I fondly remember the first time I met Randall the Enamel Animal. It was the summer of 2008, and I was at the Blind Tiger Ale House—still one of Manhattan’s best beer bars. Dogfish Head had organized a special event to showcase Randall, a towering, cylindrical water filter with a single mission: to alter a beer’s smell and taste.

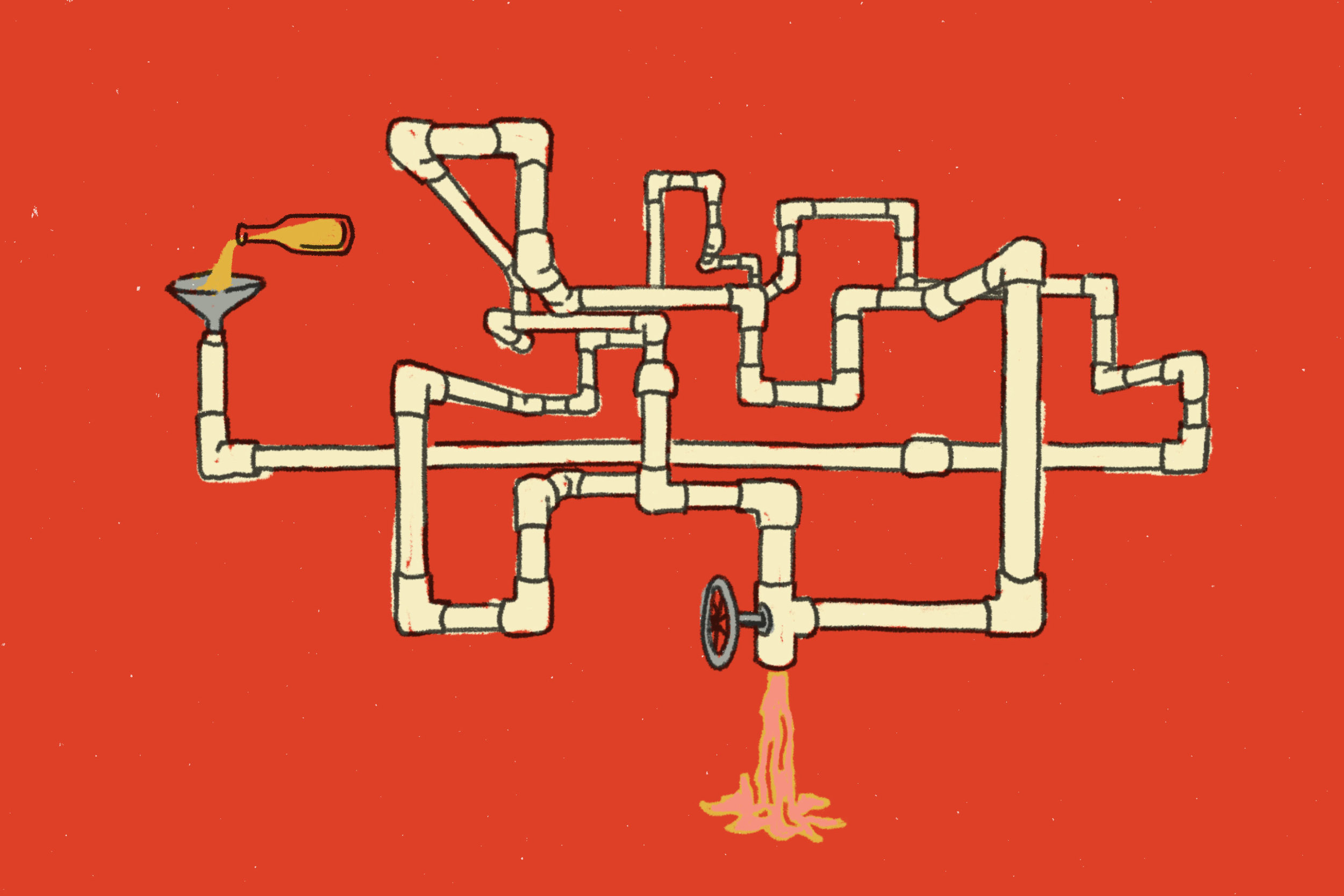

Six Randalls were stationed at the bar that afternoon, each one stuffed with a different blend of herbs, candy, spices, and other ingredients. They were attached to tap lines pouring Dogfish Head’s imperial-strength 90 Minute IPA; when the beer flowed through each Randall, the alcohol acted as a solvent and stripped the natural oils and chemical compounds from the flavoring agents, creating instant infusions.

There was a julep option, filled with fresh mint leaves and bourbon ball candy. A Thai version contained lemongrass, and the “Italian seasoning” Randall featured roasted pine nuts and dried oregano. Doing my journalistic duty (I was reporting for the now-defunct Gourmet magazine), I sampled beer from each Randall. I was most impressed by the “hoppy giant”: whole-flower Warrior and Columbus hops delivered intense aromatics, transforming 90 Minute into a fresh-hopped IPA—the Yakima Valley by way of Lower Manhattan.

“That’s what’s great about a Randall,” Alan Jestice, then the Blind Tiger’s operating owner, told me at the time. “It’s not meant to transform a beer. It amplifies beer’s natural flavors.”

Beer isn’t often treated like gas-station coffee, customizable with a spread of sweeteners and creamers. Add that Splenda and hazelnut-flavored half-and-half, my friend—those are your taste buds, not mine. Tweaking a finished beer’s flavor, though, may seem like a break with the natural order, akin to tacking on a different ending to a novel. Beer is presented to consumers as a finished product, four or five or even 15 ingredients simmered and fermented into a cohesive whole. What you get is largely what you drink. Don’t like it? Buy something else, buddy.

