At some point during my time with Henry Nguyen, he looked me dead in the eye and said, “I’m not a person that was meant to own a business.”

He’s right. He’s also anxious, neurotic, and indecisive. He’s attention-averse. He’s not even all that interested in making money.

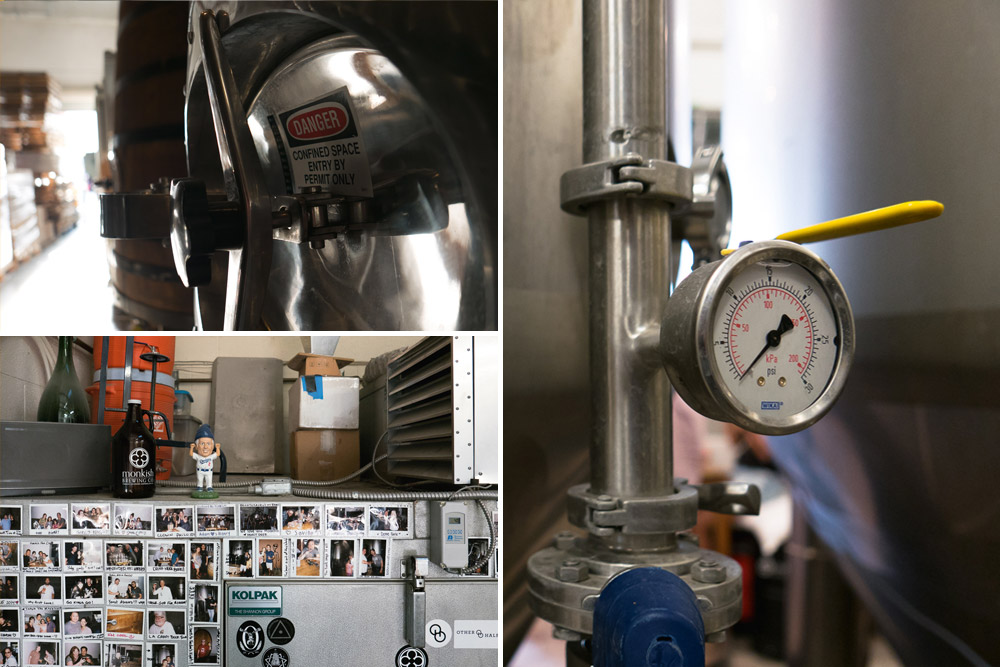

Despite all those things, Henry owns Monkish Brewing Company. Because of all those things, Monkish makes incredible beer. He co-owns the brewery with his wife, Adriana, and they have no investors, which means they decide everything.

When Monkish opened its doors in April 2012 in the South Bay region of Los Angeles, the plan was to make predominantly sour beer. At the time, places like The Rare Barrel and Crooked Stave weren’t quite off the ground—comparable business models were hard to come by.

On top of that, the Nguyens had poured every cent they could muster into buildout, and couldn’t afford even a single barrel. So for the first year, they decided to focus on clean interpretations of Belgian styles—the same styles Henry had fallen in love with while earning a PhD in New Testament Theology at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland.

During that first year, he brewed every batch of beer and manned nearly every shift in the taproom. The old, three-handle kegerator that served as the draft system could only hold two sixtels, which was fine for a while. Once a third beer was added, however, one keg would sit outside the fridge and be rotated in every hour on the hour.

It wasn’t easy. Adriana worked a full-time job at Toyota to support their three children. Henry would take their youngest on sales and delivery runs during the day and brew in the middle of the night. It was the only free time he had.

The closest thing Adriana can compare the experience to is having the first two of those children, only 18 months apart. “Endless sleepless nights,” she says. “You don’t know what time it is. You don’t know what day it is. You’re just going.”

