As the Brewers Association delicately pointed out at this year’s CBC in Philly, America’s craft brewing capacity-to-production ratio in 2015 inched uncomfortably in the wrong direction, hinting at an over-leveraged—in fact, some might call it “overly-optimistic”—view of craft beer’s future. But while some had their minds lingering on foundational materials like concrete and steel, others were pining for the ceremony where they’d hand out those seemingly more precious materials—gold, silver, and bronze.

Do medals matter? Do they move the needle? Do they indicate a brewer’s prospects, or are they simply a triumphant moment in time? The answer is different for every beer maker. But for Brickstone Brewery in Bourbonnais, Illinois, it’s made all the difference in the world. “We didn’t even attend,” recalls co-owner Dino Giannakopoulos. “It never occurred to us that we could medal. Then I got a message that we’d won bronze. There was no one there to receive the award.”

This humble Greek family’s restaurant-cum-brewpub got the critical nudge from Jim Cibak, now Revolution Brewing’s product brewer. At the time, he was waiting for Revolution’s brewpub space to be built out and he was able to spend some time with the Brickstone crew. “They were new to their system, so I came in and helped with things like SOPs and worked with Tommy on some recipe formulations, with a few tips and pointers,” Cibak says. “I suggested they enter the beer in competition because these beers were world class, and they were as good as any I had tasted.”

“When he was leaving us, Jim told us we should submit the Pale Ale to World Beer Cup,” Giannakopoulos recalls. “I thought he was nuts. We figured maybe we would, if only for the feedback from the judges on how to make it better. He was so excited he almost went up to receive it for us.”

That bronze was like the sword in the stone. But part of the feedback they got from the World Beer Cup judges was that the water profile needed tweaking. “They could taste a little chlorine,” Giannakopoulos says.

“Yeah, the water was so important,” co-owner Tommy Vasilakis says. “So we started filtering our water and managing the profile, and that improved the beer. We tweaked that beer 20 or 30 times, adjusting pH and running water analysis a lot more. Our water changes all the time, so we’re constantly monitoring it.”

Later that year, they submitted the tweaked recipe to GABF and won gold. “That year was great because it was a midwest sweep,” Vasilakis says. “It was us, Piece, and 3 Floyds. So it got a lot of people talking about it. Only time that’s ever happened. People were able to try all three Pales Ales in the same market—usually you can never try them all.”

“I brought my father, who never really understood what it was all about. But when he got there, he saw how big it was. He was in tears.”

“We went the second time, just in case,” Giannakopoulos laughs. “I brought my father, who never really understood what it was all about. But when he got there, he saw how big it was. He was in tears.”

About an hour south of Chicago, at the center of its own singular expanse of Illinois’ former prairie, Bourbonnais cuts through wide swaths of grass and former farmland with the typical drag of chain stores and restaurants you’ve come to expect from Midwestern outposts. Despite its French fur-trapping heritage, the city is still pronounced bur-bone-us by some of its older residents—mostly those that moved to Bourbonnais during the suburban dream sequence of the 1970s, when it tripled its population over the next decade before flatlining for the next 20 years. But in 2002, the Chicago Bears made Bourbonais the location of their summer training camp, giving this somewhat static small town another shot in the arm.

“You see some different kinds of cars around here in the summer,” Vasilakis says with a knowing smile.

The group is on its second family business in as many generations in the same spot, both of which seem right-sized for the population. The first, Green Briar, was started by the parents, Ted and Helen Giannakopoulos, in 1996—a Greek restaurant, just north of the main strip on Latham Drive. But once the kids and cousins took over, they started making beer around 2006.

“You see some different kinds of cars around here in the summer.”

“I was commuting back and forth from DePaul, where I was studying computer science,” Vasilakis says. “And Dino was running the kitchen. My sister did marketing for [weekly business newspaper] Crain’s, and George and I got into beer and started homebrewing. It was a big thing to bring a craft brewery down here 10 years ago. We knew the food industry, but people didn’t know what craft brewing really was.”

Brickstone started brewing out of a couple of 20-gallon stock pots and served it all at their own bar at the restaurant. The bronze medal gave them enough kick to get a 10-barrel system wedged into the back of the house, and some bigger fermentation tanks that spread like tree roots, winding back to the cold storage and serving tanks. They also removed some seats in the restaurant, a dicey proposition for any business that counts dollars by asses, and put in a small barrel-aging program.

“We have four barrels over there, and removing the booth gave us eight,” Vasilakis says. “[That] didn’t go well with our parents at first.”

That’s the Brickstone brewpub now. But to understand how this slow success helped build a brand new production brewery, we need to back way up.

