A few weeks ago, we lived in a different world. Since then, as the novel coronavirus has continued spreading rapidly across the globe, most facets of daily life have changed. Our routines have been disrupted, our freedom of movement curtailed. Even our simplest quotidian habits have shifted in an effort to stop the spread of the virus.

Those experiences are felt particularly strongly for those of us who live in big cities. Because the virus is so contagious, our regular gathering places—restaurants, bars, coffee shops—have had to close, or significantly change how they function. Some businesses are staying open, others can’t, and others don’t see the point. While it’s imperative that people distance themselves from others, small businesses are suffering terribly. A few days of low or no sales are enough for many to consider shutting down for good.

I’ve been self-isolating in the face of COVID-19 since Friday the 13th, a spooky coincidence that feels like it belongs in an episode of “The Twilight Zone.” Save for the few trips to buy necessary provisions, I’ve stayed put in my Chicago apartment, trolling social media for new information and feeling overwhelmed by the number of tip jars and GoFundMe campaigns already springing up in the face of massive, government-mandated shutdowns that have disproportionately affected those working in the service industry.

So when I checked my Venmo account and found $200 I didn’t know I had, I knew what I was going to do: visit my local spots, stay six feet away from people, and spend money to show support.

[Editor’s note: This story was written in advance of Chicago’s shelter-in-place rules, and delivery is the best option for supporting local businesses.]

In whichever way you can be a regular in a big city, I am. I like to stick to my neighborhood circuits and routines. Before I moved to Chicago, I lived in Oakland, California, and could claim that I worked in five different cafes, restaurants, and breweries in a nine-block stretch. I often end up getting hired by the places I frequent; bonus points if they’re within walking distance of my apartment. This has made the slowdown in local businesses even more personal—many of the folks suffering are my friends, my colleagues, and my former employers.

I texted Ria Neri, owner of Four Letter Word and Whiner Beer Company, a few days ago to ask how she was doing. On Saturday, March 14th, she reported that the cafe was busier than usual. The following Tuesday, things had changed.

I worked at Four Letter Word when it opened in the fall of 2018. It’s the coffee shop I tell everyone to go to when they visit the city. Alongside Cellar Door Provisions (a small restaurant that serves gorgeous dishes—to call it “farm-to-table” trivializes how wondrous the food is) and Diversey Wine, Four Letter Word completes the triangle of my three favorite Logan Square businesses.

“It’s definitely a day-by-day, hour-by-hour kind of thing. Just maybe like three, four days ago, it was great. People were coming in—it was like a normal day and we were actually busier than usual.”

“I'm a little stressed, you know, but, um, it's…” Neri is struggling to figure out how to articulate her feelings. “You know, it's been OK,” she finally settles on.

