Used to be, beer was this or that—one style or another. Anymore, though, the in-between is becoming the everyday. Belgian IPAs, India Pale Lagers, and Imperial Milds are less known as interesting one-offs and more regularly considered part of a core lineup. So how does a brewery create something distinct in an ever-blurring landscape? Screw the rules and focus on flavor.

That’s what Nick Nunns and TRVE Brewing Co. are doing in Denver, one of the world’s most populated and competitive beer markets.

“We brew some beers really well to style," Nunns says. "Our Stout is a really great Stout. Our Farmhouse is a really great Farmhouse. But our Gose? It’s our interpretation. Our American Table Beer? Who knows what the fuck that is.”

That Table Beer, Hellion, would probably be classified as an American ESB. Probably.

“Hellion is the beer we make for us, and everyone else is just along for the ride," he says. "Technically, it fits within the ESB category. But it uses a bunch of American hops. It uses a shit-ton of oats to give it some heft. It’s kind of an ESB. It’s kind of an Amber. It’s kind of something else.”

That “something else” approach pervades TRVE, beer makers who self-describe as “style blasphemers and category agnostics.” They’re also a heavy metal brewery, which is a well-defined aesthetic in craft beer in these post-FFF times, but those nonconformist ideals have deep cultural roots that help distinguish them from other breweries in the rather straight-laced Denver scene.

Clad in all black, with a black beard and closely shaved head, Nunns is as careful with his words as he is his color scheme. What some might perceive as mild arrogance is more of a supreme self-awareness, a comfort in his own skin. He knows what he’s doing with TRVE is different—in both flavor and approach—than anyone else in the area.

“It’s not a conscious effort to set ourselves apart," he insists. "It’s just an inherent ramification of our mindset. It’s so ridiculously outdoors-y here, it’s almost infuriating. But I think that’s something that makes us different. We haven’t touched that lifestyle with a 10-foot stick. Everybody else can be the outdoors-y brewery, and we’ll just do what we want to do.”

Another distinction from their peers is TRVE's focus on restraint. That’s right, the skull-adorned, pentagram-plastered, Loki-channeling brewery, pumping the heaviest of the heavy rock 'n' roll through their taproom speakers at 100 decibels, wants to hone in on subtlety.

“We want to make sure nothing is overpowering any other character in the beer,” Nunns says.

It’s an exercise in balance, and the resulting nuances are the common thread running through TRVE’s wildly varied lineup. Roasty, light, crisp, tart, earthy. All in moderation and all with a counterpoint. This is no small task with offerings like MMXIV-IV, an utterly unique Imperial Gose that’s Brett-fermented in tequila barrels, or Grey Watcher, a beautiful and haunting kettle-soured Grisette that clocks in somewhere around 4%.

Sours, especially barrel-aged sours, have been a focus for the brewery since it opened in 2012. And they’ve put TRVE on the map in a big way.

“It’s been fucking bonkers," Nunns says. "From day one it’s been out of control. We were just running out of beer all the time. Every weekend, we’d be wiped out entirely. If we were lucky, we were open four days a week.”

It got to the point where they had to limit growler sales to club members only, just to keep things steady. But that was back when they were on a meager 3-barrel system at their taproom. Earlier in 2015, after about a year of planning, TRVE opened their brand-new, 10-barrel production facility, dubbed The Acid Temple. And though the name suggests the building is exclusively for sours, they’re transitioning production of their full lineup to the new space as well.

“We thought, ‘Why brew 3 barrels at the taproom when we could do 20 here?’" Nunns remembers. "So we’re shifting our plan a little bit to turn the Temple into our main production area, and have the Broadway location be what it really should be, which is a pilot system.”

Not only will this allow Nunns and his crew the ability to outpace demand at the bar and experiment along the way, it will give them enough surplus to start distributing throughout Denver.

“We’re sniffing butts with a few distributors right now," he says. "It just makes sense to find somebody who wants to build this up with us, and not run ourselves ragged self-distributing.”

And with the way they’ve built out The Acid Temple, they have plenty of room to expand. The 5,000-square-foot space is Spartan—patched drywall, exposed rafters, a completely raw floor. But it houses TRVE's 10-barrel brewhouse, a pair of 20-barrel fermenters, a 20-barrel brite tank, 8 puncheons for oaked primaries, and more than 50 wine and whiskey barrels for aging. Somehow, it still feels like acres of empty floor space remaining.