However, one person’s heresy is another person’s opportunity to innovate. Whether for educational or taste-elevating purposes, breweries and companies are constantly inventing new techniques and tools to help consumers reshape and reimagine their beer. A pint doesn’t always sit at the finish line of flavor. In fact, sometimes, it’s perched on the starting blocks—ready to race in unexpected directions.

Randall’s origin story started with a competition. In 2002, Dogfish Head founder Sam Calagione had a hunch that extra aromatic oomph would help his brewery win the Lupulin Slam, an event that pitted East Coast breweries against West Coast heavyweights such as Russian River and Pizza Port, as well as Colorado’s Avery. Dogfish Head created Randall the Enamel Animal as a secret weapon, filling it with whole-leaf Cascade hops and pouring 120 Minute IPA through the device.

“People fell in love with it,” Calagione says of his winning entry. “Three of the five other brewers on the stage with me said, ‘I want to buy one of these. Make me one, make me one.’” Dogfish Head decided against trademarking or patenting the Enamel Animal (so-named because consuming super-hopped, resinous beer can feel almost gritty, the sensation like abrading teeth enamel). “Our hope was a bunch of other breweries would embrace it and it would be more widely used,” he says.

Initially, the brewery facilitated Randall’s viral spread by sharing details of its design online, akin to publishing open-source code. (The brewery now offers prefabricated Randalls on its website, and Calagione estimates that Dogfish Head has sold more than 500 to bars and breweries across America and the world.)

Though Randall was initially developed to amplify hop aromas, Dogfish Head soon discovered other applications for the device. “Within months we were like, ‘Let’s try it with coffee beans and cocoa nibs in our Chicory Stout! Let’s try it with orange peel and chipotle peppers in our Burton Baton!’” Calagione says.

To brewers, the experiments were a blast, but their biggest value proved to be consumer edification. A beer’s main ingredients are not as transparent as, say, a pizza’s: there’s the dough, the tomato sauce, the cheese, the pepperoni rounds crisped and curled up into oily cups. In a beer, there’s no way to physically see the amount of hops that have been used—they leave behind only invisible fragrance and flavor.