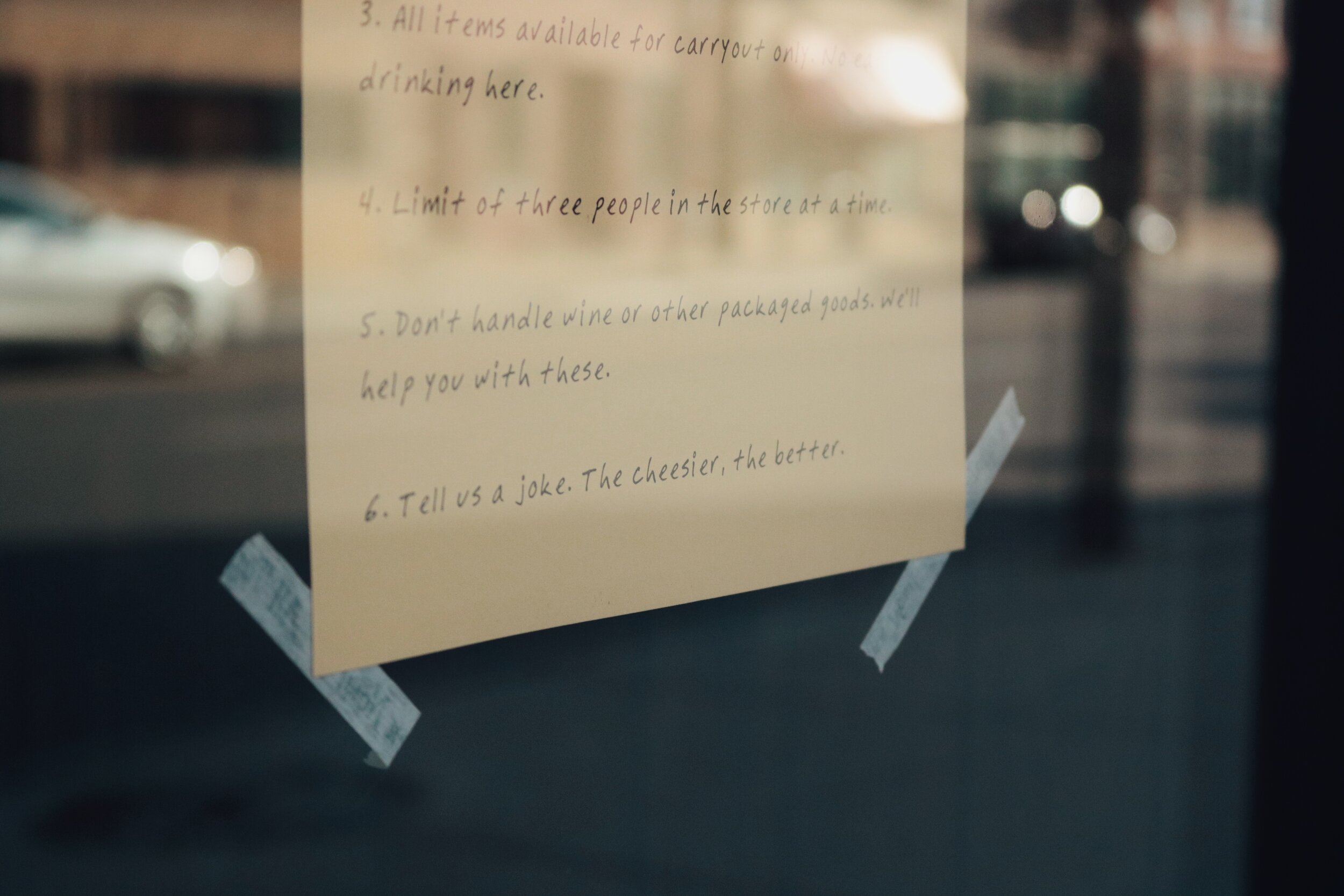

There are now handmade signs taped up throughout the cafe: “No more than eight people inside.” “Please don’t pick up bags of retail coffee unless you know what you want.” “Hey! Here’s some sanitizer!” Today will be an exercise in reading, and in following the rules.

“It's definitely a day-by-day, hour-by-hour kind of thing,” she says. “Just maybe like three, four days ago, it was great. People were coming in—it was like a normal day and we were actually busier than usual. When the governor announced what was going on [in Executive Order 7, halting all on-premise consumption at bars and restaurants], it was a little relieving for me.”

Four Letter Word has since converted its service to a to-go model. All drinks are served in disposable cups. A customer walks in and I watch as the barista pulls a shot of espresso and pours the drink directly into a small white cup. My own coffee-pro sixth sense goes haywire for a minute—I’ve worked in many places where to-go drinks under five ounces are explicitly prohibited.

Neri is unsure how long Four Letter Word will operate in this way. “I'm in between closing completely or just keeping with grab-and-go,” she says. “[I’m] seeing the support of people coming through and the tips they give, but balancing [that with]—what is the responsible thing to do? To the public, you know? It's a struggle every day, trying to figure out the right thing to do.”

As I’m about to leave, I run into Matt Eisler and Kevin Heisner, co-owners of Heisler Hospitality, a hospitality group that runs a number of bars and restaurants in the city. I know Heisner—he designed the interior of Four Letter Word’s cafe space—but this is the first time I’ve met Eisler, and they’re having a quiet conversation when I say hello. They say that they’ve shut down seven of their businesses, which are all bars without food programs, so switching to a takeout model isn’t an option.

“Really, we’re just waiting for the government to do something,” Heisner says. As we chat, it’s hard to tell if they’re hopeful, or if hope is too painful at this point—every corner turned is met with a new hardship. The uncertainty feels the most dangerous: will this last one week? Two weeks? Months? There’s a perceptible weight on their shoulders, and I can’t offer any solace.