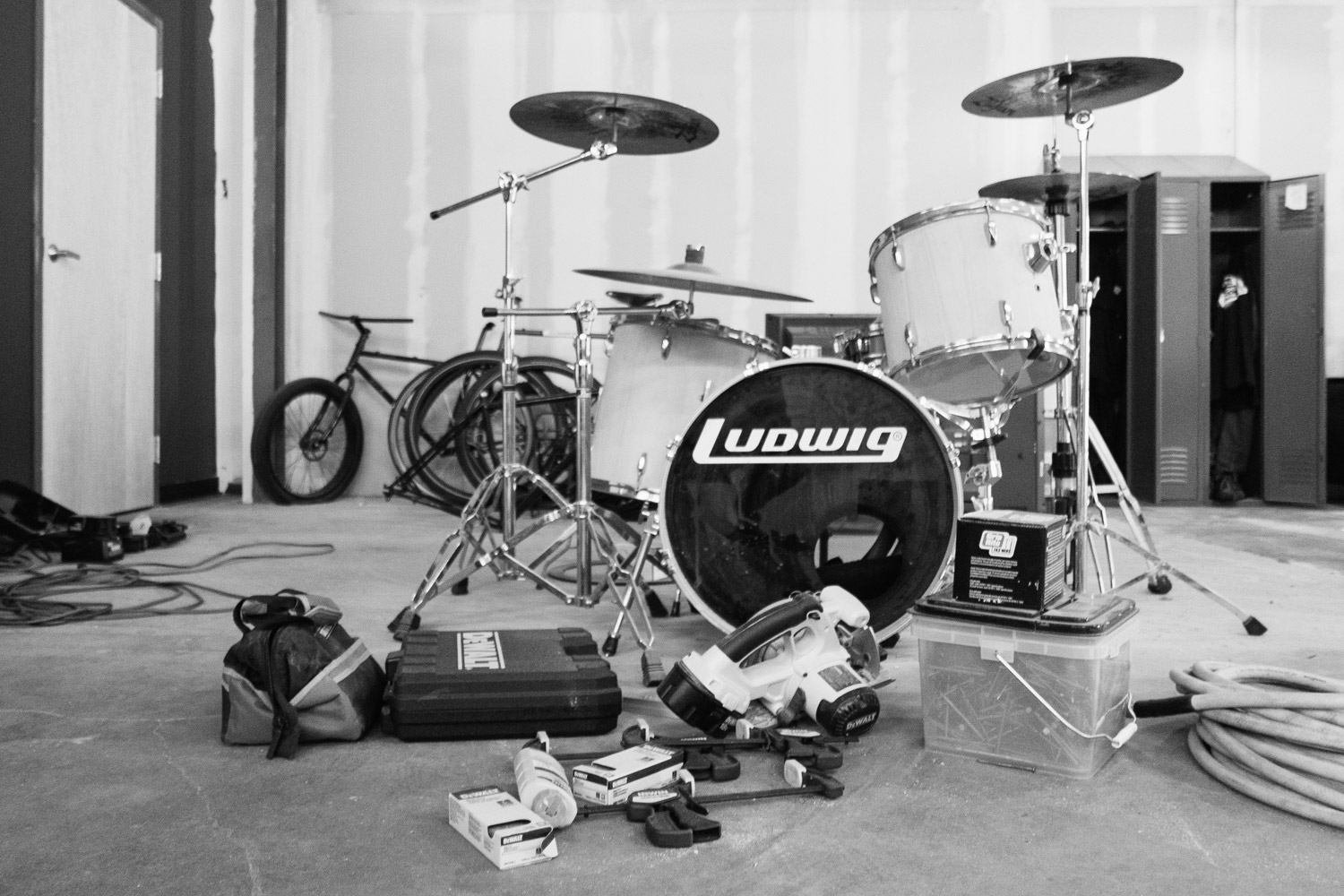

The other thing you’ll find at The Temple, amongst the tools and equipment being used to build out the cold storage, is a set of drums.

“The kit’s been collecting a lot of dust these days,” Nunns admits. “I don’t really have a lot of time anymore.”

