer’s branding. The logo reflects the lancet windows of the church; the Tynt Meadow font comes from a 12th-century Cistercian script, updated by one of the brothers who was an artist; the simple white label cutaway presents their countryside location.

“You can say that this is really our beer,” says Fr Mateusz.

The church bells wake me every morning. I’m staying in the monastery guesthouse for the week, in a small room similar to those where the monks live, with a single bed, desk and chair. There’s a communal kitchen and dining room, and shared toilets and showers. I’m here to follow the monastic life, attend church prayers, and spend my working hours in the brewery.

Every morning the bells ring at 3:15 a.m., and then again 10 minutes later. The monks’ first prayer of the day, which begins at 3:30 a.m., is known as Vigils. It begins with psalms, then progresses into a quiet contemplation. It’s a nocturnal solidarity of monks keeping watch while people sleep, both in anticipation of Jesus Christ’s return, and to pray for people who are in a spiritual, figurative, and literal darkness.

When the bells chime again at 4:15 a.m.—they toll with the rhythm of prayer and work, calling to action rather than announcing the time—I know the monks are leaving the church to return to their rooms for their private prayers.

At 6:55 a.m., the bells ring to call the monks together for Lauds, which celebrates the daybreak. The church is now open for the public to attend, and will remain so until after the final prayer of the day, which finishes by 8 p.m. Lauds becomes my favorite time of day during my stay in the monastery.

In the morning, the church smells like warm milky tea and musky wood. Architecturally austere—a deliberate choice, so as not to be distractingly ornamental—the church is still beautiful as the rising sun shines through the lancet windows, illuminating the monks. They stand in the chancel in their habits—a white tunic and black scapular fastened with a leather belt—and in the mornings wear a white hooded cowl over the top.

I sit in the nave and listen as one monk plays an organ, keeping a slow pace as the choir calmly chants the psalms, their voices volleying softly back and forth, the cadence imperceptibly increasing, the tone gently lifting us into the day.

After Community Mass and Holy Communion, the morning work period begins, scheduled from 9:30 a.m. until 12 p.m. There are 17 monks in the monastery, and each takes on different roles (three monks are in their 90s, and continue to work where they can). Some jobs are more manual, dealing with creation and restoration. Br Martin is a potter and works in the monastery gift shop; Br Andrew is a carpenter; and Br David makes candles and looks after some chickens. (The difference between Brother and Father is that some monks choose to become a priest, and when ordained by a Bishop they take the title Father.)

Others work on the daily runnings of the monastery. There is a launderer, an archivist, an infirmarian, a guest master, and a bursar. There are also secular, or “lay” people, employed around the monastery to do work which the monks cannot do for themselves. Peter is the brewery and operations manager, Neil is the gardener, Adrian is the buildings manager, Mary is the cook, Maria works in the shop, and Sue is the accountant.

Three short prayers mark mid-morning (Terce), midday (Sext), and mid-afternoon (None). While monks should be in church if they can, sometimes they will be working and unable to attend these prayers, known as the Little Hours, so they will say the psalms and prayers alone in their own time—this is what Fr Mateusz does when he’s brewing or bottling.

Lunch is at 12:30 p.m. Most Trappist monks follow a simple vegetarian diet, but at Mount Saint Bernard they also eat fish several times weekly. Breakfast and evening meals can be taken when the monks choose, featuring foods like cereal, bread, and cheese, but at lunch they eat communally, in silence, while someone reads (“spiritual food and physical food,” is how Br Martin describes it to me). Some Trappist monasteries—including some which don’t have a brewery—serve a beer everyday with lunch, but at Mount Saint Bernard Abbey they choose to offer each monk one bottle on a Sunday. (Sunday follows the same structure of prayers but there are no working hours; it’s considered their day of rest.)

Afternoon work begins again at 2:30 p.m. and lasts for two hours, with the monks continuing whatever tasks they have for the day. Two prayers end the day: Vespers at 5:30 p.m., and finally Compline at 7:30 p.m., which is a calm and gentle service, the church now smelling like chamomile, lavender, incense, and burned-down candles. Everything is slower at this time of day—the organ, the chanting, the prayers—the service like a lullaby. When the bells ring one final time around 7:50 p.m., the day is done and the monks retire to their rooms for bed, ready to repeat the same again tomorrow.

There’s rhythm to brewing as there is to the monastic life. On their 16.7-barrel system, they brew a double batch on alternate weeks, usually brewing on Friday and Saturday to fill a 33.5-BBL fermenter. On weeks when they don’t brew, they package that volume over the course of two days. The monks decided on an output of 838 BBLs per year (or some 300,000 11.2oz bottles), and they are happy to maintain that volume.