As I cross the street, I realize I forgot to buy coffee—I’m already failing at my task. I make a mental note to buy some beans online.

[Note: On Thursday, March 19th, Four Letter Word announced it would be closing its retail location. You can still buy whole-bean coffee and merch online. I ordered coffee for my friends, Jeff and Steph, a few days later. $18.50 + $6 for shipping. I put $20 in the virtual tip jar to benefit the baristas.]

I decide to peek into Diversey Wine, the natural wine store located across the street. As I pass Cellar Door, I spot a new sign on its window: “Closed until further notice.” There’s a delicate heart drawn below.

When I first moved to Chicago from Oakland, I used to say that Cellar Door was the most California restaurant in the city. Turns out that one of its co-owners, Tony Bezsylko, also moved to Chicago from California with, as the restaurant’s website describes, “a bread shaped hole in his heart.”

A lot of the staff members at Cellar Door would come to Four Letter Word throughout the day to grab a coffee, but Bezsylko’s lightness truly made me pause and reconsider the way I approached customers. I remember one conversation when we rambled about power structures and supporting workers—I can’t recall what spawned it, but it made me think, “This is a leader.” His kindness is transformative.

I peek into the windows before turning around. I had planned to go to Diversey, but I can’t. I’m not ready for this quite yet.

After sitting in my car for a few moments, I remember the routine my boyfriend made me promise to follow: after any interaction, wipe down all surfaces, wipe down the steering wheel, wipe down anything you carried in and out of the car. I whip out my disinfecting wipes, and then I’m ready to go.

Feeling defeated by the fact that I have yet to buy anything, I head over to The Hopewell Brewing Company, which is just a short drive away from the triangle. As I park my car, I catch myself thinking: do I have to pay for parking? I’m at a metered parking spot, but the absurdity of this current moment has me second-guessing basic societal rules and established laws. Of course I have to pay for parking. Are other people going to keep following the rules?

Inside, there are two bartenders behind the bar—and no one else. Four Letter Word had removed all the seats in their cafe, so while the space felt empty, it also felt like you could still move around. All the seats at Hopewell are pushed into tables or the bar, save for a few holding staff members’ jackets and bags. It’s a reminder that no one is coming in for a while.

“It's only been a couple of days so I'm not sure it's really, totally set in what it's going to be like,” says Cress Wrenn, Hopewell’s taproom manager. “It's a huge part of our business, our taproom sales. So we're definitely still wrestling with what those numbers are going to look like and what it'll take for us to stay afloat.”

Just moments after I arrive, one of Hopewell’s co-founders, Samantha Lee, walks in with a box of plants and some coffees from Stumptown, which has closed down its retail space in the lobby of the Ace Hotel in the West Loop.

The plants are for a photo shoot Lee’s setting up with Hopewell’s canned beers and merch. “We have a lot of friends in New York. I think right when the announcement [to close bars and restaurants] was made, all of our friends bought something or left a virtual tip,” she says. “That's been really great. It's been really nice to see that people are speaking up for us on our behalf too, and hopefully went out and voted.” She’s sporting a wristband with the words “I Voted” emblazoned in blue letters. Some things are still normal.

“I would say 80% of our business is from restaurants and distribution, taproom included,” she says as she arranges small cacti and succulents around colorful cans, making the already appealing label designs look even more luscious and lively.

“Even if we can ramp up to-go sales, there's just no way that we can match those numbers at all,” she continues. “So just thinking about like, ‘Okay, well that's the fact of the matter. So now, what do we do?’”

“It’s a huge part of our business, our taproom sales. So we’re definitely still wrestling with what those numbers are going to look like and what it’ll take for us to stay afloat.”

The uncertainty comes up with everyone I talk to. There have been some wage cuts, but for now, everyone still has their jobs. But the question still looms: what’s coming next?