Nevertheless, it serves as a reminder of the role music plays in the creative process of the brewery, and the brewery’s place in the Denver landscape. Nunns has a knack for describing beer in musical terms—deep, piercing, high-pitched, fast, slow, loud. His expressions become exaggerated and his voice jumps up a half-octave or so when he talks about it.

“All these things have different tonal ranges to them," he says. "Thinking about beer through music is just kind of how I wrap my head around flavor.”

This is the thought process that drives TRVE’s ethos. Whether you’re listening to grindcore or smooth jazz, music is all about harmony of disparate elements like rhythm, tempo, pitch, volume. It’s easy to see how that sort of approach, filtered through Nunns' mindset as a former electrical engineer, results in the delicate, carefully constructed balance of chaos and order when developing flavors.

That combination of disparate elements extends even to the people frequenting TRVE’s taproom in downtown Denver. The metal theme paired with the unexpected beer styles—or lack thereof—has resulted in a converse amalgam of bar patrons. The tatted-up, patched, pierced, and hirsute mingle with the Polo'd-out, clean-cut, and vanilla.

The metal crowd comes in for the vibe, and is exposed to a bevy of new flavors. The beer hunters show up, and are exposed to sounds they might not normally experience. The heavy and the light pony up to the bar, all the same. It’s a symbiotic relationship with TRVE at its center, resulting in fans from all walks. Nunns doesn’t take that for granted.

“I have a bunch of metal friends who didn’t even know what sour beer was until they came in," he says. "Now, they’re hooked. It’s just really cool to be able to open people’s eyes to what shit can be. That’s the job of craft brewers, to expose people to new things. To new beer. To better beer.”

Helping Nunns craft that better beer is a former-patron-turned-head-brewer, Zach Coleman.

“Zach started coming into the bar on day one," Nunns remembers. "He was a regular. We got to talking and we just knew that, eventually, he’d have to be part of we were doing here.”

Coleman joined TRVE in 2013 and made an immediate impact, brewing their first barrel-fermented beer, Eastern Candle, a Pale Wheat Bretta aged in white wine barrels.

“From that first beer, Zach’s done so much to bolster our reputation, and perfect the beers I laid the groundwork for," Nunns raves. "He’s really elevated all our flavors.”

Like Nunns, Coleman is also a drummer. That shared mindset goes a long way to creating a common language when they talk about flavor. Like good songwriting partners, the two seem to bring out the best in each other, enriching the final product in the process. And much like any great musician, Nunns is quick to cite those that influence him.

“Our whole sour program is because of Jason Yester at Trinity Brewing," he says. "No joke. He told us to try this, this, and this. We did, and were like, ‘Fuck, this is awesome.’ That’s what really set us on our path.”

But for as much as TRVE’s sour program is at the heart of what they do, Nunns is quick to caution that “sour beer is getting so hoity-toity these days. That’s something we’re really trying to rail against.” They want to keep the beers approachable while still testing the limits of what exactly sour means.

A technique they’re currently piloting at The Acid Temple involves primary fermentation with saison yeast inside puncheons, treating them almost as mini-foeders, but without any funk. Once primary fermentation is complete, they transfer the beer into the wine barrels and add Brett, and fruit. Montmorency cherries, for example.

The result is, not surprisingly, nuanced. The flavors meld together more, and create less distinction between the fruit’s contribution and the yeast’s. “It’s oak the whole way through, so you get a different profile than doing primary in stainless,” Nunns says.

The beer has a few more months left in barrels before it’ll be ready to serve, but early nail-pulls are encouraging. And if everything goes according to plan, the all-oak process will be one that’s used moving forward as TRVE starts to bottle more and more of its beer.

In addition to larger format, limited releases of their barrel-aged beers, Nunns and company are also looking to start packaging their stainless beers.

“We want to start bottling up some stuff in 4-packs, like the Grisette and the Gose, and get those out into the market," he says. "We’re just getting production ramped up and the recipes 100% dialed in.”

In doing so, TRVE will carve out an even larger footprint in the Denver area, and get their beer in front of more metalheads and discerning palates. They’ll continue to live in the gray stylistic area while staying true to their headbanger roots.

“The barriers between music genres are getting blurrier, similar to what we’re doing with our beer," Nunns says. "We’re taking these concepts and scooting them this way or that to see what happens. We’re coming up with end results that are new and interesting, because you wouldn’t think to put those things together.”

You know, just like metal and subtlety.