“We loved the idea of consumers getting to see and know the ingredients that affect the aromas and tastes of beers at the point of consumption,” Calagione says.

Most people baby-step into craft beer with IPAs, he continues. “They generally know, ‘Oh, it’s a style that’s a little stronger and more emphasizing of hops,’ but they don’t really get what hops are. By doing Randall nights where consumers can touch and smell hops…you see people having that lupulin epiphany: ‘I get it now. I see how diverse hops can be.’”

A Randall can also make the foreign more familiar, or at least less frightening. Recently, Calagione attended the Extreme Beer Fest in Boston. During the welcome event, Dogfish Head poured the tartly refreshing SeaQuench Ale (a mash-up of a Gose, a Berliner Weisse, and a Kölsch) through a Randall stuffed with Sour Patch Kids.

“In general, non-beer-geek consumers hear ‘sour beer’ and think ‘sour’ is a negative connotation,” he says. “If you take a sour beer and run it through Sour Patch Kids, people are kind of like, ‘Huh, OK. That’s a candy. I don’t know if I like sour beers but I like candy.’ Then they try them together and they’re like, ‘Holy shit, that’s good. Now I want to try a regular SeaQuench.’”

Homebrewers can also mess around with flavor additions thanks to Indiana’s Blichmann Engineering, a design and engineering firm specializing in high-grade homebrew equipment. Founder John Blichmann likes to create products that simplify brewing and fill a need.

“There was no easy-to-use way to infuse hop aroma into the beer without losing aromas,” he says.

“It’s like a Jolly Rancher in a glass. It’s a nice presentation, having a pink or green beer.”

This was in the early 2000s, a time before excessive dry hopping became all the rage. Blichmann started tinkering, and eventually developed a bullet-shaped device named the HopRocket. The pressurized, stainless-steel device, which Blichmann says was released around 2005, is a homebrewer’s multi-tool. It can be used as a hopback, adding heightened hop aromatics during brewing; as an effective filter; and to flavor beers prior to serving.

“You can load it with just about anything,” he says. “We’ve got local breweries that take ground coffee in a little hop bag and can infuse coffee flavors. You can do it with hops to add extra hop flavor. The neat thing there is they charge you an extra buck, and you get this fresh-infused whatever.”

Running a beer through a Randall or HopRocket packed with candy is a minor modification, like kicking up a bowl of chili with a few splashes of hot sauce. The goal is to accent and emphasize flavors without wholly transforming the beer itself.

But Peter Hanley was in the market for a total transformation. Around 2013, after more than 30 years in the corporate sector, including a couple-decade run at Kodak, he was looking for a career change. He had read about the New York State Farm Brewery license, which incentivized breweries to use state-grown grains and hops. “I decided to reinvent myself by growing hops,” he says. Though he had no farming experience, he took classes, tested his soil, and founded a hop farm in the Finger Lakes region, growing four varieties across two acres. The plan was to expand to 30 acres, but another idea started taking root. (The hop farm remains operational today.)

Whenever his adult kids visited, they raided his fridge for craft beer. Back home, he says, they’d buy Natural Ice and PBR. “They wanted the craft-beer experience, but they didn’t want the price tag,” he says. It got him thinking: how could he create more affordable, yet still highly delicious beer—beer that could be as individual and customizable as coffee?

He embarked on a nearly three-year journey experimenting with stovetop recipes, FDA-approved co-packing labs, and flavor suppliers to create Mad Hops: flavored drops made from hop oils, malt, a bittering agent, and flavoring concentrate. They’re packaged in small plastic bottles, about the same size as a miniature tube of sunscreen. The idea is to squirt several drops of, say, wild blueberry into a cheap, industrial Lager. “Our fruit flavors basically mask the beer,” he says.

“By doing Randall nights where consumers can touch and smell hops…you see people having that lupulin epiphany: ‘I get it now. I see how diverse hops can be.’”