I’ve been on this journey too long without buying anything. I go up to the bartender, who’s wearing gloves the color of a nurse’s scrubs. I purchase a four-pack of Good Eye, a Zwickel Lager whose website descriptor instructs consumers to “Drink now!”, and a bottle of Neon, the third in a series of pét-nat-inspired, mixed-culture sour ales. This edition has blackberry and lemon peel and is a deep maroon—it’d be easy to confuse with wine, especially since it comes in a 750ml bottle.

Another patron comes in as I’m about to buy my beer. I ask if I can take a picture of him carrying his beers, and tell him I’m writing about my favorite local spots. He asks for which publication, and says, “Yeah, I know Good Beer Hunting!” He’ll tweet about it later.

The beer is $30, and I tip $20. I’m a quarter of the way there.

As I leave, someone yells, “Oh yeah, Happy St. Patrick’s Day!” Everyone laughs, echoing off the high ceilings.

My hands are starting to get dry from using so many disinfectant wipes.

When my boyfriend gathered supplies for a potential quarantine last week, I balked at what he purchased. In his haul was pasta, frozen peas, and chicken. I asked him, “How are we going to cook all of this?”

“What do you think is happening?” he asked.

On the way to Middle Brow Bungalow, I call a person who’d understand this reaction: my mom. Growing up in Miami, Florida, we were used to disaster prep, but for a different reason. A hurricane scare is expected at least once a year, and every half-decade or so the threat is real enough to take seriously. To prepare for a hurricane is to prepare for power outages and lack of access to clean water—it’s normal to have a generator in your garage and a bathtub full of water ready to go, plus canned beans and other provisions that require no cooking or heat.

My mom understands the threat this pandemic poses, but clearly hasn’t read Twitter as obsessively as I have. “At least with hurricanes, it’s not like the whole world is going through it,” she says. “And at some point, you know it’ll be over.”

Before I pull up to Middle Brow, I decide to stop at Damn Fine, a “Twin Peaks”-themed coffee shop, if you can believe it. I had last visited on Friday, and now I’m feeling in need of coffee.

“As soon as I heard about this virus and what it was doing and why it was dangerous, I started thinking, ‘This is coming here and it’s going to totally disrupt everything.”

I’m met with a sign saying the shop has closed for the time being. I’m sad, but I’m not overwhelmed like I was when walking past Cellar Door. It’s as if my feelings have already adjusted to this new normal. The pace of change is the same as the pace at which we consume information—the state of the world evolves with every click, every swipe, every time I put the car in park.

When I pull up to Middle Brow, I’m met with a plethora of produce. “One of our purveyors got in touch and said she had a bunch of vegetables that would go to waste,” says Pete Ternes, the delightfully charming co-owner of the business. Middle Brow is just as much a brewery as it is a restaurant, dishing out pizzas and baking fresh bread that’s become a staple in my home.

Ternes exudes a warmth that is both comforting and authoritative. “Thank you for waiting over there,” he says, smiling and waving to me as I wait about 10 feet behind the folks next in line. Middle Brow is lined with French doors, and today business is being done through one of them. “Did you see the guide I made for people to line up?” he asks. I look down to see chalk lines scribbled on the tarmac, squares spaced far away from each other, numbered 1, 2, 3, 4.

“I did a segment on the ‘TODAY’ show,” he laughs, acknowledging the silliness of that statement.

“I'm watching the segments before mine, and those segments are showing all of Europe shut down ... And then my question was about like, will there be any leadership from private insurance companies to cover this as a business interruption?” he laughs again, this time at the absurdity of the sentiment. “Like, there's no way private insurance companies can even keep up with what's about to happen.”

Ternes balances both the severity of the situation and the necessity to keep trucking on. “As soon as I heard about this virus and what it was doing and why it was dangerous, I started thinking, ‘This is coming here and it's going to totally disrupt everything,’” he says. “And I started emailing my staff and they were laughing at me and I said, ‘Start setting money aside and start buying toilet paper—slowly, don't hoard it.’”

Middle Brow has totally shifted its service model. Just a week ago the taproom was bustling—it’s a popular neighborhood spot and was one of the places I insisted on taking Claire Bullen, our editor-in-chief, when she visited from London. It’s effortlessly cool and has become part of most Chicagoans’ repertoire of fun spots for a casual bite. Like most restaurants, it has since converted its service to to-go orders and beer delivery. Unlike most restaurants, it’s also giving away groceries for free.