“Around 2011, people started asking us to distribute to them,” Vasilakis recalls. “Map Room was one of the first places. But we didn’t know anything about that. Our priority was keeping our taproom customers happy, not putting beer into the market. But after the medals, a lot more people started calling. We started with some bombers, and we did all the sales calls ourselves. But we’re from a small town selling beer in a big market. If they didn’t know anything about GABF or World Beer Cup, then they didn’t know anything about us.”

The Map Room’s Jay Jankowski says there were a lot of tilted heads at first. “‘What the hell is that?’” he remembers customers asking. “So, I'd pour a taste, and as they're sipping on the APA, I'd explain that it’s a new brewery in Bourbonnais, and they'd say, ‘Where the hell is that?’”

At a place like The Map Room, one of Chicago’s premier accounts for any brewery lucky enough to get on early, first impressions like this matter. “By the end of that brief encounter they'd agree it was pretty darn good and order a pint,” Jankowski says.

Like so many small breweries, this early success was personal. “We're talking about roughly 10 years ago when there were only a few breweries in the city,” Jankowski recalls. “Variety is key though, especially when running a little corner bar with 26 taps. Over the years, the father of a very good friend of mine discovered them. He goes there all the time. I would keep hearing about how they just came out with this or that. His excitement has definitely kept them in the loop for me when I’m thinking about which beer is going to go onto line #23 or whatever. Tommy has also played an integral role in keeping them on my mind. That’s all it takes when you make good beer. Just dropping a line once in a while to say hi and let me know what they’ve got coming out.”

The high-touch approach from Brickstone seemed to shorten the distance between Bourbonnais and Chicago for others as well.

“Tommy will deliver it himself when he’s in the city,” says Shawn Thomson of The Twisted Spoke in Chicago. “He’ll bring something new in for us. You don’t really see service like that anymore. I mean, [3 Floyds co-founder] Nick Floyd wouldn’t do that. You just don’t see things like that. It’s nice to get a text from him every once in a while. I don’t know how many head brewers that do that.”

Just like at Map Room, the beer backed up the perusal connection at Twisted Spoke. Thompson brought the beer in before the medals even put them on the map—his interaction was with a small wine distributor that first brought Brickstone trickling into the market in those first bombers.

“He just brought a big bomber of beer with him, and he asked me to sample it out, and I did,” Thompsons says. “I think it was only the APA at the time. People liked it because West Coast IPAs were popular, kind of the extreme. But the APA was something that was milder. It wasn’t as highly carbonated. It was just easier to drink than some of the IPAs I think. When they won the gold medal, it did help sell more of it. Now we sell about a keg a week. It sells as fast as some of our faster movers, like Surly or Green Flash or Brooklyn Lager.”

So with some early placement success, and clear interest, Brickstone went looking for a bigger brewhouse and started taking the idea of becoming a production brewery seriously. “We were still considering a 7-barrel,” Vasilakis says. “We didn’t think we’d ever be able to sell that much beer. But Newlines refused to sell us a 7-barrel brewhouse because they knew we’d outgrow it. We got bigger tanks and thought we’d never be able to sell it all. But Chicago Beverage did, and it was all just the Pale Ale on draft. They said whatever we could produce, they’d sell—and they fulfilled that commitment.”

This humble, multi-generational brewpub was gearing up for a major new chapter. Something that would look very different than an elderly Greek couple handing over the keys of their restaurant to the family, which was the likely scenario just a few years prior. And it took some convincing. “My dad’s 71,” Giannakopoulos says. “Deciding to build the production brewery was a big step. We all work constantly, not taking anything for granted. We have five families we have to think of. If something goes wrong, it takes down five families.”

“Deciding to build the production brewery was a big step. We all work constantly, not taking anything for granted. We have five families we have to think of. If something goes wrong, it takes down five families.”

Across the street, visible in a short distance, a brand-new production facility rises from the dust and short grasses of an undeveloped plot between car dealerships and shopping centers. It mimics the brown and cream colors of other developments further in the distance, but inside the view is much different—brand new concrete and steel.

“This area is really loyal. When we started expanding, it was important to us to stay in Bourbonnais,” Vasilakis says. “We didn’t want people to see it being canned in a different town. Because the community here helped us grow from day one, and the city support was huge.”

For their help developing the industrial park, the city was willing to give them the land at no cost. In fact, Brickstone became the first tenant. And it’s so new, they still haven’t hung a sign on the door. You can sense the anxiety that still lingers from the decision to grow. “I’d say at 20,000 barrels we’ll be set,” Vasilakis says with a hopeful tone. “We’re happy with where we’re at right now. As a team we decided we didn’t want to keep expanding and lose control of it. You look at trending numbers, and they go up and down, and you think differently. A lot of it’s psychological.”

After holding back and being patient for so long, the pent-up energy of the business seems to have enough runway—for now.