Hanley envisioned Mad Hops as a millennial bridge between budget and craft beer. Only got enough money for a 30-pack of commodity lager? Great! Mad Hops can make the cheapest IPA this side of the supermarket. However, retail sales flopped worse than a second-rate soccer player. “Our biggest challenge is awareness, that you can do this to beer,” he says. “It’s not intuitive.”

Instead, Mad Hops mostly does business online, catering to a niche of light and non-alcoholic beer consumers craving flavor without the calories and extra alcohol. That would have been a totally brilliant business plan in 2010. Now, breweries big and small make highly flavorful low-calorie and booze-free beers. “Believe me, I’m not thrilled about seeing those things because they’re our stake in the ground,” Hanley says.

Now, he’s looking to break new ground in bars. He recently rolled out a system designed to infuse flavors directly in kegs of beer. The device, essentially a hose and couplers that connects a Mad Hops bottle to a keg, flavors 15.5 gallons in about a minute. The idea is to take a low-cost Lager and doctor it, offering customers house-branded “light craft beer” priced somewhere between a domestic Lager and the latest IPA. (Because the beer is altered before it’s dispensed, bars can’t use a brewery’s branding.)

Hanley has signed up bars in New York and Florida, but, at this stage, it’s hard to know how far this idea will travel. Laws are persnickety and piecemeal nationwide, and perhaps some brewery will create a compelling, and compellingly priced, alternative. The idea may also strike consumers as just plain strange. “My challenge is to let the world know that you can flavor beer,” Hanley says.

Flavoring batches of beer with concentrated hop oil is a pretty standard practice in the brewing industry. Flavoring your own beer with hop oil, well, that’s a legend that dates back to Bert Grant: a colorful figure who founded Yakima Brewing & Malting Co. in 1982—America’s first brewpub since Prohibition.

In order to always have a bitter jolt close by, Grant allegedly traveled with a small flask of concentrated hop oil. Whenever he was served a drab domestic Lager, he supposedly spiked the beer with his personal supply. Ta-da! Extra IBUs, a hoppy Lager of his own, aftermarket creation.

“As soon as I got involved in beer, I heard that story about Bert Grant,” says Dave Selden, the creator of the 33 Books series of tasting journals and kits. “That was so metal. It’s just cool to carry around a little vial of hop oil.” The legend had long rattled around Selden’s brain, as did this idea: wouldn’t it be fun for drinkers to dose their beer with different hop varieties, creating a choose-your-own aroma adventure?

Selden started buying Hopzoil, an undiluted essential oil derived from fresh hops, steam-distilled in fields during harvest. Each week, he heads to his workshop to mix up batches of what he calls Bert’s Beer Baster, in a nod to Grant. He dilutes five different varietal-specific formulations of Hopzoil—including tropical Azacca and citrusy Centennial—with a custom, alcohol-based mixture that helps it disperse in beer. The blend is then carefully poured into 15ml glass bottles outfitted with medicine droppers.

Squeeze the rubber top to suction up amber hop concentrate, then add it to your favorite (or most loathed) industrial Lager. Each beer becomes a liquid lesson plan. “It’s learning what Azacca tastes like, or Amarillo,” Selden says. “Beer is supposed to be fun.”

Tweaking a beer might seem to some like a questionable modern hack, the kind you see advertised on a website with too many pop-up ads. Click here for three little tricks on drinking a better beer. Reality is, drinkers have always modified beer.

The German Radler blends Lager with fruit juice or soda, while wedges of lime are a must for most folks crushing a beachside Corona. The Michelada cocktail is a Mexican Lager mixed with lime juice, hot sauce, tomato juice, and various seasonings, served in a salt-rimmed glass.