The brewery is doing well. They will soon bottle batch number 100. Tynt Meadow is sold out a year in advance, and it sells around the world, where it’s particularly popular in the Netherlands and Scandinavia. But this isn’t a commercial enterprise—it’s technically a charity—and even though they could sell more, the priorities here are different. Any decisions to brew more or less, or to add new beers, must consider the community first.

The most common question Peter has to answer is if there’ll be another beer. “The answer is yes, probably, but it could be one year or it could be five years,” he says. Any changes in the brewery could impact the monastic way of life. The brewery is within the monastery buildings, and the rattle and rumble of forklifts, delivery trucks, and the bottling line shouldn’t be disruptive to the preferred quiet.

This week the schedule has shifted slightly, so bottling will take place today and the following day (on Tuesday and Wednesday), and brewing will be on Friday and Saturday. I’m spending my working time in the brewery, doing whatever jobs I can: packaging, cleaning, moving pallets of beer, emptying sacks of malt into the mill.

Today, Fr Mateusz’s first job is to add a mix of priming sugar and yeast into the packaging tank for the beer’s bottle conditioning. That had gone as planned, but by the time I arrive at 8:20 a.m., the labeler is causing problems. For over an hour, bottles go onto the line, through the labeler, then are removed, their labels pulled off, and the empty bottles run through again. “It’s not normally like this,” says Fr Mateusz, maintaining his calm despite the situation. Bottles slowly proceed through the line, but we stop more often than we move, until gradually, without noticing it happening, we’re moving with a steady flow of bottles coming through.

I’m working at the end of the bottling line. I take a flat-packed box, put two corners between my hands, push hard, and it pops open. I take four bottles, put them in the box. Take four more, put them in the box. Four more and the box is full. Close the lid, seal it, put the box on a pallet. Take another box. It’s repetitive work, broken up by quick chats, by full pallets needing to be moved, by bottle caps falling to the floor which need picking up, by choosing to fill the box in different patterns, by having to speed up or being able to slow down.

Soon after the 12:30 bells ring, we break for lunch, which we eat together in the small brewery office. Fr Mateusz, Peter, and Br David say their prayers together before we all return to the line, with the bottles now moving at a consistent speed, filling without issue, metronomic in their motions, allowing the mind to drift and daydream, until the 4:30 p.m. bells tell us that the working day is done. We start at 8 a.m. the next day, and I quickly step back into that flow of opening a box, grabbing bottles, filling the box, closing it, placing it on the pallet. By lunchtime we’ve filled nine pallets with bottles of Tynt Meadow.

After helping with cleaning down, I have the afternoon spare, so I go to see Br Martin in the brewery shop. “When you stand at the gates of heaven, you can say that you spent £26 in that monastery one day,” he says to a man who’d come in to buy two bottles of beer and was leaving with much more in his arms. If you visit the monastery, it’s Br Martin that you’re most likely to see; he’s a friendly and chatty man, speaking with a soft German accent.

As well as working in the shop, Br Martin runs the monastery’s pottery studio, and he’s a photographer, taking photos for calendars and books—all of his items are sold in the shop. He also looks after five chickens, which live in a pen nicknamed “Jurassic Park” (there’s a photo book of the chickens for sale, though tragically the titular “Magnificent 6” have since been reduced by one). We go in search of the chickens, which have free run of the old farm buildings and green spaces next to the brewery, and when they aren’t in Jurassic Park we look in the orchard. He claps his hands and all five run towards him through the long grass. One jumps straight up into his arms.

Mount Saint Bernard is a monastery, but it’s also a place with its own quirks and characters, just like any community. Br Martin offers to show me the local nature reserve on Thursday morning, and when we meet he’s wearing Nike sneakers and running shorts. “Shall we run?” he asks, before shooting off at a pace I struggle to keep up with. One evening I see Fr Terence chasing Br Leo through the guesthouse, which sounds curious until you learn that Br Leo is a cat.

The brewery is smart and modern, efficient and spotlessly clean. Above the mash kettle and lauter hangs a small wooden figure of Saint Arnold of Metz, the patron saint of Belgian beer, a warm red against the white walls and shiny steel (this was a gift from Keinemans to mark the opening of the brewhouse).

Two fermenters are opposite the brewhouse, with space for a third if they choose to add one. The hot and cold liquor tanks, which are filled with the monastery’s own source of well water, are just behind. There’s a cold room, where the hops are stored; a mill room with sacks of grain and bags of sugar. In the bottling room there are two packaging tanks. There’s a warm room next door for bottle conditioning.