“I’d love for Illinois to drink all that,” Vasilakis says. “We’re in about 40% of the state right now. Very little in Champaign, Springfield, Bloomington. We don’t even get to Rockford. So we know the growth is there. And most of it’s with the Miller Cluster—90% of our beer is with 5-6 distributor houses. But we still like making our own sales calls. We don’t want to lose that. ”

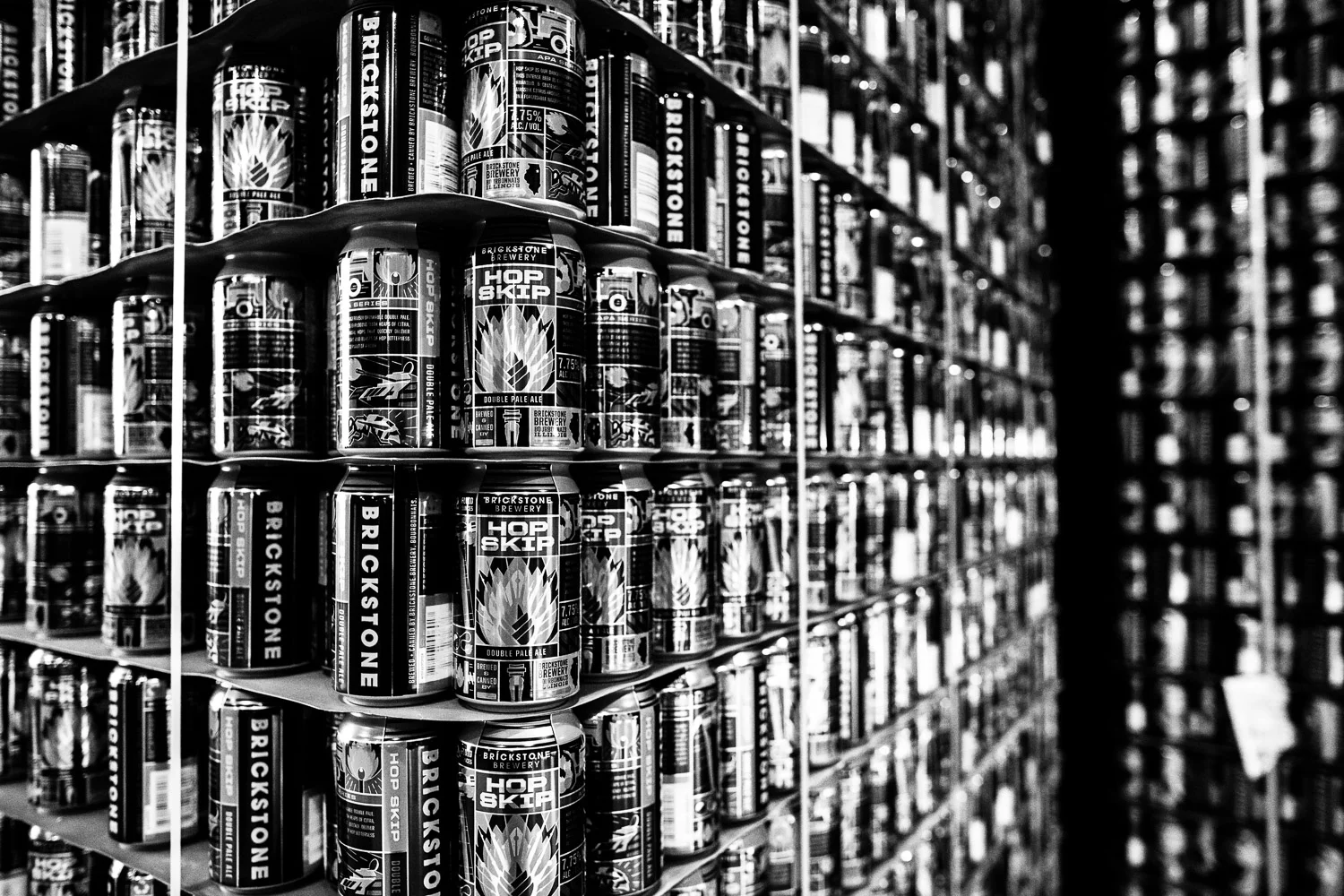

In stark contrast to the warren of tanks and narrow passages in the restaurant, in the new space, pallet after pallet of 12-ounce cans rise toward the ceiling. And they’re only on their third beer. They started with the tip of their spear, the American Pale Ale, an airy, well-balanced and generous melange of Amarillo, Citra, and Centennial over the course of five additions. It was followed most recently by Hop Skip, a Double Pale Ale, a simple elevation of the base Pale Ale recipe. The two beers are remarkably similar, evoking the subtle tweaks that a European brewer might make to a recipe over time in the pursuit of diversity for their customers, but also simplicity and perfection in the brewhouse.