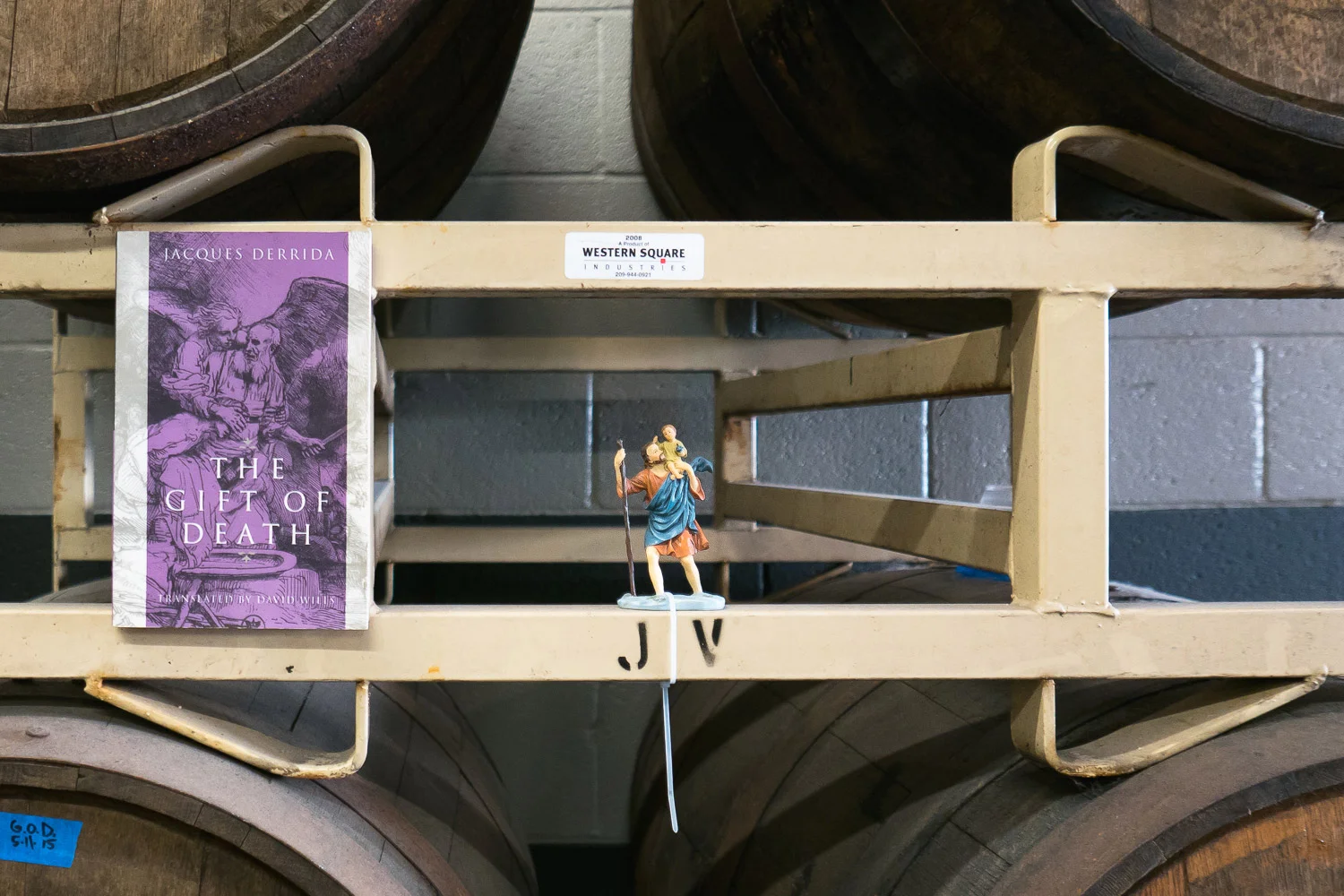

But after their first year, Monkish could afford some barrels and they had a go at the original plan of producing American sours. The thing was, they didn’t turn out that great—at least not according to Henry’s standards. In addition to chronic anxiety, he’s also very much a perfectionist.

“I go in front of a barrel and make this connection—between human and barrel—and try to make decisions in its presence. That’s how a lot of things go around here.”

“We could never get acidity,” he recalls. “The beers were okay. A lot of good Brett character. But we were looking for acidity.”

So they gave it more time.