Back to those dozens of bags of produce lined up on tables on the patio. Martha Bayne of Soup & Bread and Common Pantry found herself with piles of produce with nowhere to go—so she teamed up with the folks at Middle Brow to distribute them to community members. As people pass the tables, volunteers yell at pedestrians to pick up a bag. “They’re free!” one yells.

The bags are full of kale, squash, and banana peppers. “Not bananas?” one passerby asks. “No,” Bayne responds, “but we have bags of apples and pastries!”

“Is this because of coronavirus?” another person asks, walking by but stopping after a volunteer waves them over.

Ternes says he’s communicating with his staff once a day, and that shifts in their daily operations are also focused internally. “We're offering staff meal twice a day. So we're trying to get folks to sign up so we know how much food to make. One of our managers made a bunch of spreadsheets that say like, ‘What symptoms are you feeling?’ Or, ‘What skills do you have that you can offer someone else who needs, like an oil change?’ We have people on our team and they can come do that for you. Everyone's working together to make this as painless as possible.”

I initially wanted to buy bread, but the loaves are all sold out. Seemingly overnight, Middle Brow was able to divert efforts to online ordering and beer delivery. The only thing left for me to purchase is a bottle of wine.

How did Middle Brow adapt its model so quickly? “The short answer is that I believed it earlier,” Ternes says. “I started preparing for it as soon as it looked inevitable. We had things pretty much ready to go.”

I watch as he explains the wine offerings to a customer who says he’s been laid off—he works in the service industry—but it’s his girlfriend’s birthday and he wants her to have something nice. Ternes describes each of the wines viscerally, and it’s almost impossible to choose because he’s made each sound so delicious. I decide on a wine from a female producer in California named Martha Stoumen, who I fangirl over on social media. It’s $29 dollars—I tip 30%.

My last stop is All Together Now.

There are no free parking spots in front of the store, just metered parking. A man comes up to the parking meter vestibule, pulls out gloves, and begins pushing buttons to add money to his meter. “I’m sorry this is so weird-looking!” he yells. I decide to call my boyfriend, and I read the meter number and ask him to pay for it at home. I am not as prepared as this guy.

“If I could wear a disinfectant wipe dispenser around my waist, I would,” says Jeremy Patenaude, ATNs general manager. When I visited a few days ago, Patenaude was wiping down surfaces obsessively. The threat of coronavirus still felt far away, but we were both rubbing down anything we had to exchange between us during a normal transaction. I took out my credit card, gave it a wipe. He swiped my card, rubbed down the iPad for me to sign. I took my card back, rubbed it down again. The entire transaction took us an embarrassingly long time to complete.

But now, that’s business as usual. “Just call me Captain Disinfectant,” he says.

“I’m in a stupor. It feels very surreal. Like I’m living through a bad movie. Today is good. I feel like I have good days and I have bad days. They’ve been alternating so far, so now it’s getting pretty easy to predict.”

The changing circumstances mean that ATN is, strangely enough, implementing ideas its team had thrown around in the past, like a fixed family dinner (every night they announce the day’s offerings and folks can call in to order) and a wine and cheese hotline (which people can use to purchase a cheese plate and wine pairings).

“Since we just opened, for the past year and change, we've been throwing different things at the wall to see what sticks,” says Erin Carlman Weber, one of ATN’s co-owners. “We've essentially been trying out new concepts and new initiatives for [the whole time we’ve been] open. So I think that left us uniquely positioned to kind of hop to something different or think about doing something in a different way.”

ATN has responded swiftly to change, including opening its front windows for pick-up service. That doesn’t mean things aren’t scary. I’ve known the folks at ATN since its early days, so maybe Carlman Weber is being slightly more open with me, but she’s the first person who has made me feel like it’s OK to be anxious about the future.

“I'm in a stupor. It feels very surreal. Like I'm living through a bad movie. Today is good. I feel like I have good days and I have bad days. They've been alternating so far, so now it's getting pretty easy to predict.”

I try to get their nightly dinner, which is sold out, so instead I buy another bottle of wine to join the collection. I reason with myself that spending money is good, and stocking up on wine is OK—it’s not like it’ll go bad. Another $29 charge, another disinfectant wipe-down dance. I use my pinky—believing somehow that this digit is less prone to picking up the virus—to tip 30%.