“Everything you hear is a secret!” Fr Mateusz says with his index finger to his lips when I ask about the recipe. But I can tell you that Tynt Meadow uses Maris Otter, British sugar, and some speciality malts. There’s a mix of different English hops, a yeast sourced from a British yeast supplier, and the monastery’s own water. The beer has a relatively high final gravity, which gives it a pleasing sweetness; it’s fermented quite warm which produces some esters; it has at least a week to condition after fermentation, then will have another two weeks in the packaging tanks. Once bottled, it’s stored in a warm room to undergo a secondary fermentation for another few weeks, where it develops its carbonation in the bottle and its character forms more completely, a character which will change and mature over time.

“When I come here, every morning before starting production I pray just a short prayer. It helps you concentrate, to remind me that it’s something more than beer here.”

This may be a monastic brewery, but otherwise there is nothing unusual about this process, no mystery ingredients or special techniques that only Trappist monks know. Perhaps the only difference is that Fr Mateusz will spend any downtime in the brewery reading psalms or praying, and will say a prayer before he begins brewing. “When I come here, every morning before starting production I pray just a short prayer. It helps you concentrate, to remind me that it’s something more than beer here.”

He also reads a blessing to the beer before it leaves the brewery and goes out into distribution. He says it in Latin, and it translates as: Lord, bless this creature beer, which thou hast deigned to produce from the fat of grain: That it may be a salutary remedy to the human race, and grant through the invocation of thy holy name; that, whoever shall drink it, may gain health in body and peace in soul. Through Christ our Lord. Amen.

The blessing I can understand, but as someone who is non-religious, one question nags me throughout my trip: What does praying actually mean?

I quickly realize that prayer is not the dramatized “Dear God, please help me” of Hollywood movies. Nor is it a kind of mindfulness, as prayer is looking outward to others rather than reflecting on the self. “It is the matter of being rather than doing or even thinking,” says Fr Mateusz, and monks try to be “in the presence of God all the time.” The idea may seem abstract to those who don’t have their own connection to prayer, so he offers an analogy which is relatable.

Imagine being in the same house with someone that you love. You don’t have to see them all the time, or speak with them or even think of them, and it’s enough to know that they are nearby. “And in this time you can do many different things,” he says, like read or work or daily chores. “But from time to time you need to meet that person face to face, drink coffee together, chat for a while.” Prayer is that presence, feeling them nearby without needing to be conscious of it, and then taking the time to regularly engage with them. For monks, both the liturgical prayers in the church and private prayers maintain that connection in different ways.

During the liturgical prayers, the 150 psalms are read—or chanted as lyrical poems—on a weekly basis. These prayers are structured and constant, always in the same order, collected together in themes which cover the breadth of human emotion and experience; they express praise and thanksgiving, wisdom and lament, and they help deal with anguish or pain. These prayers bring a monk back into contact with God. There comes a time when a monk knows the psalms by heart, and through that understanding they begin to hear different meanings in those words—much like how the repetition of brewing leads to mastery, and then to freedom—and that helps guide them in their private prayers.

“The content of [private] prayers can be everything,” says Fr Mateusz. “You can praise, you can ask, you can bring other people and their affairs into your prayers, you bring of course yourself into it.” But the most important thing for a monk is the act of being in a constant presence with God, he says. “You put aside everything else to pray.”

For Fr Mateusz, that’s especially important because his work can keep him away from the church. “I try to adjust my brewing job to the life of a monk; otherwise you are a monk for a few days, then you are a brewer,” he says. “I am a monk first of all.”

When the church bells wake me at 3:15 a.m., I keep my eyes closed and sleep until the 4:15 a.m. bells. I want to find my own daily rhythm during my time at the monastery. As the monks return to their rooms after Vigils and continue with private prayers for a few hours, I follow my own version of that solitary, silent time, and I leave the guesthouse and head outside for a run.

I head through muddy puddles, over slick rock, past dewy ferns, bramble bushes, nettles which sting my knees and shoulders—none of this is allegorical, it’s just the English countryside—and find my way to a rolling country lane, without obstacles, and just a white line painted down the middle. I’m not running towards a place so much as a feeling, a point in a run when the muscles have loosened, have gotten used to what’s happening, and my mind follows—it frees, and it flows in a new way. This is both my escape, my freedom, and my way of focusing and thinking.