“We kept saying, ‘Let’s wait another three months,’” Henry remembers. “We’d wait another three months and try it again. Then, after a year and a half of waiting another three months, we decided to forget it. So we do mostly wood-aged Saisons now, and we have a certain method that really works for us here.”

That method, like the business plan, has evolved quite a bit over time. What started out as detailed brew logs and spreadsheets hung on every barrel has been reduced to scrawled-upon painter’s tape haphazardly slapped on them.

“I feel that one of my jobs here is to give the place a sense of energy—to get to know the beer, the barrels,” Henry explains. “And the spreadsheets were the most impersonal thing ever, so I got rid of them. Now, I go in front of a barrel and make this connection—between human and barrel—and try to make decisions in its presence. That’s how a lot of things go around here.”

This is a man who spent days—yes, days—researching the best way to apply a large vinyl decal to his grist case, who is a self-described “calculated decision-maker,” and who renounces data to rely solely on intuition. He’s an exercise in contrasts: calm on the surface but frenzied beneath, a trained preacher turned secular man, a shy public figure, an insecure business owner, and an utter perfectionist yielding to the fickle whims of oak.

In 2014, Henry promoted Jennifer Treu from the tasting room to the brewing deck, naming her Monkish’s assistant brewer despite her lack of professional brewing experience. “I think Henry and Adriana noticed my work ethic,” Treu explains. “And I think Henry wanted to train somebody who didn’t have any previous bad habits.”

By bringing Treu on board, Henry freed up more of his time to focus on the increased operational demands of a growing brewery. The move was perhaps a surprising one, given that he’s a bit of a loner. But taking a pupil under his wing felt like the right move.

“I like that brewing is one of the few apprenticeship jobs that still exist,” Henry says. “You train somebody, they learn the ropes. I really do enjoy having someone here to see if I can impart my philosophy on brewing to them.”

But that’s also an abstract and difficult thing to do. And time consuming in and of itself.

“I’m a really hard person to work for,” Henry admits. “So much of the brewery is built off of feel. It’s hard when you rely on other people to use your intuition, and then they make a mistake.”

“Henry just expects perfection,” Treu agrees. “He expects you to be able to pick up his cues to take control of situations, and that’s never stated outright in any capacity. It’s just something you have to learn from the School of Henry.”

Picking up on those cues, Treu has been an incredibly quick learner. And she’s proven herself invaluable as Monkish has shifted gears and ramped up its IPA offerings, releasing a new beer or two weekly starting earlier this year. Turnaround time from kettle to consumer has been reduced from several months for the Belgian styles, to several weeks for the IPAs, and there’s no way Henry would’ve been able to handle all the brewing on his own.

“Because we’re doing IPAs now, we have to hit a mobile canning schedule,” Henry explains. “So for the first time ever, I’m forced to plan more than two weeks in advance.”

That Monkish makes IPAs at all is a strange thing. For the longest time, there was a sign in the taproom that famously read, “No MSG. No IPA.” It upset some people.

“They didn’t understand why we weren’t making an IPA,” Henry recalls. “I thought it would be funny to make that sign, just joking around with it. But you would’ve thought were talking about somebody’s mom or something.”

What it really came down to was that, in those early days, Monkish needed to focus on its core lineup. That, and they didn’t have any hop contracts. And Henry knew that in order to make the East Coast-style IPAs he wanted to, the ones that were hazy and yeast-driven like his Saisons, he’d need hops that are in high demand. So he started contracting for Nelson Sauvin, Mosaic, and Citra years before he’d actually need them.

Around the time those contracts started taking effect, Henry started dialing in his recipes and quietly took down the “No IPA” sign in the tasting room. In April of this year, he released the brewery’s first IPA, a collaboration with New York’s Other Half Brewing, called First Things First. It sold out in less than an hour.

Monkish’s second IPA, Run the Pigeon, sold out in 45 minutes.

Tickers and traders had taken notice, and so did Los Angeles Times freelancer, John Verive. “The IPAs came out of nowhere,” he admits. “It was the third or fourth weekend they were doing a release and I decided to drive down to Torrance. I drove by the brewery about a half hour before noon and there were 300 people in line in the parking lot waiting for these IPAs.”