I start to realize there might be a horizon coming on this kind of spending.

When I get home I realize I forgot to swing back to Diversey to get (more) wine.

Luckily, Diversey is doing delivery and pick-up. Inspired by our recent b-Roll series highlighting the drivers and delivery people bringing us cases of beer and bottles of wine during our periods of quarantine and isolation, I decide to call in an order for delivery.

Before I pick up my phone, I pause. Diversey’s delivery service has an email option, and yet I’m choosing to talk on the phone, to a human. While I play on a seesaw between “introvert” and “extrovert,” I definitely find more joy in spending free time by myself rather than with others. When my boyfriend was on vacation for eight days, my friend asked me if I was bored. With chicken nuggets broiling in the oven, I texted back, “I’ve never been bored by myself, ever.” I didn’t text her back the rest of the night.

But right now I really, really want to talk on the phone. Five days of social distancing is starting to have an effect on me, and the excitement of talking to someone other than my boyfriend feels akin to discovering a new series of the “The Great British Baking Show” has popped up on Netflix.

I dial and ask for whatever $100 will buy me. I’m aware I’m going over my budget. But I can for now—and I know everything is going to my most cherished local businesses—so I will.

After the person on the other line talks me through some options, I ask, “Is this Ann-Marie?”

Ann-Marie Meyers and I used to work at Café Marie-Jeanne, another neighborhood spot, where I was a food runner. “I’m a really social person, so this social distancing has been really hard on me,” she laughs, but she’s being serious. We chat for a moment, and then she tells me that my order will be ready tomorrow.

My phone buzzes. “I’m seven minutes away!”

I’ve been meaning to chat with D.J. Piazza, my friend making delivery stops for Diversey, this entire week, and this is the first time we’ve connected. As I pull on my jacket, a familiar question runs through my mind: is it OK to go outside?

Yes, it is. It’s like how parking rules still apply—but there’s still a moment when you second-guess the rules. I’m struggling to adapt to this shift, when some of the most fundamental things about life suddenly feel unstable, and you expect everything to change. That’s not how it works.

“Everyone has been really nice to me,” Piazza says. He’s jovial, leaning on the gate in front of our house as he shows me and my boyfriend the technique he’s developed to give people their deliveries safely (he holds from the bottom, and instructs people to grab from the top). He’s wearing a baseball cap with a picture of his brother as a pee-wee football player—he can’t be more than 14 in the photo. “For Christmas, one of my friends got me this hat, and also gave my brother a coffee mug. Both have pictures of us as Pop Warner football players.”

I head out for a walk around the block with Piazza. My boyfriend, holding our dog, Gordie, waves his paws as a way of saying goodbye.

It’s the first time I’ve strolled around the neighborhood in almost a week, and I make sure to walk a few paces behind Piazza—something that would have looked batshit even just a couple weeks ago. We yell our conversation back and forth, making sure to keep the requisite social distance.

We talk about the variety of responses to the COVID-19 crisis that we’ve seen from our past and current employers. One of his former employers, a restaurant, laid off all its staff in an impersonal email from HR, while his other part-time job at The Stop Along, a casual burger and pizza spot, gave the entire staff two weeks off with full-time pay—and Piazza doesn’t even work full-time.

“We’ll all remember who was shitty to their employees when this passes,” he says.

As I head back to my apartment, I see someone on the street walking their dog. My immediate reaction is to turn the other way, but this person is far enough for me to get around them safely. I loop around and remind myself it’s OK to be outside.

During this exercise, I spent more than I intended (around $270, including gratuities). I bought no food, a bunch of beer, and way too much wine. None of what I bought is what I need—it's chaotic spending, wanting to throw my money at my neighborhood spots, the places I've come to love, the spaces I'm nervous might not be there when this passes.

As I prepare to coop up for as long as needed—it could be weeks, months—the uncertainty weighs like a heavy jacket. Yesterday was sunny, but today is windy and overcast. The changing weather conditions feel like a novelty, and I’m unsure when this will all feel normal.

I round the corner, and go for another lap. I tell myself that it’s OK to be outside.