I hadn’t been able to relax in church for the first day. My mind was too filled with thoughts: what I was doing, questions I wanted to ask, how I might describe things, the work I had neglected and needed to finish. I saw that I was experiencing life like watching it through my phone screen, either absent from it or waiting to take a photo of what was in front of me, instead of being present in the moment.

My head has been busy all year, thanks to my workload, book-writing burnout, running injuries, and an anxiety hangover from lockdown life, and I’ve struggled to find clarity. The monks see things differently, and I try to take something from the way they structure the rhythm of their lives.

On my first run, the landscape was all green, everywhere. But by the end of the week, I notice the depth of colors, the different types of trees and grasses. I see how they blow in the wind from day to day, how one morning’s chilly mist feels different to another morning’s warming sunrise. As I run the same routes, I find more comfort in them, and more confidence in where to go. I know the turns, the hills, when to slow through the overgrown forest and when I can run a little faster. And I know how I feel—I know when my legs feel light or heavy, when my breathing is easy or labored, because running is something I repeat daily, weekly, yearly. I find joy in the routine, and in new discoveries along familiar paths. It’s while running that I begin to understand how this is an analogue of monastic life, and also of drinking the same beer every day.

Like running, there is still movement in this repeated habit. Each evening, I open a bottle of Tynt Meadow with my supper of bread and cheese. When fresh it’s bitter, with some floral hoppiness alongside vanilla, dark plummy stone fruits, raisins, and baking chocolate, with an effervescence of youth. A bottle that’s two years old has prunes instead of plums, dried figs, molasses, dark berries, salted licorice, the umami signature of autolysis, and the complexity of age. As it ages it develops, becoming not something new but in motion, something that can be appreciated differently, personally, but perhaps something that can never be truly understood. What tantalizes us just beyond our reach is what keeps us coming back for more.

Already, by my third morning at the monastery, my mind is clearer. I feel a great sense of calm, especially during Lauds and Compline, when I’m rising into the day or easing into the night. I’m not thinking about the world beyond the monastery, or beyond the rhythm of my day. My world has shrunk, but it has also expanded into a new vastness.

“One of the fascinating things about beer is that this potentially sophisticated beverage is made of the simplest ingredients,” said Dom Erik at the brewery’s blessing, on St George’s Day in 2018. “By being refined to manifest their choicest qualities; by being brought together in a favorable environment; by mingling their properties and so revealing fresh potential; by being carefully stored and matured, the humble malt, hops, yeast, and water are spirit-filled and bring forth something new, something nurturing and good, that brings joy to those who share it. Considered in this perspective, the brewery provides us with a parable for our monastic life, with the Lord as virtuoso brewmaster. The Scriptures favor wine as an image of the Gospel—but that is culturally conditioned; beer, it seems to me, is a much-neglected theological symbol.”

There’s a permanence to monasteries, a constant proximity with God maintained through the rhythm of prayer, a sturdiness of structure, an unceasing hope and anticipation. There’s also the inevitability of change in the world beyond the walls of the monastery, and as Trappists work to support themselves, what they produce needs to be relevant to the people outside.

The monks at Mount Saint Bernard Abbey gave up a practice that had lasted for the whole of the monastery’s existence and started something entirely new. That in itself is the essence of the monastic journey—leaving behind one way of life to commit to another—and it also reflects the renewal of traditions, of life. Now brewing supports their monastery, and people drink their beer and remark how it’s made by monks, and how that’s special.

That perceived specialness makes me wonder if Fr Mateusz thinks the beers are touched by a divine essence. “I like to think about that,” he says. “When I was a beekeeper in Poland, a lot of people said, ‘Your honey is special.’ There were three other beekeepers in the village so the bees are taking nectar from the same flowers. It’s impossible to say these are the monastic bees and they are flying only here and my honey is special, but a lot of people say that this is special. When you work from the depth of your spirit, you can transmit somehow what is within you.”

Fr Mateusz is one of the only brewing monks in the world, and he’s found a way to balance his life of prayer with making Tynt Meadow. “I really enjoy this job, and I can testify that you can do it within your monastic journey,” he says. “I learned a lot of myself by working here. Coping with stress, suddenly fermentation stops, something is wrong with bottling.”

I don’t know if Fr Mateusz said an extra prayer on the morning when the labeler was sticking, but for the rest of that day, and for four more hours the next day, we filled over 11,000 bottles without stopping, flowing in the easy rhythm of opening a box, grabbing bottles, filling the box, closing it, placing it on the pallet, opening a box, grabbing bottles, filling the box, until the church bells rang once more.