“Anyone can brew an IPA,” Vasilakis says. “It does’t mean that the more bitter, the better. So we took our flagship and made it a little bit stronger with more hop character. But we didn’t want it to be more bitter. Then it wouldn’t be based on a Pale Ale anymore.”

For their part, the Binny’s retail store chain has adapted to Brickstone’s growth, and is happy to finally have an influx of Brickstone beer. “In the beginning, we told them we’d sell whatever we can get for now,” Binny’s spirits and beer specialist Pat Brophy says. “And if we run out after a week, we run out. If you get us more, you get us more. And we’d do our best to wait patiently for cans.”

But now that they’re getting a steady supply of the APA and others, the commitment continues. “We went all in on it,” Binny’s assistant beer buyer Kyle Fornek reiterates. “A little over a year ago when they launched in cans, Pale Ale and Hop Skip, we were all in. Bought as much as we could and sold as much as we could. Still doing the same thing.”

It’s been a hesitant, thoughtful step out from the APA as they expand the portfolio this time around. “In the beginning, they released the shandy a little late,” Brophy says. “Didn’t do very well. The APA flew. And the Belgo version of the APA did really well when it came out. But if it wasn’t the hoppy stuff, it kinda sat around. They were brewing a couple of styles that weren’t conducive to bombers. Like you don’t really put a shandy in a bomber and expect it to do much. But we wanted to support them as a brand, not just as the APA brewery, so we’d put these on the shelves and see how they’d do.”

These days, the plays are making more sense.

“The APA sells the best,” Brophy says. “The Hop Skip sells almost as good, and then they just released a Witbier a couple months ago. It’s a Wit, it does all right. There’s not really witbiers outside of Blue Moon that set the sales world on fire.”

Aside from the scale and financial risk of the production brewery, entering the packaged beer game is no small matter. Managing the tightening resources for cans, setting up and running the line, and attaining a decent shelf stability for a heavily aroma-hopped beer isn’t for amateurs. And it could sink a brewery, even one with two medals, turning them into weights around their necks instead.

“Packaged beer is whole different monster,” Vasilakis says. “We didn’t have experience in it. Kegs are so much easier from a quality standpoint. We knew it’d sell through quickly, which helps. At the time, we weren’t dropping 20 cases at a time, but we do that plenty now. Winning a medal can be good and bad. It makes people want to try it. But it also means people have big expectations. You get more criticisms when you get on that pedestal.”

The same obsessive approach to perfecting the beer for the medals is now paying off in their pursuit of a quality packaged product. “We have a dissolved oxygen meter,” Vasilakis says. “And even in the last nine months, we’ve made a lot of advances and gotten more comfortable.”

The team also makes frequent visits down the street at Crown where the cans themselves are printed. With its current equipment, Crown can make 5.5 million cans a day, Vasilakis says. And before craft beer became so diversified, that was an incredibly efficient process. “Now the changeovers are tough on them,” he says. “To get set up and get the colors right for all these different brands can take time. But once it’s running right, we’re done with our entire run in 10 minutes.”

Entering the market with a second beer that uses the same sought-after hop profile of Citra and Amarillo is also risky. Both hops are in high demand, and the trading boards amongst brewers are constantly lit up with those names. And we’re not talking about buying extra hamburgers for the brewpub. We’re talking about massive hop contracts for a family of seven to get behind. The shift in scale is immense, even at the batch level.

“Our first order of Citra hops was 88 pounds and I didn’t think we’d be able to go through it all,” Vasilakis remembers. “Now, a single dry-hop is 220 pounds. I bet there’s over 350 pounds in a complete batch of Hop Skip right now.”

“We went from a little place where we thought $30-$40,000 of hops was a big deal. And now we’re contracting millions of dollars worth of hops.”

And like their canning runs, securing the future of those hops is paramount to their current trajectory of success. “We took a big gamble contracting a lot of hops—up through 2020,” Vasilakis says, his eyes visibly widening at the thought of it. “We all sat own at the table together and thought, ‘Wow.’ We went from a little place where we thought $30-$40,000 of hops was a big deal. And now we’re contracting millions of dollars worth of hops. What if this expansion project was late or didn’t do well? We sat down with the team for a good year before we got agreement. I made sure every single family member agreed. I didn’t want anyone asking me why we had two million dollars of Citra hops on the way.”

Now that they’re off and running with production, it’s fun to look back at what seemed like a distant future. “I think it was a big deal, man,” says Binny’s Fornek. “Hard-core beer guys like us try not to get too hung up on awards and packaging and stuff like that, but that was a big deal. As soon as they won that award there were people in our stores asking for that beer, and we were saying, ‘No, it’s only available on draft. Hopefully it’ll get packaged some day.’"