And that’s the way it’s gone, virtually every week since. Over the past few months, hype has grown, crowds have swelled. People drive in from Vegas or fly down from the Bay Area. Lines form well before the brewery even opens. A wristband system has been implemented. Monkish has gone from selling 18-month beers to selling 18-day beers, and the people can’t get enough.

It seems especially difficult for Henry to admit Monkish’s entrée to zeitgeist has come through making a style he’d claimed to never brew. But even though his love for Belgian styles continues to be a focus, Monkish is now garnering attention from other corners of the beer world, and they have a lot more eyes on them, all the time.

“They didn’t understand why we weren’t making an IPA. I thought it would be funny to make that sign, just joking around with it. But you would’ve thought were talking about somebody’s mom or something.”

That spotlight is something Henry continues to struggle with.

“I think some people just sell beer and don’t care. I care too much,” he says. “I get too much anxiety with these can releases. I’m not cut out for this.”

He worries about people taking time off of work or traveling great distances without being sure they’ll even get beer. He feels genuinely sad if everyone in line doesn’t walk away with what they came for. But on a couple of occasions now, he’s been the reason they’ve walked away empty-handed.

Three times since April, Henry has cancelled can releases. Once, because the cans themselves weren’t delivered in time to fill, but twice simply because he wasn’t happy with the beer. In those two instances, the beer had already been packaged, with hopes that it would settle into the precise and narrow parameters set for Monkish IPAs. They didn’t. So they were dumped.

The most recent cancellation of More Props and Stunts—a somewhat ironically named beer, given the circumstances—was announced less than 12 hours before it was scheduled to drop. The decision was met with some criticism, especially online. But nothing close to the barrage of hatred The Lost Abbey experienced earlier that same day over their botched release of Duck Duck Gooze. Still, others praised Monkish for their scruples and commitment to quality.

Regardless, those are the types of decisions that add to Henry’s stress. Those are the types of situations he feels grave responsibility for. And the weight of all that responsibility is visible in his face, in his posture.

It’s a daily exercise to balance his sense of obligation to the brewery—and his customers, and his 13 employees—with the obligations to himself. Not to mention those to his family. Such is the price of perfectionism, perhaps.

For every decision Henry makes, Adriana is there: as partner, sounding board, source of balance and guidance. Now that she also works at the brewery full-time, she has a unique perspective into both sides of his life. She readily admits “he’s a stress ball all the time,” both at work and at home. But she also knows there are little things that can help ease the tension.

She remembers a story as the family was moving into their new house. They needed some furniture, so she and Henry went to pick some out. At the store, Henry declined the modest fee to deliver and assemble the piece, eschewing the time and labor saved, in favor of hauling it home and putting it together himself. Just one more thing for him to worry over.

But she sees it differently.

“He’s a hands-on guy,” Adriana explains. “He needs to kind of check out of the brewery sometimes, focus on something else completely. It’s funny. That’s kind of how he got into beer: he needed to check out of teaching.”

Maybe a career change is once again on the horizon. Henry mentions occasional breakdowns, moments when he’ll withdraw from the brewery and contemplate quitting altogether. Sometimes he questions whether or not the brewery has a positive impact, or any impact at all. But other times still, he’ll consider whether beer is even a worthy pursuit, especially in contrast to his previous endeavors.

Toward the end of my last visit, he relays a story of a pastor who described his church as a living organism. Over time, Henry says, the pastor learned that he couldn’t just feed the church what he wanted to feed it. It wasn’t his to decide. It had to tell him what it needed, and it was his job to steward it and feed it what it required.

Henry’s trying to do the same. With his beers, his customers, Monkish, and himself. He’s not quite there yet. And he may never become a person that’s meant to own a business—but he’s feeling his way along, at least. “It all kind of reminds me that this brewery, like myself, has a level of imperfection to it,” Henry says. “I’m a very insecure person, a very shy person, and I think our brewery reflects that.