The Mexican tradition of adding citrus and salt to beer inspired Roger Treviño Sr. to found Twang in 1986. Today, the San Antonio, Texas-based company sells Beer Salts, which are designed for drinkers to sprinkle on top of their pints. They come packaged in miniature plastic beer bottles in both lemon-lime and hot lime varieties. (Anheuser-Busch once partnered with Twang to develop a custom salt blend paired with Tequiza, its now-discontinued Lager meant to mimic tequila’s taste.)

“We quickly learned that not only does this taste great with Mexican imports, but that all domestic Lagers and many Wheat Beers are elevated with a sprinkle of Twang Beer Salt,” Patrick Treviño, Twang’s vice president of marketing and business development, said in a Paste interview.

Historically, Germany’s lemony, acidic Berliner Weisse is served mit Schuss—with a shot of flavored syrup, such as raspberry or herbal woodruff. The syrups temper the style’s sourness, and let drinkers customize their beers to their liking.

“In general, non-beer-geek consumers hear ‘sour beer’ and think ‘sour’ is a negative connotation. If you take a sour beer and run it through Sour Patch Kids, people are kind of like, ‘Huh, OK. That’s a candy. I don’t know if I like sour beers but I like candy.’”

In 1999, John Cochran, who would later cofound Terrapin Beer Co., was working for a beer distributor that carried esoteric offerings including Germany’s Berliner Kindl Weisse. The distributor toed the traditional line, selling the beer mit Schuss. “We would drop it off with little packets of syrups,” he says. “I think most of the people threw them away. They had no idea what to do with them.”

The beer left a lasting impression on Cochran, however, who later founded UpCountry Brewing in Asheville, North Carolina. Last year, he finally tackled the tart style with the bubbly Bob’s Berliner Weisse. UpCountry served the beer in its taproom with a choice of four house-made syrups, including grapefruit-rosemary, honey-ginger, lemon-ginger and blueberry-thyme. “It’s not something that’s new and funky and crazy,” Cochran says. “That’s how it’s supposed to be done.”

[Disclosure: UpCountry is a GBH studio client.]

UpCountry’s Berliner Weisse is a summertime specialty, as is the version at Live Oak Brewing, in Austin, Texas. It offers a range of Austrian-made syrups such as elderberry and blackberry, which lend the beer sweetness and a vibrant tint. “It’s like a Jolly Rancher in a glass,” says owner and co-founder Chip McElroy. “It’s a nice presentation, having a pink or green beer.”

The syrups don’t negatively impact a beer’s head, unlike a lemon or orange slice in a Hefeweizen or Witbier. While a wedge of fresh citrus may be agreeable to both eyes and nose, the acids present in the fruit eradicate foam. “We don’t have lemons,” says McElroy, whose brewery makes a magnificent Hefeweizen. “We don’t recommend it, but we don’t actively discourage it. The truth of the matter is, the places that do it, and people see a beer going by with a lemon wedge or something, they get interested. They want to try one.”

At the end of the drinking day, the consumer is in control—and they have been for a long time, before many of these innovations took off. A brewer’s job is to make a beer to the best of their abilities and ingredients. Customers can decide whether to drink a beer from the can or pour it into a glass. They can choose whether to squeeze in some lime or circle the rim with salt. Modern beer is about experimentation, taking sacred cows and roasting them, then maybe adding the bones back into beer. [Editor’s note: That’s a metaphor, we hope.] If there are few rules about what brewers can add to a beer before it’s packaged, then drinkers should have free rein to doctor a beer without limits.

At its Delaware brewery, Dogfish Head now offers a tour built around its portable, handheld Randall Jr., suited for flavoring as little as 16oz of beer. Attendees get the chance to add everything from coconut and strawberries to herbs, spices, and candy. “You get to do your own mix and create your own Randall experience,” Calagione says. The Randall can turn beer drinkers and bartenders into amateur brewers, custom-designing beers suited to their palates and flavor preferences—no brew kettle needed.

“Taprooms are where people go for experimental beers,” says Calagione, “and what’s more experimental than taking an existing, exotic craft beer and doing something spontaneous with it at the point of consumption?”